CARE Op-Ed: The role of communication in addressing Māori health disparities: An appeal for voice by Prof. Mohan Dutta & Dr.Steve Elers

The role of communication in addressing Māori health disparities: An appeal for voice

The Māori Affairs Select Committee on Māori health inequalities point to the entrenched disparities in health outcomes for Māori compared to Pākehā, highlighting the importance of examining and understanding the sources of these inequalities.

The sources of inequalities in outcomes in health and wellbeing is also the subject of the hearings of the Waitangi Tribunal, drawing on presentations that point to systemic structural racism that impact the experiences of Māori in the health system.

These inequalities in experiences of and with health and care are communicative, tied to the nature of interactions in health settings and in the various ways in which racism shapes these interactions.

In our research with the culture-centred approach to health and communication, we attend to the question of voice in the realm of unequal health outcomes. We suggest that the erasure of Māori voices in health interactions and in how the health system is constructed is integral to the perpetuation of inequalities.

Our approach therefore invites voices of those at the margins of society, voices that have been historically erased, as anchors for addressing the entrenched health inequalities.

We are honoured to be hosting Tāme Iti of Ngāi Tūhoe as our next activist-in-residence, and we will work with him in understanding this question of voice. His intervention from the Māori proverb “kanohi ki te kanohi” [dealing with it face-to-face] is a powerful solution to the marginalisation of Māori in health systems. Making the spaces for Māori voices to be heard in health systems and in spaces where knowledge is produced is a critical starting point for addressing inequalities in health and wellbeing outcomes.

When such voices from the margins of New Zealand society speak, they are meant to disrupt the unequal structures. The very act of speaking is meant to disrupt because it is only through disruption of powerful structures that erase voice can opportunities for solving inequalities be created.

Because for those in entrenched positions of power, voice is threatening, an invitation to voice is a direct challenge to the organising categories of power.

That within Universities and within mainstream structures of society a certain cross-section feels threatened with the voice of Tāme Iti speaking is a reflection of the communicative inequalities that constitute colonial structures. Under the guise of civility and appropriate conduct, voices that challenge the status quo and its inherently racist logics are strategically and systematically silenced. So for many of the free speech advocates within colonial structures, the right of an indigenous voice to speak can be sacrificed under the pretext of appropriate speech.

It is however in this very space of voice that interventions need to be made if inequalities in outcomes of health and wellbeing are to be addressed.

Professor Mohan Dutta

Director of Centre for Culture-Centred Approach to Research and Evaluation (CARE)

and

Dean’s Chair of Communication, School of Communication, Journalism and Marketing

Massey University

Dr Steve Elers

Senior Lecturer

School of Communication, Journalism and Marketing

Massey University

The Islamophobia Industry and the Christchurch Terror Attack: A Call to Dismantle Hate

The Islamophobia industry is big business.

The shootings carried out by right wing White extremists in Christchurch are part of a global network of racist terror that are often legitimized, sponsored, and reproduced by the structures of the state.

The manifesto crafted by one of the White terrorists who carried out the terror makes reference to the U.S. President Donald Trump and draws on the hate propaganda that is a key element of U.S. public relations.

Islamophobia, the fear of the Muslim, is strategically manufactured through various forms of messages of hatred, legitimized and reproduced by the media, and manipulated by parties toward political gains.

The globalization of the Islamophobia industry

The Islamophobia industry is big business. The New Zealand shootings depict the wide reach of the industry and its global appeal.

From the transnational corporations feeding the “war on terror” to the digital media industries that profit from selling the hatred of Muslims to think tanks that are set up to cultivate strategically the fear of the Muslim, Islamophobia generates ratings, advertising dollars, and new markets for products of hatred.

Although projected as the work of the fringe right, the power of Islamophobia lies in seeding the hatred for Islam as a mainstream phenomenon, as a part and parcel of everyday civil discourse.

Digital platforms such as Swarajya Mag in India, and Centers such as the Center for Security Policy in the U.S. are established with the sole purpose of making mainstream the hatred for Islam through the circulation of the image of the Muslim invader that is antithetical to the ideas of civilization.

Propaganda narratives from U.S. to India

The narrative of the “civilization in threat” is strategically disseminated across spaces to seed and amplify Islamophobia. The manifesto circulated by the White supremacist terrorist in New Zealand is essentially anchored in the rhetoric of “White genocide.”

