Check out our latest research article published in Frontiers journal.

Title: Culture-Centered Processes of Community Organizing in COVID-19 Response: Notes From Kerala and Aotearoa New Zealand by Prof. Mohan Dutta, Christine Elers and Pooja Jayan, CARE: Center for Culture-Centered Approach to Research and Evaluation, Massey University

Overview: The culture-centered processes of community organizing drawn on the case studies of community organizing in Communist Kerala and in Iwi-led Māori checkpoints in settler colonial Aotearoa New Zealand foreground the vital work of alternative practices of health response, serving as the basis for robust alternative imaginations amid the pandemic.

Here is the link to the full article –

https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcomm.2020.00062/full#h9

#CultureCenteredProcesses #CommunityOrganizing #COVID19Response #Kerala #Aotearoa #NewZealand #CCA #CAREMassey #CARECCA #MasseyCJM #MasseyUni

The culture-centered approach (CCA) foregrounds the organizing role of communities at the “margins of the margins” of the globe as the spaces for identifying the structural challenges to health and well-being and for co-creating community-anchored solutions to these challenges. Pandemics such as COVID-19 render visible the deep-rooted inequalities across and within societies, seeded and catalyzed by over three decades of variegated neoliberal reforms. The trajectories of COVID-19 outbreaks as well as the effects of COVID-19-related policies render visible the inequalities that are written into the neoliberal organizing of political economy. Community participation is scripted into the neoliberal framework as an instrument for depoliticizing community and utilizing it as a channel for disseminating top-down individual behavior change messages. Drawing on the examples of community organizing in Kerala where the Communist Party of India (Marxist) has actively co-created an infrastructure for socialist organizing, and Iwi-led Maori checkpoints in Aotearoa New Zealand, we delineate the features of transformative community organizing. Community organizing in the CCA is political, foregrounding community sovereignty as the basis for resisting neoliberal health structures. Community struggles for communication equality thus point to alternative forms of organizing health and well-being that challenge and seek to dismantle neoliberal governmentality.

The culture-centered approach (CCA) foregrounds the organizing role of communities1 at the “margins of the margins”2 (Dutta, 2020a) of the globe as the spaces for identifying the structural challenges to health and well-being and for co-creating community-anchored solutions to these challenges. Pandemics such as COVID-19 render visible the deep-rooted inequalities across and within societies (Dutta, 2016, 2020b, 2020e; Ahmed et al., 2020; Van Lancker and Parolin, 2020), seeded and catalyzed by over three decades of variegated neoliberal reforms (Brenner et al., 2010). The trajectories of COVID-19 outbreaks as well as the expulsions and displacements produced by COVID-19 policy responses across states foreground the urgent necessity of structurally directed social change communication amid the pandemic. As witnessed across the globe, COVID-19 is reproducing, catalyzing, and circulating existing inequalities that have been produced by increasingly extreme neoliberal reforms, further exacerbating the already disenfranchising conditions experienced by large proportions of those at the “margins of the margins” (Dutta, 2020a). The process of cultural centering anchors communicative responses to pandemics in community voices, constituted in the work of everyday organizing for radical democracy in communities at the margins to transform the unhealthy structures and generate socialist state responses owned by and accountable to communities. The spaces for community voices at the margins make visible the violence entrenched into market-promoting neoliberal reforms, and the powerful effects of these reforms on human health and well-being; simultaneously, these community spaces re-organize local-regional-national-global linkages in the rationality of communicative, political, and economic equality (Dutta, 2016).

Meaningful responses to pandemics are constituted in communities, situated amidst grassroots democratic decision-making and community negotiations of the structural contexts of the pandemic. The organizing role of communication draws on the agentic capacities of communities in identifying and responding to challenges through the ongoing work of building dialogic infrastructures for community voices. Communication is constitutive of community, and mediates community action through an iteratively reflexive process of interrogating power (Dutta and de Souza, 2008). It forms the infrastructure, fabric, and texture of community life and is in turn, constituted by community. Drawing on the extant scholarship on the linkages between communication and community in the CCA, we theorize communication as the organizing space for co-creating responses to the pandemic. As a resource embedded in everyday community life, communication brings together people in spaces, creating the basis of shared values, shared meanings, and shared actions. These shared values, meanings, and actions form the basis of local, national, and global responses to pandemics. We argue that democratic community action in pandemic/crisis response is strengthened when state structure support socialist economic organizing, guaranteeing the fundamental resources of health as a human right.

