CARE ACTIVIST IN RESIDENCE WORKSHOP BY : DR. JAMES GOMEZ ( ASIA CENTRE )

Developing an advocacy strategy for Rohingya refugees in Southeast Asia

CARE-Activist in Residence-James Gomez-23Oct-Workshop

Mediasite Link for Live Streaming : CARE Activist In Residence :Workshop

Click on the url link for media related articles on Dr James Gomez

CARE OpEd: When She Spoke to “Ma’am” About Sexual Abuse By “Sir” She Was Deported

Sexual harassment, Domestic Work, and Infrastructures for Voices

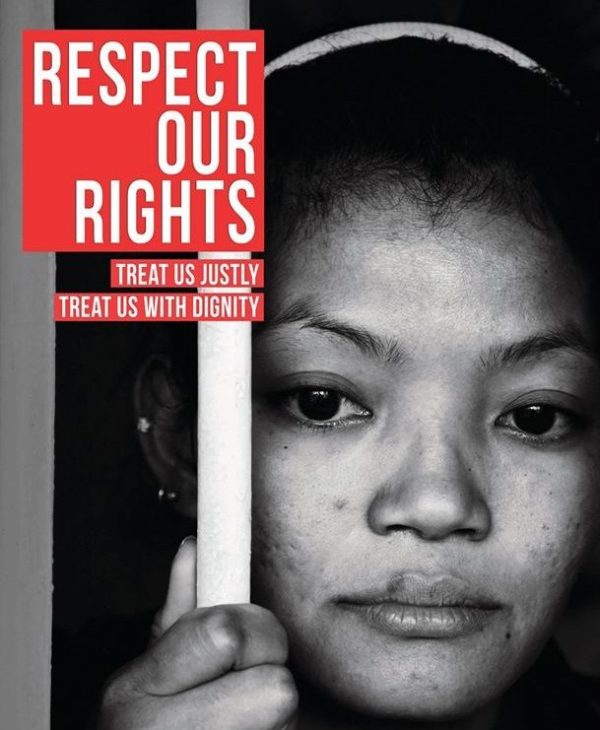

Between 2013 and 2018, the Center for Culture-Centered Approach to Research and Evaluation (CARE) ran the “Respect our Rights” campaign with foreign domestic workers in Singapore.

The campaign, driven by the voices of domestic workers, designed and carried out by domestic workers with support from our research and production teams at CARE, highlighted the plight of domestic workers within the confines of homes in Singapore. Grounded in the framework of creating infrastructures of communication that the women would own, the project sought to build anchors for addressing threatening workplace practices that poorly affect the health of domestic workers. Through outdoor advertising, television and print ads, mobile events, digital media campaign, documentary film, and a series of white papers drawn from our research conducted with domestic workers, the campaign drew attention to the various facets of exploitation and abuse in domestic work.

A consistent theme that appeared throughout our in-depth interviews and advocacy-based fieldwork was the sexual abuse that domestic workers experience while on work.

In many of these instances of experienced abuse, domestic workers discussed how the nature of domestic work meant that they did not have a place to go to and often did not know whom to speak with when experiencing the abuse.

The four walls of the home silenced the stories of sexual abuse. The tremendous power imbalances between employers and domestic workers and the absence of accessible mechanisms for addressing workplace grievances rendered pathways for communication invisible.

Consider the story of Sarah, a domestic worker who had travelled to Singapore from the Philippines so she could send her children in the Philippines to school.

For many days, she had been experiencing sexual abuse.

Her “Sir” [referring to the male employer in the household] would inappropriately touch her. When this harassment occurred the first time, she did not know how to react. She did not push back immediately because she was afraid that her employer would deport her to the Philippines if she spoke up.

As the incidences of abuse kept occurring, she made herself speak up, and forced her body to fight back, pushing away an unwelcome hand or a forced embrace.

The sexual abuse carried on, with the forms of abuse increasing in frequency and magnitude. As the abuse magnified, so did her sense of feeling unwell. Sarah would often throw up, experience stomach cramps, and breaking into uncontrollable tears at the end of the day when she went to bed.

It was nerve racking to anticipate the sexual abuse, to actually experience it, and then to respond back when it happened. She shared how she stayed up until late at night planning strategies of response, figuring out what she would do when her “Sir” touched her again.

It took Sarah all her energy to gather up her strength and speak about the abuse to her “mam.” Although she felt that her employer would not believe her, she needed to at least try to speak up as she “could not take it anymore.”

When finally Sarah spoke with her “mam,” she was accused of lying, of “making up” things to create trouble. Her “mam” threatened Sarah that she would call the immigration and checkpoint authorities in Singapore and get her deported.

