This talk unpacks the form and nature of white supremacist extremism

Hate Effects of Jai Shree Ram: Professor Dutta Explores Ayodhya Temple’s Role in Hindutva Mobilization Across India

In this final video of the series on The Hate Effects of Jai Shree Ram, Professor Mohan Dutta discusses the Ayodhya Temple as the backdrop for the broader mobilisation for Hindutva across India. He argues how Ayodhya serves as an entry point for the ongoing organisation of Hindutva, aimed at attacking Muslim spaces and heritage sites to establish India as a Hindu nation.

You can watch other videos from The Hate Effects of Jai Shree Ram series here:

Video 5

Video 4

Video 3

Video 2

Video 1

Hate Effects of Jai Shree Ram: Professor Dutta Explores How Ayodhya Temple Celebrations Fuel Hindutva’s Narrative of Hindu Pride

Professor Mohan Dutta, Director of CARE, sheds light on how videos circulating on X (Twitter) depicting the celebrations surrounding the inauguration of the Ayodhya Temple become mobilizing anchors for deploying the narrative of Hindu pride. Within this narrative of reclaiming the lost glory of Hinduism, violence is legitimised. Portraying the Hindu majority as victims of Muslim invaders and framing sites of grievance as the politics of grievance, while depicting minorities as perpetrators of crimes, often form the architecture for violence and fascist organising, a key feature of Hindutva.

You can watch other videos from The Hate Effects of Jai Shree Ram series here:

Video 5

Video 4

Video 3

Video 2

Video 1

The Hate Effects of Jai Shree Ram – Video 2

In Video 2 of the series The Hate Effects of Jai Shree Ram, Professor Dutta brings to light videos that surfaced on X (Twitter) where Hindutva mobs are seen attacking Muslim shops and Muslim shop owners, while chanting “Jai Shree Ram.”

You can watch other videos from The Hate Effects of Jai Shree Ram series here:

Video 5

Video 4

Video 3

Video 2

Video 1

Hindutva, Violence and the Ayodhya Temple: Interrogating the Diaspora

In this brief talk, Professor Mohan Dutta will explore the demolition of Babri Masjid that shapes the movement for the Ayodhya Temple, in the form of the Ram Janmabhoomi movement. He will trace the role of the Indian diaspora in the architecture of Hindutva violence and the network of populist politics. Activists from the diaspora and challenging hate will respond to the talk.

Special Presentation: Hate, Hindutva & Ayodhya Temple

In this talk, Professor Mohan Dutta discusses the politics of hate reflected in the celebration of the establishing of the foundation for the Ram Temple in Ayodhya, which sits on the demolition of the Babri masjid.

Join us at 8pm (NZT) by following our link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=amPu_QHJOcU.

The talk was recorded on 4 August 2020 @ 1 pm NZST.

And while you’re watching, join our YouTube Channel with a Like & Subscibe!

Cultural essence, cultural nationalism and the figure of the “Miya:” The frontiers of anti-Muslim hate in India

on April 11, 2023 by Prof. Mohan Dutta

The figure of the “Miya” forms the infrastructure of the anti-Muslim hate in Assam, the Northeast frontier of India.

In this essay, I will argue that the genocidal hate reflected in anti-Muslim violence and anti-Muslim public policies in Assam is mirrored in the ongoing production of the “Muslim other” in the infrastructure of the fascist National Register for Citizens (NRC) carried out by the Hindutva regime.

The rhetorical trope of the “Miya” depicts the power of cultural discourse in organizing violence through the turn to a monolithic cultural essence based on exclusion.

The construction of the “Miya” as the Muslim other lies at the core of the cultural chauvinism that has historically mobilized the middle-class, upper-caste cultural nationalist movement in Assam. Elsewhere, I have described the communicative tools that actively produce “the other” to organize cultural nationalism, constructing the nation on the basis of a monolithic cultural essence.