In the U.S., groups such as ACT for America led by Brigette Gabriel organize communities at the grassroots around the hatred for Islam, manufacturing the threat of the Muslim “other.” Setting up false narratives such as the “threat of Sharia law,” with over 750,000 members across the U.S., the organization positions itself as a national security organization, drawing up accounts of unwed Muslim migrant and refugee men who threaten White civilizational purity. Brigette Gabriel draws out links between the influx of Muslim refugees and the threat of rape, manufacturing the basis for the threat of “White genocide.”

In the White terrorist manifesto in New Zealand, the propaganda of “White genocide” is set up by comparing the fertility rates of White Europeans with fertility rates of communities of colour.

The global seduction of the narrative of Islamic rape culture is well evident in India in the Hindutva propaganda machinery.

The “love jihaad” narrative similarly manufactures a false account of Islamic rape culture, positioning Muslims as threatening the purity of Hindu culture. The narrative of Hindu genocide becomes the basis for manufacturing and circulating the threat of the Islamic invader, then being mobilized by the Hindutva forces in India to carry out systematic acts of violence.

The Zionist propaganda machinery produces the image and narrative of the Muslim other to silence any critique of its settler colonialism, occupation and apartheid policies toward Palestinians. A large proportion of the funding of the Islamophobia industry comes from Zionist organizations.

Islamophobic responses in India

The Islamophobia that is rampant in India prompts a cross-section of Hindutva forces to celebrate the attacks on the mosques in Christchurch.

For these Hindutva forces, the attack on the mosques is the appropriate and necessary response to the manufactured thread of Islamic terror.

Heuristically driven and devoid of evidence, these jubilations of the attack on the Muslims entirely miss out that the manifesto called for removing all coloured people (including Indians of all faiths) from what the terrorist articulation framed as White lands (of course ignoring the claims to land in New Zealand held by indigenous Maori). People of colour bear the burden of racisms that generate from White supremacy; Muslims bear this burden as attacks on their ethnicity as well amplified by the demonization of their faith.

The celebration of violence by Hindutva terror, although somewhat different in its framing and targeting of the other from the White supremacist terror, is a replica of White supremacist terror in its strategic deployment of violence to target Muslim minorities. Since 2015, at least 44 Muslims have been killed in India by cow vigilantes, driven by the narrative of civilizational threat.

For a global civilizational response

That terror has no place in civilized societies is the message that ought to form the basis for global response. In her bold and powerful speech following the terrorist attack, the Prime Minister of New Zealand Jacinda Ardern issued this clarion call for zero tolerance of hatred by stating that the haters have no place in New Zealand society.

Across the globe, the fabrics of civilized secular societies are threatened by the politics of hate and fear mongering, legitimized through political parties and electoral processes. These political parties that operate on the circulation of hate need to be targeted strategically and their machineries of hate dismantled.

The global machine of Islamophobia ought to be dismantled by a civilizational narrative of love, understanding and dialogue, with the fundamental commitment to fostering spaces for diverse voices, peoples, worldviews and faith traditions.

In India, dismantling the hate apparatuses of the RSS and BJP are the urgent calls of the hour. In civilized societies such as in New Zealand and Singapore, diaspora groups that operate on the circulation of hate have no place. Identifying, categorizing and dismantling such groups is as important as it is to opening up calls for dialogue.

Hate, White supremacist hate and Hindu hate need to be stopped before they consume the discursive spheres of civilized societies.

Mohan J Dutta is Dean’s Chair Professor of Communication at Massey University, University of New Zealand. He is the Director of the Center for Culture-Centered Approach to Research and Evaluation (CARE), developing culturally-centered, community-based projects of social change, advocacy, and activism that articulate health as a human right.

Article Source: www.thecitizen.in

Image source: https://thenewdaily.com.au/news/world/2019/03/16/jacinda-ardern-christchurch/