The story of Sarah is also the story of Radha, Nithya, and Carla. Carla also shared a story of her friend who was deported, having been accused of stealing from the employer after having brought up the incidences of sexual abuse to the employer and having asked him to stop.

The tremendous power imbalances at work, the isolated nature of the work, the ambiguities around the norms of work and home in domestic work, and the invisibility of communication structures for voice translate into suffering through the everyday forms of sexual abuse. Domestic work is a case exemplar of precarious work, without policy protections, all the way from wages to working hours to workplace conditions.

Even as our advisory group of domestic workers created a digital space on Facebook for sharing their stories, stories of sexual abuse are often not shared here. The digital space feels insecure and threatening, especially with the threat of being deported looming on the horizon.

These stories voiced by domestic workers in Singapore resonate with stories voiced by domestic workers in India, with experiences of abuse that are often deeply immersed in silence. In our ongoing collaborative fieldwork with domestic workers in India, experiences of sexual abuse are tied to hierarchies of class and caste, perpetuating the silencing of women.

Popular culture depictions of relationships between domestic workers and employers (son of employer) render these forms of sexual abuse as normative, failing to approach domestic work from a framework of workplace policies and protections.

The nature of the workplace in domestic work perpetuates the oppressive and insecure working conditions. What is a place of work for a domestic worker is the home of a family, typically positioned much higher in the social power structure. The absence of workplace policies that govern the home as a workplace means that workplace communication channels are mostly absent and even if structures outside the workplace are indeed available (Ministry of Manpower in Singapore), the women don’t know how to access these structures.

While advocacy campaigns such as the “Respect our Rights” campaign push for better workplace policies for domestic workers, for domestic workers to have a voice, opportunities for collective bargaining are fundamental. The International Labour Organization (ILO) emphasizes that it is important for domestic workers to “first be recognized as workers in the labour law, to enjoy fully the right to organize and collective bargaining, and to be registered trade unions.”

In countries such as Uruguay, Brazil, Bolivia and South Africa, domestic workers are unionized in large numbers. Closer, in Hong Kong, domestic workers organize by nationality, and then come together under the Federation of Asian Domestic Workers Unions (FADWU). These union frameworks are integral to domestic workers having a voice and through their voice, transforming the workplace conditions that threaten their health and wellbeing.

The #MeToo campaign across India has drawn attention to the nature of sexual abuse in workplaces. In the confines of homes as workplaces, domestic workers often face a wide array of sexual abuse which are normalized into the cultural fabric that organizes home spaces. It is time Indians turned to the sexual abuse of domestic workers that is written into the cultural fabric and is simultaneously erased.

by : MOHAN DUTTA & SATVEER KAUR | 11 OCTOBER, 2018

The Center for Culture-Centered Approach to Research and Evaluation (CARE) carries out advocacy projects through collaborations with workers in precarious working conditions across the globe. Mohan J. Dutta is the Director of CARE and Satveer Kaur, Lecturer in the Chua Thian Poh Community Leadership Center, serves as a researcher on the project. The latest manuscript highlighting the struggles of precarity of unskilled migrant work in Singapore is published in the International Journal of Communication.

Article Source: https://www.thecitizen.in/index.php/en/NewsDetail/index/7/15226/When-She-Spoke-to-Maam-About-Sexual-Abuse-By-Sir-She-Was-Deported

Image source: http://www.fas.nus.edu.sg/srn/archives/53554

CARE: ACTIVIST-IN RESIDENCE PROGRAM- Dr. James Gomez (ASIA CENTRE)

CARE is delighted to share our upcoming collaboration with Activist-In-Residence: Dr. James Gomez. He will collaborate with CARE on Communication, Democracy, and Freedom in Asia, highlighting the ‘Fake News’ challenge to democracy and co-produce a CARE White Paper with Prof. Mohan Dutta during his residency.

Dr. James Gomez is the Chair, Board of Directors of Asia Centre, a not-for-profit organisation that seeks to create human rights impact in the South-east Asia region. Dr. James will be presenting on ‘Fake News’ and it’s impact on democracy. During his time with CARE, as an activist he will deliver a public talk, conduct a workshop on a method of social change communication, and collaborate with the CARE team on developing a white paper. Dr. Gomez currently oversees its operations in both Thailand and Malaysia and is leading the partnerships for the Centre’s many activities in other parts of the region.

Dr. James Gomez brings to Asia Centre over 25 years of international and regional experience in leadership roles at universities, think-tanks, inter-governmental agencies and non- governmental organisations. He is the convener of Asia Centre’s upcoming international conference on Fake News and Elections in Asia, 10-12 July, Bangkok, Thailand.

KEY EVENT DATES:

23rd – WORKSHOP: Developing an advocacy strategy for Rohingya refugees in Southeast Asia.