The term “Miya” is rife with the racist fear of the Muslim illegal immigrant taking over Assamese land and culture, mobilized to build a movement of cultural nationalism. It is often used to describe Muslim migrants from the Myemensingh region of neighboring Bangladesh (which was part of undivided Bengal) who migrated in the early twentieth century, encouraged and in many instances forcibly moved by the British imperialists, settling in the riverine islands of the Brahmaputra river.

The activist-scholar Sooraj Gogoi powerfully describes the ways in which the cultural revivalism that shaped the Assamese nationalism underlying the Assam movement in the 1980s created the discursive climate of fear and hate around the illegal Muslim immigrant, classified as the foreigner. He further describes the role of middle-class caste Assamese cultural workers, intellectuals including academics, poets, lyricists, performers etc. in constructing the discursive ecosystem of cultural nationalism.

The basis of the cultural turn underlying the Assam movement draws on an Assamese essence depicted in linguistic and cultural artifacts. Simultaneously, this cultural turn as cultural nationalism is deployed toward the production of hate through the circulation of the image of the foreigner. Through songs, poems, and graffiti, the foreigner is crafted as a perpetual threat to the cultural essence, as a danger to a monolithic Assamese cultural identity.

This discursive climate of hate is financialized by the political class, turning hate into the basis for mobilizing the movement and political participation. It is this ecosystem of hate seeded by caste Assamese political-cultural society that mobilized largely tribal and oppressed caste communities in participating in the violence at Nellie that resulted in the death of 3,300 Muslims. The Nellie massacre remains one of the most violent pogroms since World War 2.

The xenophobic anti-Muslim violence scripted into mainstream caste Assamese society as cultural nationalism flows seamlessly into the Islamophobic fascist laboratory of Hindutva.

The chauvinism of Assamese cultural nationalism feeds directly into the cultural nationalism of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). The threat of the illegal foreigner in Assam is mobilized into the concept of the registry, crystallized in the National Register for Citizens (NRC), sending Muslims into detention centers, stripped of the “right to have rights.” The violence of the NRC process, marked by the haphazard implementation of documentation, the arbitrariness of the Assam foreigners tribunal, the disenfranchisement of Muslims who have lived in India across generations through incarceration in detention centers (locally referred to as concentration camps), and the absence of access to juridical processes, have resulted in plethora of health challenges, including challenges to mental health and suicides. In a period of five years between 2015 and 2020, between 38 and 42 individuals committed suicide in Assam in the context of the revocation of their own or a relative’s citizenship status.

The discursive construction of Muslims as foreign nationals is built on the ideology of border-making that catalyzes the material construction of the border as the basis for othering. This process of othering Muslims as the basis of cultural nationalism in Assam reflects the organizing role of cultural essence as the organizing ideology that drives hate, violence, and fascist politics.

Link to the blogpost on: https://culture-centered.blogspot.com/2023/04/cultural-essence-cultural-nationalism.html

Image source via google search: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-india-violence-idUSBRE86N1CE20120724

#CAREMasseyNZ #CAREDirectorsBlog #CulturalEssence #CulturalNationalism #Miya #AntiMuslim #Hate #India #NationalRegisterForCitizens #NRC #SoorajGogoi #MasseyUni #Aotearoa #NewZealand

CARE Op-Ed: A RESPONSE TO CHRIS WILSON’S REVIEW OF BYRON CLARK’S “FEAR:” THE LIMITS OF ACADEMIC EXPERTISE

by Prof. Mohan Dutta, | February 16, 2023

I have been so looking forward to reading Byron Clark’s “Fear.”

Over the past three years, as I have read and watched Clark’s analyses of the far-right ecosystem in Aotearoa New Zealand, I have come to respect his evidence-based analytic work that is at the same time activist, directly responding to the threats to marginalized communities posed by far-right extremism.

His analytic work has been critical to the ongoing challenges to far-right extremism led by activists.

Byron’s knowledge of the hate ecosystem emerges directly from the empirically grounded challenge he has posed to this ecosystem by placing his body on the line. It is worth pointing out here, that like many other activists in this space, Byron mostly does this work as unpaid labor, and he sustains himself through his day job (I will return to this point toward the end of the article).