In its role as a dialogic anchor for creating connections, communication brings the “margins of the margins” in collectives, and organizes and sustains relationships that form communities. The manuscript draws on two case studies of emergent success in responding to COVID-19, one from the Indian state of Kerala and the other from the context of Maori organizing in Aotearoa to depict the organizing roles of communities in interplay with the organizing structure of the state in responding to COVID-19. Both the state of Kerala under the Communist Party of Indian (Marxist) and Aotearoa New Zealand under Labor reflect a certain level of commitment to socialist political-economic organizing, although this is negotiated amidst turns toward neoliberal policies internally as well as within a broader global climate of pressures exerted by the transnational capitalist class and international financial institutions (IFIs) for further neoliberal reforms. In the case of Kerala, the response of the democratically elected Communist state is situated within a broader anti-science neo-fascist right-wing federal government further pushing extreme neoliberalism within an already neoliberal structure (Cammaerts, 2020). Through this comparative work that delves into local, national, regional, and global responses, we examine closely the role of community organizing rooted in radical democracy in relationship with processes of socialist state organizing in constituting effective pandemic response. Our analysis of responses and comparison of community responses foregrounds the following key threads in community organizing in response to COVID-19: (a) addressing structures, (b) mobilizing resources, (c) drawing on cultural values, (d) anchoring in social justice, and (e) fostering spaces for democratic ownership.

Drawing on the key tenets of the CCA, we explore community organizing that co-creates communication infrastructures for imagining, creating, and sustaining socially just responses to the pandemic at the global margins. The communication infrastructures work toward fostering communicative equality through the democratization of spaces of decision-making, while simultaneously negotiating continually a politics of structural transformation based on an ongoing commitment to socialist principles for organizing health, education, housing, food, and work (Dutta, 2008, 2011, 2016; Dutta and de Souza, 2008). Organizing processes that foster socialist radical democracies at the global margins address both the trajectories of spread of the virus as well as the overarching structural inequalities that constitute deep unequal effects of pandemic response policies. Culture-centered health communication interventions recognize the material inequalities that constitute health and well-being, thus imagining broader transformations in economic structures, with fundamental provisions of universal basic income, universal housing, universal food, and universal health. The two cases offered for comparison in this manuscript will empirically examine the forms of communicative response anchored in culture-centered processes that seek transformations in political, social, and economic organizing3. In resistance to the hegemonic framework of health communication that keeps neoliberal structures intact through individualizing responses, communities at the margins as spaces of democratic response offer imaginaries for organizing health and well-being that are not only responsive to COVID-19 in the short term, but also potent in their transformative capacities for re-organizing political economies (Habersaat et al., 2020).

Culture-Centered Approach and Pandemic Communication

Working with the question of voice, the CCA examines the sites of erasure in hegemonic formations, the various layers at which erasures are codified into these structures, and the ways in which voices are erased from spaces of decision-making (Dutta, 2005, 2007, 2018, 2019). These erasures of voices, especially voices from communities at the margins, are situated amidst an overarching ideology of neoliberalism that positions health problems as problems of individual behavior, to be targeted through expertise-driven top-down models of health communication. The locus of decision-making is driven by experts, with elite technocratic managerialism driving health communication. The behaviors recommended as well as the communication surrounding the recommended behaviors are located in the ambits of expertise. Very much embedded within the logics of the neoliberal status quo, models of pandemic communication problematize the pandemic as resulting from the behaviors of individuals. Pandemic communication in the hegemonic framework targets individual attitudes, knowledge, and behavior, then proposing messaging strategies directed at changing these individual behaviors in order to stop the spread of the pandemic.

