Q & A with Prof. Mohan Dutta by Gabriella Davila, Senior Communications Advisor, Massey University

Staff questions and answers

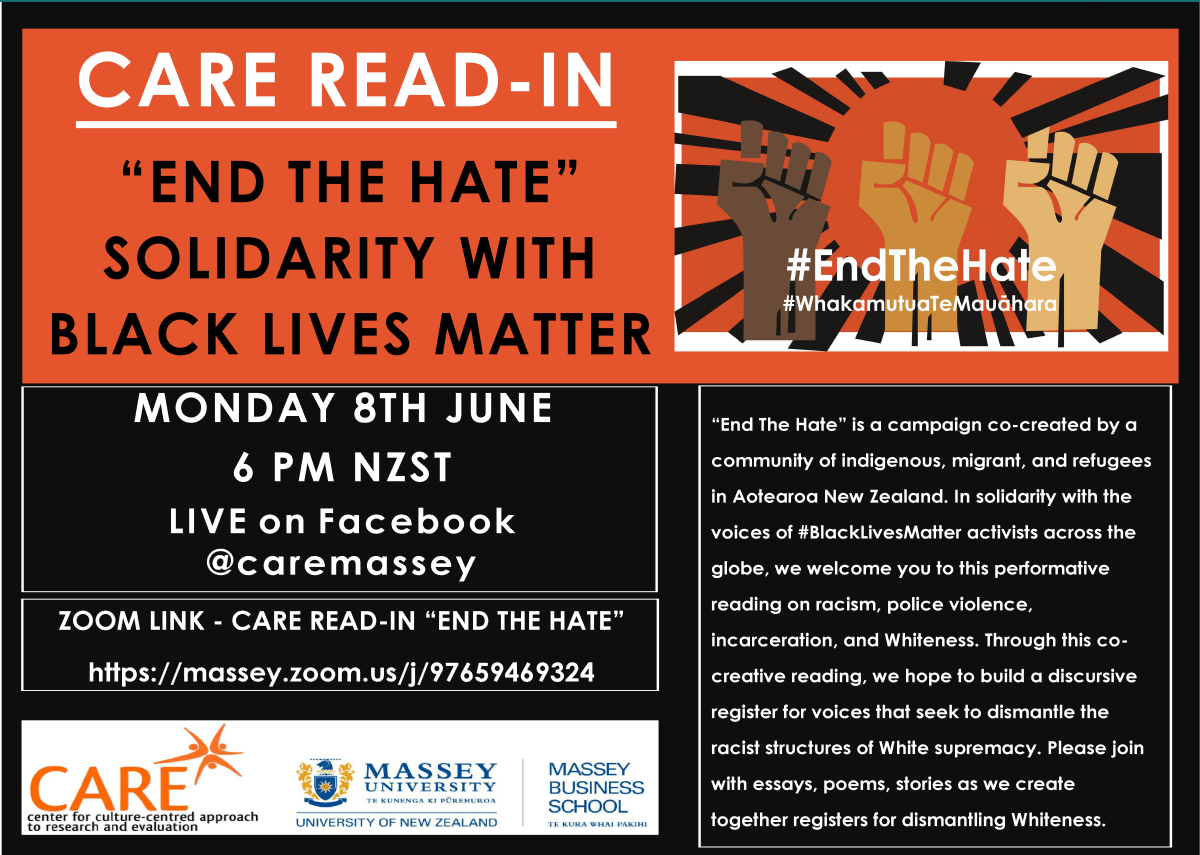

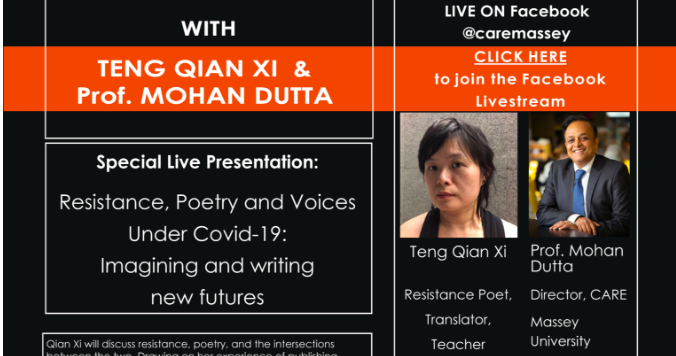

Professor Mohan Dutta is the Director of global research hub, Center for Culture-Centered Approach to Research and Evaluation (CARE) which relocated to Massey in 2018 from Singapore. He is also Dean’s Chair, Professor of Communication at the School of Communication, Journalism, and Marketing.

His research examines marginalisation in contemporary health/healthcare, health care inequalities, the intersections of poverty and health experiences at the margins, and the political economy of global health policies.

Mohan has received more than $6 million in funding to work on culture-centered projects of health communication, social change, and health advocacy. Working broadly on social change interventions designed to achieve the sustainable development goals Mohan has directed seven documentaries, run more than 20 360 degrees advocacy campaigns, and guided the building of various wellbeing infrastructures from irrigation systems and cultural spaces to health care systems and city design. His impact on global policy-making is evident in his advisory roles with the World Health Organization (WHO), United Nations Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF), and The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO).

He has written and edited 10 books and more than 200 articles and book chapters. Earlier this month, he published the book, “Communication, culture and social change: Meaning, co-option, and resistance” with Palgrave MacMillan. He has previously been recognised as an Outstanding Applied/Public Policy Communication Researcher of the ICA and Outstanding Health Communication Researcher of the National Communication Association). Earlier this month he was named a Fellow of the International Communication Association

Can you tell us about your childhood?