So, when some of my activist interlocutors whose work challenges Islamophobic hate in Aotearoa sent me a review of Byron’s book by Chris Wilson, I was disappointed to read it.

Let me note at the beginning that Wilson begins his review by praising Byron for his work exposing a range of what Wilson terms fringe political ideologies. He then goes on to point out places where the book could have been improved, specifically in its definition of terms and presentation of evidence.

I will focus here on a particular part of Wilson’s review, his suggestion that Clark presents no evidence of a Hindutva threat in Aotearoa.

What counts as evidence

In his review, writing about Hindutva, Wilson writes:

“For example, Hindutva is presented as present and threatening in New Zealand, but with little to no evidence. Because of a lack of demonstrable activity or presence here, the author uses the fact that the New Zealand Hindu Council is affiliated to the India-based nationalist organisation VHP, to discuss in much greater length the VHP’s extremist activity in India, even including a discussion of the riots in Gujarat in 2002.”

This paragraph is flawed in its argumentation.

It begins with the claim that Clark presents Hindutva as threatening in Aotearoa, “with little to no evidence.”

Note then the following sentence that points to Byron’s observation that the New Zealand Hindu Council is affiliated to the India-based nationalist organisation Vishwa Hindu Parishad (VHP).

That Clark has established the link between the New Zealand Hindu Council and VHP is itself evidence of the threat to social cohesion in Aotearoa posed by Hindutva.

Also consider here that Wilson doesn’t operationalize the concept of threat; so what is he assessing Clark’s evidence on the basis of is largely unclear.

If we take social cohesion as the value to uphold (my insertion of a value), that the New Zealand Hindu Council is affiliated to the India-based nationalist organization VHP is of great concern here in Aotearoa. I have personally learned about the threat posed by Hindutva-aligned organizations such as the VHP to New Zealand democracy (including academic freedom) the hard way.

A number of Indian-origin community members, including Indian minorities and Indian activists in Aotearoa have documented the threat posed by Hindutva to democracy and social cohesion in Aotearoa. In March 2021, a Sikh youth had been attacked online in New Zealand.

Wilson then goes on to write:

“This history of violence and extremism in India will give many readers the impression that something similar is present in New Zealand, when no evidence has been provided for this inference.”

The sentence above is ambiguous and lacks clarity. The ambiguity itself is strategic, not naming Hindutva as the driver of the violence and omitting the robust body of evidence on the nature of the VHP and other affiliated Hindutva organizations as right-wing extremist groups and their roles in violence.

Wilson’s account bypasses this history of violence and extremism in India directly connected to the VHP, instead making a generic statement about the history of violence and extremism in India.

Consider here that the VHP has been linked with attacks on Muslims and Christians, organized attacks on mosques and churches, destruction of the Babri masjid, and various incidences of violence across regions.

Hindutva is a radicalizing force globally, leading to violence in the Indian diaspora across Western democracies. It has been linked with violence in United Kingdom, Canada, and Australia.

Much like the Hindutva attacks that targeted me and other academic researchers at the Center for Culture-centered Approach to Research and Evaluation (CARE) at Massey University (note here that New Zealand Hindu Council and Hindu Youth were key organizers of these attacks), Hindutva-related trolls and organizations have attacked academics globally, posing direct threats to academic freedom and democracy.

CARE’s research has documented the online infrastructure of Hindutva in Aotearoa New Zealand. The activist group Aotearoa Alliance of Progressive Indians (AAPI) has consistently and systematically highlighted the presence of Hindutva in Aotearoa New Zealand including the role of the New Zealand Hindu Council in spreading disinformation as an organization affiliated with Hindutva. AAPI has raised critical concerns of relationships between community leaders in Aotearoa New Zealand and Hindutva.