Entire industries of behavior change communication have been put forth within the hegemonic logic of individualized health communication, while simultaneously backgrounding the structural inequalities that form the fabrics of health problems. In the context of pandemics, the structural violence that constitutes the trajectories of spread of the pandemic as well as the precarities that are reproduced by the pandemic are rendered invisible while communities at the margins are turned into targets of top-down expert-led interventions. The problematization of health in the realm of individual behavior thus keeps the neoliberal structures intact, circulating erasures of the margins (Dutta, 2018, 2019). Resisting this neoliberal model of privatized individualism, the CCA centers the interplays of culture and community in health communication (Dutta, 2007, 2008; Dutta and Basu, 2008). In the context of pandemic communication, the foregrounding of community voices at the margins interrogates the hegemonic narratives of pandemic response, building structurally directed advocacy and activist interventions. The behavior change framework constituting the ideology of pandemic response globally is interrogated through the presence of subaltern voices that have hitherto been erased (Dutta, 2004).

Community Participation

Community participation serves as a register for bringing about change that is meaningful to the community (Dutta, 2018). The participation of the community is essential for comprehending the problems as experienced by community members, and creating solutions that are meaningful to their lived experiences (Dutta, 2004). Through evidence-based knowledge grounded in cultural meanings and everyday understandings embedded in community life, communities emerge as anchors to developing health communication solutions. In contrast to the concept of community participation serving as a conduit for diffusing the neoliberal agendas of hegemonic health communication solutions, community participation in the CCA is re-organized in the logics of organizing at the margins anchored in an active politics of resistance. The impetus of community participatory processes in the CCA emerges from within the margins as the basis of expressing individual, familial, and collective agency. The process of cultural centering re-works culture as an infrastructure of drawing on community values, community norms and community narratives to put forth health solutions that challenge the hegemonic structures and the capitalist/racist logics that constitute these structures.

Community Participation, Co-optation, and Neoliberalism

Community participation in the neoliberal ideology constitutes community as a depoliticized space for disseminating the top-down interventions designed by technocratic elites. Community-based participatory interventions, funded by neoliberal organizations such as the World Bank, International Monetary Fund, development agencies (USAID) and global foundations (Gates, Ford) organize communities as spaces for self-help, while simultaneously catalyzing the depletion of public resources and infrastructures (Dutta, 2013). Community voice, incorporated as community participation in hegemonic health interventions, serves the agendas of neoliberal expansion, incorporated into the ideology of growth as development. Participatory agency of communities at the margins is coded into self-help programs of community engagement that reproduce the ideology of the global free market, with individualized health solutions disseminated through community participatory infrastructures (Dutta, 2017). Participation serves to perpetuate the neoliberal ideology, constructing it in culturalist language, and developing culturally sensitive health communication solutions that perpetuate the neoliberal status quo. Participation maps and domesticates dissent, depoliticizing communities and incorporating subjects as engaged stakeholders to consolidate state-capitalist power configured in technocratic logics. Participation is an instrument for control and disciplined management built on the idea that voters are irrational, ignorant, and incapable of making informed decisions.

Community Participation and Resistance

The CCA positions community participation in resistance to this co-optive nature of participation in the service of global capital. Noting that the hegemonic forms of participation established within the ambits of the WB or global Foundations serve the expansionary logics of global capital, culture-centered interventions root themselves in the actual lived politics of co-creating communicative infrastructures for democracy at the global margins. Health is theorized amidst the participation of those at the global margins in processes of resisting hegemonic structures, foregrounding local meanings, and working with these meanings to mobilize for change. The work of community participation in the CCA is centered on building spaces community democracy, centering community voice infrastructures in the participation of the “margins of the margins.” The recognition that communities are not homogenous guides the co-creation of community infrastructures for the voices of the “margins of the margins.” The framework for who participates and what the rules of participation are therefore emerges from within community spaces, guided by the conceptual anchors, “whose voices are missing from this discursive space,” and “how can we co-create communicative spaces that seek out those at the margins.”