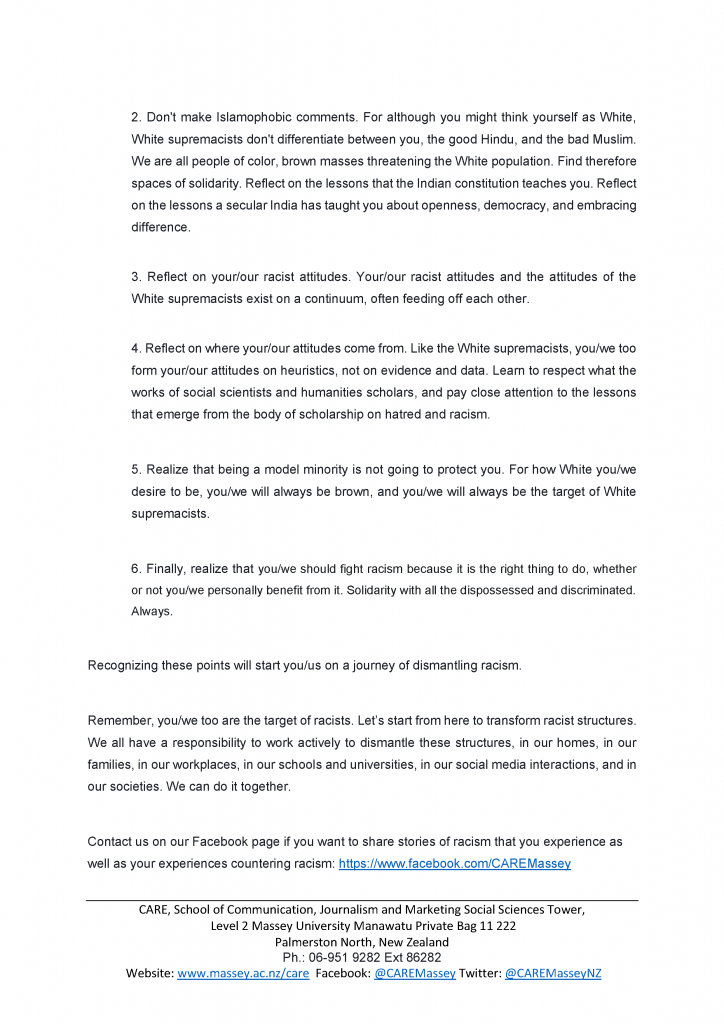

CARE Public Talk by Prof. Shiv Ganesh from University of Texas at Austin

Prof. Shiv Ganesh, from University of Texas at Austin , will be presenting a talk at CARE: Center for Culture-Centered Approach to Research and Evaluation on –

Potentials and pitfalls of Microinterventions as an engaged ethnographic method

Monday 11,March 2019

12 noon – 1 pm

GLB1.14, Geography building, Manawatu Campus

Vided Linked to Auckland : AT4 & Wellington: 5C17

Mediasite live stream : https://webcast.massey.ac.nz/Mediasite/Play/4a2ab793db7d448eb2f327272542a2ad1d

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/CAREMassey/videos/542751926233393/

Microinterventions—situated, small-scale, issue-based action in the context of long term ethnographic engagement—have considerable potential to enrich the quality of ethnographic research, and they can constitute an ethically responsive form of community-based research. Conversely, they can play into broader and vastly problematic narratives of researchers as imperial saviors, alienate communities from outsiders, and result in the continuing marginalization of already vulnerable groups. In this conversation, I discuss how one might consider the ethical imperative of engaging in microinterventions against the pitfalls of doing so, in the context of an ongoing field work project amongst Jenu Koruba tribal communities in Bandipur district and its environs in Southern India.

CARE Activist-In-Residence in News: Stuff -‘Activist Tāme Iti to take up residence at Massey’

Activist Tāme Iti to take up residence at Massey

Well-known Māori activist Tāme Iti will be Massey University’s next activist in residence.

He will be on the Palmerston North campus from March 18 to 22 as the activist in residence, a programme where an activist shares ideas with academic staff.

The purpose of the programme is to generate knowledge and an activist brings in different experiences.

The theme of Iti’s residency is “decolonising ourselves – indigenising the university”. He will hold a public talk, workshop, and release a paper. All events are open to the public.

Iti will be hosted by the Centre for Culture-Centred Approach to Research and Evaluation, which is a research centre within the school of communication, journalism and marketing, and the Massey business school.

Professor Mohan Dutta, director of the centre and dean’s chair of communication, said Iti’s residency would empower the voices of the marginalised.

“Tāme’s knowledge and expertise provide key theoretical anchors for us to critically engage and interrogate colonisation and racism, and the structural conditions that reproduce inequality,” Dutta said.

He said this semester the centre was exploring inequality in health and wellbeing.

“Tāme’s name came up because of his work in communication opportunities and opportunities of voicing particular claims and how those will translate into inequality in outcomes, and in health and well being.”

As part of the theme, Tāme Iti said it was important to “know your enemy – hongi hongia te whewheia”.

“The enemy out there, and the enemy internally – in ourselves,” he said.

The centre hosts a different activist in residence each month.

Activist and former Green Party MP Sue Bradford was the first activist in residence in October.

Bradford worked with Dutta on a paper about the partnership between academics and activists in struggles of the oppressed.