That the association of New Zealand Hindu Council with VHP doesn’t count as evidence of threats posed by Hindutva to Wilson is of concern, particularly given his expert role on countering violent extremism. Although Wilson is not discounting the presence of Hindutva in Aotearoa New Zealand, his argument about what counts as evidence for an organization to be counted as threat raises the question whether the incidences outlined above meet Wilson’s threshold of a threat. Alas, we wouldn’t know because Wilson doesn’t define the term threat within this context, something he accuses Clark of not doing adequately in his book.

By this logic, affiliation or association doesn’t count as evidence of the presence of a threat. Is the same definitional parameter used by the New Zealand security community when conceptualizing affiliations with organizations such as ISIS (Note here the similarities with ISIS shared by Hindutva).

Moreover, Wilson complains that Clark does not explain why Hindutva should be understood as “far right,” ignoring the evidence that Byron does present of Hindutva’s underlying fascist far-right ideology.

In fact, Byron is one of the few New Zealand-based activists that has engaged activists in the Indian diaspora in dialogue about the threats of Hindutva. One of his earliest analyses of the relationship between the Hindutva proponent Roy Kaunds, Kelvyn Alp and Counterspin media (Wilson does accept Alp and Counterspin as examples of the far-right) offered a conceptual framework for examining the discursive flows between the Islamophobia of Hindutva and the Islamophobia of white supremacy that I have discussed in my public writing.

Performative references to Christchurch

It is ironic that Wilson begins his opinion piece in Newsroom by referring to the Christchurch terrorist attack (that directly targets Muslims, with its attack on mosques).

Yet there is not a single reference to Islamophobia (the driving force behind the Chrictcurch attack and the underlying ideology that connects white supremacists with Hindutva) in Wilson’s essay.

The whiteness (referring to the hegemonic values of white culture, held up as universal) of the extremism industry that has flourished post-Christchurch is marked by similar ongoing gaslighting of the actually existing Islamophobia in Aotearoa New Zealand (including its casual omission).

There is no reference in Wilson’s review of the concerns regarding Hindutva extremism and Islamophobia in Aotearoa expressed by Muslim women activists.

These same activists had earlier raised multiple alarm bells about a potential extremist attack targeting Muslims and driven by Islamophobia. Here’s the noted activist Anjum Rahman speaking about Hindutva:

“It’s extreme hate…It’s dehumanising material, trying to dehumanise our community.”

The Stuff article citing Rahman goes on to note:

“Later, Rahman shares with Stuff social media posts containing abuse directed at Muslims. She’s right – it’s dehumanising and awful. Similar material has been cited in a report from Massey University researcher Mohan Dutta who has studied discrimination against minority groups in India and in the Indian diaspora.”

Context and structures matter

The systemic erasure of the voices of Muslim communities and activists post the Christchurch terrorist attack has been accompanied by the ongoing erasure of the evidence of Islamophobia presented by Muslims.

In our research carried out at CARE with Muslim communities experiencing hate, the ongoing erasure of accounts of evidence is part of the racist structure that upholds and perpetuates Islamophobia. Muslim communities and activists often ask, How much evidence on the drivers of violence is actually evidence that will count for security experts?

And more vitally, when will the accounting of this evidence actually lead to positive policy responses that do something about the drivers of hate.

This ongoing discounting of evidence is accompanied by the systemic individualization of the analytic framework imposed by the expert security community, shaped by the hegemonic values of whiteness.

As focus is turned on identifying, categorizing and surveilling violent individuals, the structural contexts and drivers of violence remain erased from mainstream analytic frameworks. It is this individualization within the security apparatus that fails to see Hindutva’s links to violence (after all, Hindutva supporters in the Indian diaspora are often professionals and members of the successful model minority business community).

Moreover, the absence of structural analysis means that security experts and bureaucrats conveniently turn a blind eye to the actually existing Islamophobia within the security community itself, which fundamentally underlies the perpetuation of Islamophobia.

Silence doesn’t make the problem go away

Toward the end of his review, Wilson suggests that we need to take care about how we describe the various groups under the umbrella of the far-right, conspiracy theorists, and anti-government movements. He suggests that not taking adequate care in defining these groups would likely push them together, generate misplaced fear, and contribute to rising polarization.