24th – PUBLIC TALK: Fake News, Digital Democracy and State Repression

25th – CARE RECEPTION

26th – WHITE PAPER LAUNCH:

Please RSVP here for more information on these events.

Click on the url link for media related articles on Dr James Gomez

Sue Bradford takes up residence as Massey University’s activist at CARE

“Activists and academics are not typical bedfellows, but Sue Bradford is making sure the two parties can learn from each other.

The well-known activist and former Green Party MP is the activist in residence at Massey University in Palmerston North for a week. Bradford was asked about a month ago by professor Mohan Dutta, who is the dean’s chair of communication for the new Centre for Culture-Centred Approach to Research and Evaluation, to take the position.

The two are producing a paper on the partnership between academics and activists in struggles of the oppressed. Universities often have an artist in residence, but having an activist is not as common. “This question around the relationship between people who are active outside in grassroots organisations and how people inside the universities can work together is quite fraught and difficult because there are often problems,” Bradford said. “But there are also huge advantages to both. It has never been an easy path in this country.”

She said this week was an opportunity to explore the relationship between activists and academics.”Often, academics are seen as people that come in and do research on us, do their PhDs on us.” She wasn’t given any instruction about what she could do while being the activist in residence. Bradford said there wasn’t the same level of political activity in this generation of students as there had been in the past.

On Wednesday, she spoke to students about her background in the 1980s and 1990s working with an unemployment workers group and unions, and on Thursday she held a workshop with Manawatū activists and students. At 2pm on Friday she is speaking about social movements and her history in and out of Parliament, having previously been an MP for 10 years.

“It’s a completely new experience but at the same time I’m into new experiences and finding out about new people.”

Bradford said the CARE centre worked on transforming structures through communication, culture and community, and that’s what she had spent her life doing, so was keen to be involved. Bradford works for the Kotare Trust in Auckland, which does research in education for social change in Aotearoa.

Dutta brought the CARE centre with him to Massey from the National University of Singapore and he is a leading scholar for health communication and is a researcher of indigenous rights and activism. He said the work of CARE was about creating communication platforms for democratic spaces so communities in disenfranchised places had a voice. The centre also looks at poverty and health for migrants and refugees.”

Article Source: www.stuff.co.nz

Article Link: https://www.stuff.co.nz/manawatu-standard/news/107443172/sue-bradford-takes-up-residence-as-massey-universitys-activist

Click on the url link for media related articles on Sue Bradford

CARE Activist in Residence: Public Talk by Dr. Sue Bradford- Live Streaming

Wednesday 3rd OCTOBER, 2018, 1.00 pm – 2.00 pm

Public Talk: SOCIAL MOVEMENTS, PARTY POLITICS, AND STRUCTURAL TRANSFORMATION: NAVIGATING A PATH FORWARD IN CHALLENGING TIMES

GLB3.08 | Geography Building, Manawatu campus | MBS1.42 Massey Business School Seminar Room, Auckland campus | 5D12 Communication Lab, Wellington campus

Mediasite: https://webcast.massey.ac.nz/Mediasite/Play/491fa9258f244193a9172fb0fefc9f9c1d

Please click on the URL link for more media related articles on Sue Bradford

CARE WHITE PAPER LAUNCH- ACADEMIC-ACTIVIST PARTNERSHIPS IN STRUGGLES OF THE OPPRESSED

CARE WORKSHOP-FROM GRASSROOTS ORGANISING TO POLICY ADVOCACY: THE TRAJECTORY OF SOCIAL CHANGE

Public Talk by Dr. Sue Bradford: Activist-in-Residence at CARE

Activist-in-Residence at CARE: A collaboration with Dr. Sue Bradford

CARE is delighted to share our upcoming inaugural collaboration with activist-in-residence Dr. Sue Bradford at Massey University. She will collaborate with CARE on re-imagining academic-activist linkages and co-produce a white paper with Prof. Mohan Dutta during her residency.

Dr. Bradford has a lifelong background in street and community activism, and is a mother of five. Much of her work has been in unemployed workers’ and beneficiaries’ organisations. She was a Green Member of Parliament for ten years (1999-2009) before going on to undertake a PhD in public policy with Marilyn Waring at AUT, graduating in 2014.

During her time with CARE, as an activist she will deliver a public talk, conduct a workshop on a method of social change communication, and collaborate with the CARE team on developing a white paper.

Dr. Bradford has a particular interest in the interface between radical community development, activism and the role of academics and universities. She is always searching for ways in which these spaces can be more productively navigated than is often the case.

She currently works for Kotare Research and Education for Social Change in Aotearoa Trust as well as picking up various speaking and writing engagements.

For more media articles on Sue Bradford click on the url link

For more event details follow us on