Dutta brought the centre with him to Massey from the National University of Singapore. He is a leading scholar for health communication and is a researcher of indigenous rights and activism.

READ MORE: Sue Bradford takes up residence as Massey University’s activist

Source: Stuff Limited

Article & Image Source: https://www.stuff.co.nz/manawatu-standard/news/111056676/activist-tme-iti-to-take-up-residence-at-massey

Maori Television -“iti-become-Masseys-Activist-Residence”

iti-become-Masseys-activist-residence

The CARE center (Culture-Centered Approach to Research and Evaluation) situated in the School of Communication at Massey’s Palmerston North campus hosts a different activist in-residence every month. From 18–22 March, Tūhoe elder and Māori activist, Tame Iti, will take up the role.

‘Decolonising Ourselves – Indigenising the University’ is the theme for Iti’s placement which will include workshops, a public talk and the release of a white paper.

Professor Mohan Dutta, Director of CARE says what Iti has to offer through his placement will assist in “empowering the voices of the marginalised as anchors to social transformation”.

“Tame’s knowledge and expertise provide key theoretical anchors for us to critically engage and interrogate colonisation and racism and the structural conditions that reproduce inequality,” says Dutta.

Iti says that it is important to “Know your enemy – hongi hongia te whewheia”.

“The enemy out there, and the enemy internally – in ourselves,” says Iti.

For more information including dates/times and venues please refer to the CARE website

All the events are open to the public and the public talk will be live streamed on Facebook.

CARE’s Activist-In-Residence: Tāme Iti on Radio WaateaNews

Iti shares vision as activist in residence with WaateaNews.com

Tūhoe provocateur Tame Iti is to give his views on how to decolonise yourself to students and the public at Massey University’s CARE center, also known as the Culture-Centered Approach to Research and Evaluation.

The centre at the university’s Palmerston North campus hosts a different activist in residence every month for talks and workshops.

Director Mohan Dutta says his knowledge and experience provide a way for students to critically engage and interrogate colonisation and racism and the structural conditions that reproduce inequality,

Mr Iti will draw on the whakatauki hongi hongiā te whewheiā, know your enemy, and ask whether the enemy is in ourselves.

He says everyone is colonised.

“But the way we are indigenised where we are today is really important. There needs to be some recognition and respect to tangata whenua. We are not trying to ditch that culture. We are saying here we are so how can we work together as a collective, the people living in this country, Pākehā are not the only other people who are here these days, the whole world is here now,” Mr Iti says.

Tame Iti will give a public talk at Massey University at noon on March 20.

Source: https://www.waateanews.com/waateanews?story_id=MjEyNDQ

CARE Activist In Residence – Tāme Iti

We at CARE are honoured that Tāme Iti will be CARE’s Activist-in-Residence from the 18th to the 22nd of March 2019.

Tāme’s upcoming visit comes just weeks after the United Nations Human Rights Council (2019) report reminded us of the following:

- “The impacts of colonisation continued to be felt, through entrenched structural racism and poorer outcomes for Māori” (p. 2)

- “Māori life expectancy was lower and unemployment rates were higher” (p. 3)

- “inequalities within the system and mental health outcomes, especially for Māori” (p. 4)

- “Māori were disproportionately represented at every stage of the criminal justice system, as both offenders and victims” (p. 4)

Tāme Iti is an actiivist-of-activists, bringing his art and activism together in decolonizing structures. His activism as performance offers many openings for imagining the role of communication in social cange.

Accordingly, this calls for a decolonising project to critically engage and interrogate the structural conditions that reproduce racism and poorer outcomes for Māori. Tāme Iti’s Activist Residency will interrupt the dominant discursive positioning and practices of Pākehā hegemony and will situate the university as a site of resistance to enable new ways in which we understand and conceptualise structural racism. We welcome Tāme Iti as our Activist-in-Residence. “Tēnā koe e te Rangatira. Nau mai, haere mai!” [Trans: “Greetings leader/chief. Welcome!”

RSVP to events : https://masseybusiness.asia.qualtrics.com/jfe/form/SV_8ofiQk2Yow6EDBj

Follow us on Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/CAREMassey/

Click on the url link for more related articles on Tāme Iti

CARE Academic Freedom Study

CARE Academic Freedom Study

CARE invites academics to participate in its ongoing study of academic freedom.

Would you like to share your experience with academic freedom at your institution?