I agree with Wilson. We need to take great care in defining the various groups that threaten democracy and social cohesion and develop appropriate response strategies that are nuanced.

At the same time, digging our head in the sand and pretending these groups don’t exist or they don’t pose a threat to our social cohesion is not going to curb the rising polarization. In fact, doing so might fuel further polarization.

Not counting, categorizing and adequately responding to the threat posed by Hindutva in Aotearoa New Zealand is likely to further heighten the sense of marginalization felt by Indian minorities here. Moreover, such discounting of evidence is likely to empower Hindutva ideologues here in Aotearoa New Zealand to continue to target social cohesion and democracy.

Without adequate structural responses and frameworks for empowering communities at the margins in the Indian diaspora, the inter-communal threat posed by Hindutva is likely to go unchecked. We can’t wait for Hindutva violence to show itself for us to then respond to it post-hoc. Lessons learned from Christchurch, Australia, Leicester ought to offer us insights into strategies for countering Hindutva.

What qualifies you as an expert

Talking about credentials, historically, we have turned to academic expertise as the basis for generating knowledge. This knowledge then has shaped how we have historically crafted policies, developed interventions, and responded to these interventions.

Knowledge, therefore, is directly tied to policies.

Given the severe lack of diversity in academic disciplines, this has meant that academic knowledge informing policy formations is also severely limited. The absence of minority communities who are the targets of majoritarian hate and violence from decision-making spaces has meant that conceptual frameworks are largely absent in addressing the hate and violence.

Consider the area of terrorism and conflict studies and the ways in which this area has been shaped by academic expertise. That the area has been largely dominated by whiteness and imperial agenda has meant that what is operationalized as terror and therefore placed under surveillance has been grossly shaped by Islamophobia post-9/11. The prevailing ideology of the “War on Terror” has over-surveilled Muslims, mainstreamed the racist targeting of Muslims, and legitimized the terror narrative that drives Islamophobia. Ultimately, the mainstreaming of the Muslim terror narrative is directly tied to the accelerated growth of Islamophobic white supremacist and Hindutva hate post 9/11.

In this backdrop, the work of activists such as Byron Clark is vital to generating knowledge and to countering the myopic frameworks of analysis imposed by academic experts.

I have found my own knowledge of studying social change as constrained within the rules and norms of academia. These rules and norms themselves are often established within the structures of whiteness, the hegemonic values of white mainstream academic culture.

Working with activists in CARE’s activist-in-residence programming and learning from their knowledge I have found brings critical insights that shape the mobilization toward structural transformation.

The ability to see broad linkages and to explore these linkages is vital to mapping the far-right threat to social cohesion and democracies globally. I am so glad that Byron has dedicated a Chapter on Hindutva in his book. For the Indian diaspora minority communities and activists who have witnessed the accelerated growth of Hindutva in Aotearoa over the past decade, Byron’s intervention is vital to placing in the mainstream their concerns about hate.

#CAREOpEd #Fear #Hate #Hindutva #RightWing #Activist #ByronClark #Aotearoa #NewZealand #CARECCA #CAREMassey #MasseyUni

Article Source: https://culture-centered.blogspot.com/2023/02/a-response-to-chris-wilsons-review-of.html