Noting that voices from the margins reflect local agency, culture-centered processes attend to the agentic community ownership of the local organizing frameworks, which serve as the basis of securing health and well-being (Dutta, 2007, 2011, 2015, 2018; Basu and Dutta, 2009). Entrenched communicative inequalities are addressed through the co-creation of communicative processes of building spaces of local participation, embedded in local ownership over democratic processes of decision-making (Dutta et al., 2019), social change emerges from the imaginations of subaltern communities in the Global South. The CCA centers meanings as the basis of knowledge production, working with meanings to build infrastructures for securing resources, transforming politics, and co-creating infrastructures at the margins. These locally situated meanings therefore serve as the basis of theorizing communication for health and well-being. In the context of COVID-19, meanings of everyday health and wellbeing guide the organizing of communities, movements, and political parties.

The CCA suggests that de-centering the top-down framework of COVID-19 response calls for exploring expressions of collective agency at various levels and in various forms, including in communities, in workplaces, in worker unions, in civil societies, and in policy infrastructures that are critical to creating and sustaining responses anchored in care and justice. The pandemic constitutes the backdrop for the emergence of communicative leadership across spaces from communities to nation states to global organizations. In contrast, the absence of communicative leadership strains existing resources, seeds divisiveness, further fosters disinformation, and exacerbates the struggles experienced by the margins of highly unequal societies. COVID-19 makes visible the deep inequalities in contemporary political and economic organizing; it is in this backdrop that communities emerge as spaces for re-organizing meanings, conceptual anchors, and political economic systems.

Hegemonic COVID-19 Responses

Hegemonic COVID-19 responses, situated within the framework of top-down, expertise-driven behavior change interventions constructs the spread of COVID-19 amidst individual-level behavior. The behavior change strategies and recommendations, formulated by dominant state actors, are framed as individual behaviors. The framing of behaviors in the realm of the individual perpetuates the neoliberal status quo, leaving intact the logics of “flow,” “free market,” “global movements,” and “privatization of resources” that have led to the deep inequalities evident amidst COVID-19.

COVID-19 and the New Zealand Government’s Response

As the global COVID-19 pandemic surfaced in Aotearoa, New Zealand, Prime Minister, Jacinda Ardern, announced on 23 March 2020 that New Zealand would move into lockdown level four at 11:59 p.m. on Wednesday 25 March 2020. On the announcement date, there were 102 positive cases of COVID-19 in New Zealand. The majority of cases were linked to overseas travel and two cases were treated as community transmission (Ministry of Health, 2020, Strongman, 2020). Sobering images of strained public healthcare systems and the rapid escalation of COVID-19 cases causing death from Italy and other infected areas of the world circulated social and national media prompting New Zealand’s decisive elimination strategy to “go hard and go early” (Ardern, 2020 as cited in Hickey, 2020). It could be argued that global shortages of valuable ventilators to treat severely ill patients also influenced the government’s strategy that closed all borders and locked down the country. A public health stock audit revealed that there were 520 ventilators in the public healthcare system (Checkpoint, 2020) with possible access to another 250 ventilators used by private hospitals and other organizations (Pennington, 2020). Should the hospitals become inundated with COVID-19 patients, the current stock would not be sufficient to artificially ventilate critical patients. Drawn from Bentham’s version of utilitarianism (Gustafsson, 2018) where simply put, acts are justified and should be pursued if they produce the most good for the most people in society, the Italian College of Anesthesia, Analgesia, Resuscitation and Intensive Care published guidelines for doctors working in the intensive care units. These guidelines advised that age and comorbidity rates of infected patients should be considered during the triaging process to maximize the best use of healthcare facilities and equipment (Mounk, 2020; Ovadia, 2020). This reasoning means that the provision of healthcare, a basic humanitarian service, should be deployed for people who present with a greater success of recovery. Should positive COVID-19 cases exponentially rise in New Zealand and the public healthcare system becomes overwhelmed to the point where there are not enough healthcare facilities and equipment for everyone in need, then who decides who will be connected to a potentially life-saving ventilator and who will miss out? In other words, who decides who will live and who will die?