In an ongoing study on “Faculty perceptions of academic freedom globally,” CARE is collecting narratives and experiences of faculty across the globe with academic freedom, seeking to identify the challenges to academic freedom as well as the potential solutions to it. The resulting report will form the basis of advocacy work carried out by CARE.

Please Note: The interview will be recorded and will take between 60 and 90 minutes, conducted over Skype. Your responses will be anonymized. The recording will be destroyed after the transcription of the interview.

RSVP your details below for the CARE Academic Freedom Study to register your interest and to receive further communication regarding the study.

RSVP Link: CARE Academic Freedom Study

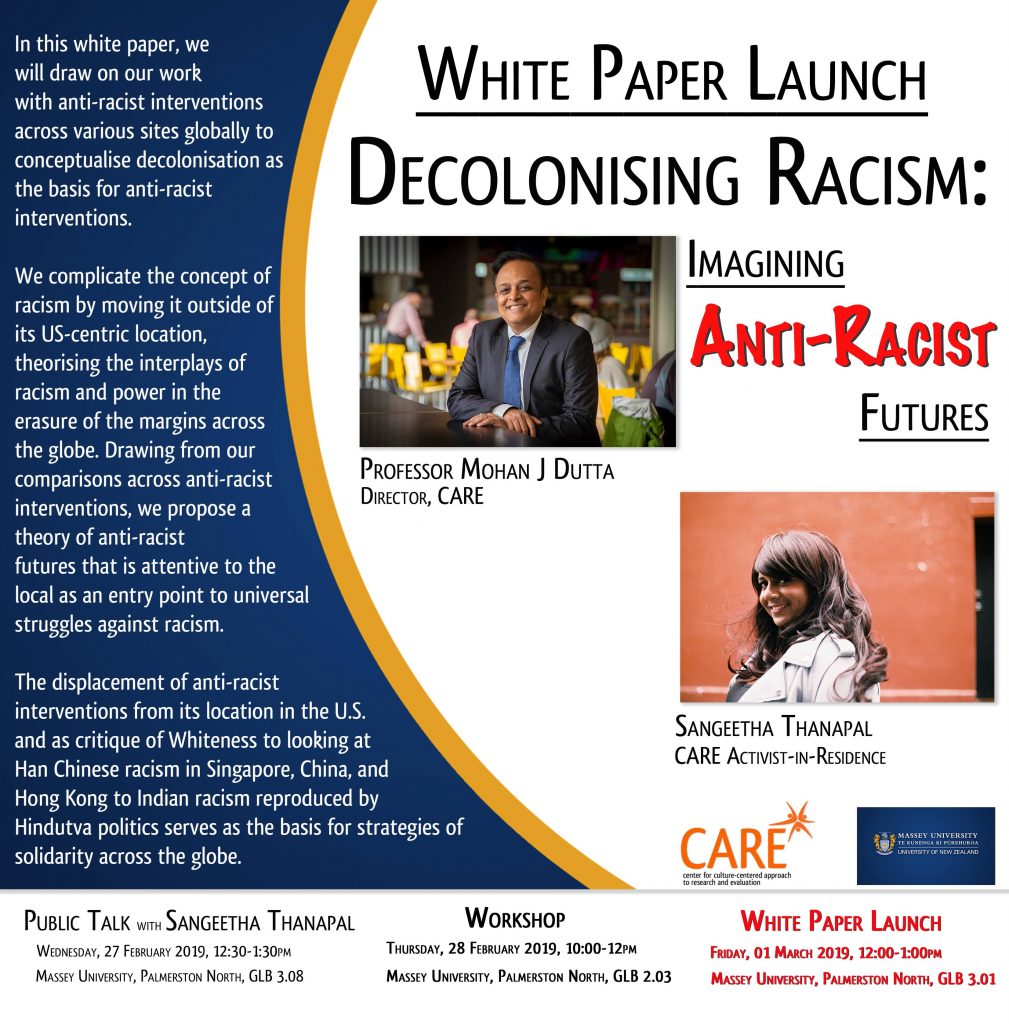

CARE Activist In Residence WhitePaperLaunch by Sangeetha Thanapal & Mohan Dutta

CARE Activist In Residence White Paper Launch:

Topic: Decolonising Racism: Imagining Anti-Racist futures by Mohan Dutta & Sangeetha Thanapal

1st March 2019 from 12.00- 100

GLB3.01 Geography Building

Manawatu campus Massey University

All Welcome. Free Event

#AntiRacistInterventaions #CAREMassey #CAREActivistInResidence

#MasseyCJM #MasseyUni #CAREMassey

Website:

https://www.facebook.com/CAREMassey/