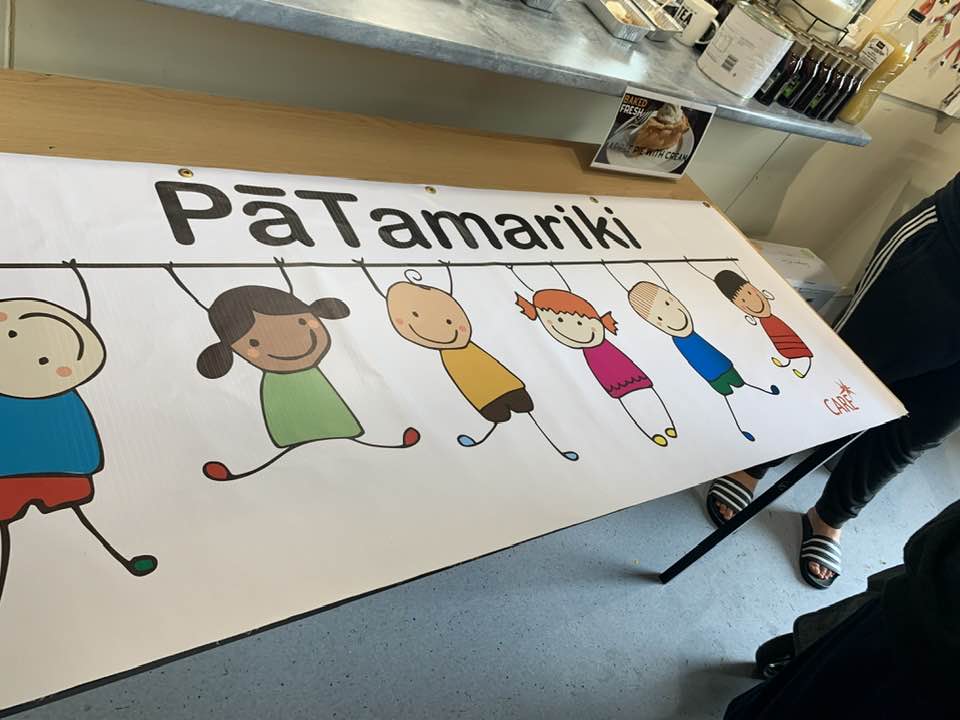

The Highbury Advisory Rōpū, built by tangata whenua community researchers at the Center for Culture-centered Approach to Research and Evaluation (CARE) in partnership with the community in Highbury, has been working hard over the last many months to put together the community-led culture-centered social cohesion intervention called Pā Tamariki. Drawing upon the Māori concept of Pā as a protective space that nurtures the community and supported by funding from the Lotteries Community Grant, the advisory Rōpū envision social cohesion as emergent from the everyday spaces of care, connection, and love in the community.

Pā Tamariki is built with the goal of bringing the whanau and the community together in Highbury to create and sustain a strong community that protects and safeguards the children and the youth.

According to Venessa Pokaia, lead community researcher and community organizer at CARE, “the idea of the Pā as a generative space in the community brings the community together to build positive pathways for the youth. In doing so, the Pā connects the many diverse groups in the community, creating dialogues between the groups and connecting them together in the work of creating a strong community that supports the youth.”

The opening event on Saturday, December 17, witnessed diverse communities in Highbury come together to build this space of dialogue, understanding, care and support, anchored in manaakitanga. Through sharing food, games, and community activities, Pā Tamariki offered a message of hope for Highbury, that positive transformations can come about when community members connect with each other.

The Pā Tamariki campaign builds on the earlier campaign “I Choose Highbury” that was designed by the Highbury Advisory Rōpū to challenge and shift the dominant deficit-based narrative around Highbury. It centered stories of Highbury as a space for positive community interactions, community support, and community mutual aid. The “I Choose Highbury” campaign was launched at a Matariki celebration event in 2020, and was accompanied by community-led community garden initiatives, community cupboards, and community-driven public education programmes on the prevention of violence.

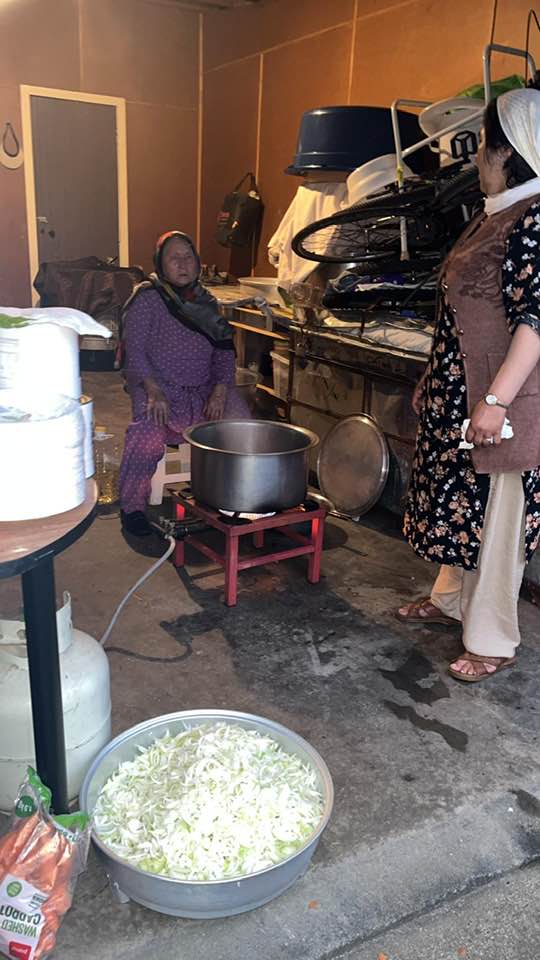

The Pā Tamariki event showcased activities that connected them to culture, offered interactive games, and enabled intercultural interactions among diverse communities residing within Highbury. The hāngī put together by the community after three decades and the food prepared by the Afghan refugee community demonstrate the power of community sovereignty, when communities at diverse intersections come together to create spaces for love, care, and generosity. The organising power of the Highbury Advisory Rōpū demonstrates the effectiveness of culture-centered community-led interventions when power is transferred into the hands of communities as drivers of social change communication. Community sovereignty, the capacity of the community to make decisions and drive change, lies at the heart of positive transformations.

Massey News: Pā Tamariki event brings the communities of Highbury together