Historical Precedents

Against the backdrop of New Zealand’s colonial settler state, the public healthcare system has failed Māori resulting in over-representation in many debilitating health statistics (Reid et al., 2019; Waitangi, 2019). These health outcome inequalities existed pre-COVID-19. Ngata (2020) highlights that the COVID-19 pandemic has not plunged the country into unprecedented times because like other nations, New Zealand has a historical litany of deadly pandemics that has plagued these shores (Day, 1999; Chapple, 2016, 2018). The Spanish flu’ 1918 pandemic struck deadly rates at 48.9 per 1,000 for Māori, massively higher than the Pākehā (European New Zealanders) morbidity rate of 6 per 1,000 (Rice, 2018).

Day (1999) provides a historical account of the 1913 smallpox epidemic and its prevalence amongst Māori communities. Furthermore, Day explains that the vaccine lymph thought to provide immunization against smallpox was produced for distribution to Māori, not out of kind benevolence but an attempt to curb further infection of Pākehā. Despite the Health department’s publicized intent to distribute smallpox vaccines to Māori communities, Day added that most of the doses were swallowed up in urban areas by Pākehā, resulting in a shortfall with some rural northern Māori communities entirely missing out. Māori were prevented from traveling unless they carried a successful immunization certificate and even then, many were turned back on their journey and barred from entering towns and shops. Although Day notes the discriminating attitudes of Pākehā, her analysis falls short of naming the deep-seated racism that often accompanies pandemics, underpinned by the colonial servitude to Whiteness.

Hegemonic Response in India

It takes a pandemic to render visible the deep inequalities that make up the highly unequal societies we inhabit. As pandemics go, the power of COVID-19 lies in its mobility, along the circuits of global capital, picked up and carried by the upwardly mobile classes feeding the financial and technology hubs of capital. The irony of neoliberal globalization lies in the disproportionate burden of accelerated mobilities borne by the bodies of the poor at the global margins. The poor, whose bodies are the sites of neoliberal extraction, are also the bodies to be easily discarded when crises hit. The images of throngs of people, the poor, now expelled from their spaces of precarious work at the metropolitan centers of financial and technology capital in India, spaces that are projected as the poster-models of mobility in development propaganda, walking on the long walk home, are circulating across our mobile screens (Dutta, 2020c,d). Images of a migrant worker dead after the grueling walk home, a mother pulling her daughter as they try to make their way home, a young man bursting into tears at the sight of food, a father walking as he carries his sleeping daughter on his shoulders, crowds of workers waiting in long lines to board buses, these are the faces of the unequal India made visible by COVID-19. These images of emaciated men and women, with little children, carrying pots, torn down bags and dilapidated beddings on their heads, walking on the roads and highways that form the infrastructures of the new India are haunting reminders of the masses of displaced people expelled by wars, riots, genocides, and famines. These forced mobilities as expulsions reflect the worst excesses of neoliberal India, rife with caste-class hierarchies.

Deep Inequalities and Indian Society

Note in the backdrop of these images the high-rises and the gated communities that house India’s upwardly mobile classes, the classes that fuel its financial and technological imaginaries. These are the classes that extract the daily labor of the precarious workers. Ironically, also these same classes are quick to catalyze the expulsion of precarious workers when they are turned into threats, by an inversion of empirical evidence (where the actual threats of the infection are largely carried by the upwardly mobile bodies traveling across global borders) and driven by irrational fears.

Authoritarian Repression and State Control

What is the most striking feature of the Indian lockdown is the paradox inherent in the state’s management of COVID-19 (Roy, 2020). Even as the state has decreed Indians to stay indoors, replete with police violence targeting anyone that is seen outside, large crowds of migrant workers are on the streets, walking insurmountable distance to get home. Contrary to the 24/7 propaganda of the strong leader, the state here is weak and ineffective, demonstrating its lack of preparedness in addressing the needs of those at the margins. The poor governance, lack of preparedness, and mismanagement of the crisis are publicly on display, contrary to the propaganda the regime concocts regularly. The absence of careful planning and consideration of the needs of the migrant workers is evident in the absence of infrastructures of care. For instance, transportation facilities following precautionary measures are entirely missing. Similarly, transit-housing arrangements for precarious migrant workers following precautionary measures are entirely missing. Infrastructures for addressing everyday food needs of migrant workers are entirely absent.