I grew up in a middle-class family in a town called Kharagpur in West Bengal, in the eastern part of India in a family of teachers, union organisers, Left party workers, and activists. My childhood in many ways was very simple but also enriching, surrounded by people that were engaged in wanting to make change in the world.

I also grew up in what’s called in India a joint family which is quite similar to the concept of whānau in Aotearoa. We had this one house where two of my dad’s sisters and seven brothers all lived together with my grandmother who was the matriarch and played a key role in holding the family together. I was brought up with 18 cousins and it was quite beautiful in terms of this idea of a collective and a broader whānau caring for each other. This collective played a big role in terms of my own learning and support because when I got a scholarship to go study in the US, for instance, even just arranging the flight ticket didn’t just fall on my dad. My uncles and cousins all chipped in to pay for that money and that is how the broader collective is organised.

What did you like learning when you were a child?

My interests were pretty wide ranging. I loved sciences very much and I did my undergraduate degree in engineering. I really loved maths, physics, biology, and at the same time I also loved English, geography and history.

Learning happened for me inside the classroom but also outside of the classroom and I learned being on picket lines with say an uncle or being a street performer. When I was around 11 or 12, I started performing in many street plays with the Indian People’s Theatre Association (IPTA) and often the plays were held at protest marches. When I was growing up, India had strong spaces of resistance against The General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT). And those were great moments of learning because they taught you in terms of the power of a broader collective and building registers for change against the individualising logics of neoliberalism.

Can you tell us about your most inspiring teacher and why?

My eldest uncle was the headmaster of the local school and I learned a lot witnessing how transformative his impact was, certainly not just in the small little community but in the broader township where we lived and his ability to touch lives.

I had another uncle who was a maths teacher and a union organiser. Early in the mornings on the weekends, children of many different ages would come to our house or sit down with him and learn in an open space. I think that those moments taught me that teaching can be transformative, it can create pathways of mobility for others, and it can make a big difference in society.

How and when did you decide what your career would be?

After I completed my undergraduate engineering degree from the Indian Institute of Technology (IIT), I realised I didn’t want to continue with engineering and instead I wanted to do something that had to do with human beings and connecting with them and interacting with them.

It seemed to me that in very disenfranchised communities, the challenge of wellbeing was not one of developing engineering and more technical solutions, but really a challenge of communication in terms of how to communicate and where communities can have a voice in creating policies and solutions that address their needs.

I think that interest in wanting to develop a pedagogy of voice and how those communities have a say was the turning point. I realised that my training as an agricultural engineer at an elite Indian university that produces technology leaders (many CEOs and technopreneurs across the globe are IIT graduates) was quite limited because it didn’t really teach you how to work with the communities that you wanted to develop solutions for. Communication was and is often the missing link, when you consider the challenges of poverty, health and wellbeing, clean drinking water, decent work, inequality and justice outlined by the Sustainable Development Goals.

In one sentence can you describe the purpose of your present position?

I am the Director of Center for Culture-Centered Approach to Research and Evaluation (CARE) and what we do as a collective of researchers, community organisers, activists and communities, is to develop methods of communication and radical democracy so that communities can have a voice and really, have a say in the policies and solutions that are created, and in defining the futures that they would like to live in.

How did you decide to relocate CARE to New Zealand?

CARE’swork is with very disenfranchised communities and there can sometimes be some significant challenges when working within specific authoritarian contexts such as Singapore, neo-fascist India under the Modi regime, or China. Certainly, the Center was up against some significant state pressures when working with rights of low-wage migrant workers and questions of poverty in Singapore.

After pushing against the system and the structure for six years, I was at that point thinking what could this look like if CARE was in a system that was more aligned with its values and philosophy.

We had a number of choices in terms of whether to move the research centre to the US, and whether to move to some other parts of Asia such as Hong Kong, but New Zealand was really appealing because of the confluence of the politics and the ethics of care in the country.

Do you believe that what you do changes people’s lives?

Absolutely. I want to say this with humility, that as an academic who works on communication for social change, one learns very quickly that change takes a long time. It also takes a lot of commitment, not just in terms of one’s role as an academic but I think the commitment of people and communities and other researchers and activists to make change happen.

Having said that, I think that we have a lot of evidence that what we do actually impacts lives and contributes to better outcomes of health and wellbeing. For instance, when you witness our work in rural India in very disenfranchised indigenous communities living in extreme poverty, CARE’s work has translated into building sources of clean drinking water. These communities would otherwise have to dig deep into the ground and get water through a filtering process. In those contexts, we work on developing community democracy to get access through development structures and institutions to clean drinking water.

We work with people on developing methods of advocacy and activism and this very idea of community democracy succeeds in very tangible ways. From designing development infrastructures rooted in democracy to designing hospitals, cities, and health care systems that are anchored in social justice, CARE makes real impact in people’s lives. Also, our work in communities is not episodic. Instead, these are sustained interventions developed through a commitment of a lifetime.

What do you like doing when you’re not working?

Fatherhood brings much joy and meaning in my life. Debalina [wife] and I have three children and we hang out with them, take them places and play with them. That really takes up the rest of the time outside of work. I am privileged and blessed being a father and really enjoy it.

Source: Gabriella Davila, Senior Communications Advisor, Massey University.