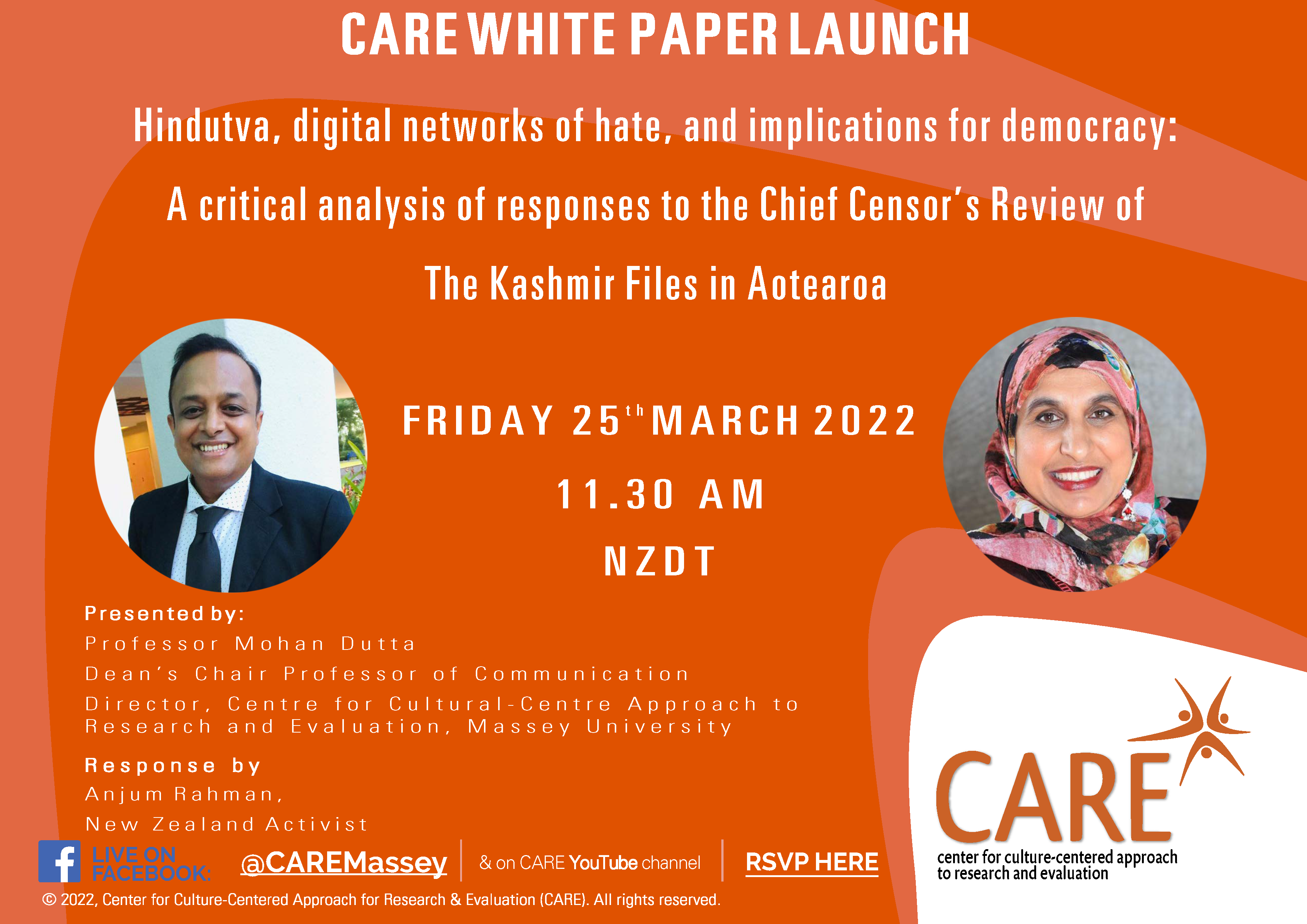

CARE White Paper Launch – Hindutva, digital networks of hate, and implications for democracy: A critical analysis of responses to the Chief Censor’s Review of The Kashmir Files in Aotearoa

with Prof. Mohan Dutta and New Zzealand activist Anjum Rahman

Join us LIVE for the White Paper Launch with Prof. Mohan Dutta and NZ activist Anjum Rahman on Hindutva, digital networks of hate, and implications for democracy: A critical analysis of responses to the Chief Censor’s Review of The Kashmir Files in Aotearoa

Friday 25th March 2022 @ 11.30 am NZDT

Livestream link: https://www.facebook.com/CAREMassey/videos/368615111797393

CARE Facebook Event: https://www.facebook.com/events/1583656381990700/

#Hindutva #DigitalNetworks #hate #democracy #KashmirFiles #Aotearoa #NewZealand