All this is ironic in the backdrop of the power asserted by the authoritarian state to mobilize material resources quickly to set up infrastructures for marking and incarcerating so-called illegals picked up by its neo-fascist National Register of Citizens. The precarious workers that hold up the IT-finance economies in the metropole are discardable. Their bodies can be thrown off, disciplined, and violently targeted by the repressive state in its performance of governance. What’s more, as amply evident on our screens, their bodies can be subjected to brutal violence and repression unleashed by the police as instruments of the state. As all this happens, the yuppies from the gated communities that benefit from the labor of these precarious bodies are all too comfortable that the threat has been managed and mitigated. Note the inversion at work here, much like other discourses of inversions carried out by the neoliberal regime. The burden of COVID-19, a virus carried into India by the chains of neoliberal mobility, has to be borne by India’s underclasses. The performance of risk is an inversion of the actual sources of risk.

Depletion of Public Health

The poverty and precarity made visible by COVID-19 is constituted amidst extreme neoliberal reforms pursued by a state aligned with the interests of capital (Dutta, 2016). From the privatization of the telecommunication infrastructures to the privatization of the railways, the current regime is soaked in the worst excesses of the neoliberal ideology. This translates into the large-scale absence of financial infrastructures, welfare resources, food resources, and essential shelter infrastructures to address the needs of those in poverty. For a virus that thrives on mobility, guaranteeing these essential infrastructures is central to managing the epidemic. With the Congress-led neoliberal reforms introduced in the 1990s to the BJP-led accelerated privatization of the Indian economy, the public health infrastructure in India has rapidly dwindled. The systematic attack on the public health infrastructure has been catalyzed by transnational Foundations such as the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, which in the name of addressing the HIV/AIDS epidemic, strategically invested into setting up a privatized management model. The hegemony of the mantra of public-private partnerships categorically dismantled the already minimal public health infrastructures.

Community Organizing at the Margins

In the backdrop of the larger structures of neoliberal organizing of COVID-19 response, both in Kerala and Aotearoa, grassroots community participation in dialogic conversation with a socialist state structure points toward other imaginaries, offering transformative registers for COVID-19 response. These imaginaries are explicitly grounded in community collective agency, depicting the resistive spaces of community life organized in principles of collective care. Aligned with the notion of the “pandemic as portal” (Roy, 2020), the empirically grounded practices of community organizing are constituted in relationship with the structures of the state, both in resistance to the structures of the state and in confluence with state formations. The ongoing negotiations of community response with state structures, practices and policies points to the tensile spaces of power constituted in the relationship between the state and community organizing. Organizing at the community is constituted by the state formation, and simultaneously organizes the state formation. The state structure in both Aotearoa New Zealand and Kerala is a site of ongoing negotiations of power between socialist commitments and neoliberal seductions. Whereas, on one hand, both states exist within a broader neoliberal climate that works by individualizing health care, on the other hand, the party politics in state formation in both Kerala and New Zealand articulates an explicitly socialist commitment to differing degrees.

A People-Centric Route to Rebuild the World From the Global South

One by one

Companies close down.

Life comes to a standstill

Everywhere in the land.

Lords are hardly bothered

Lords of the government are hardly bothered (Andalattu, 1987, as cited in Mannathukkaren, 2013).

As the world grapples with the COVID-19 pandemic these lines written decades ago by Andalattu, who often wrote about communism in Kerala, is of much significance. As Andalattu’s poignant lines reverberated, life has come to a standstill now, and the lords are hardly bothered. The policy responses of some countries to COVID-19 reveal the paramount importance given to fiscal repercussions overlooking the health of its people. The reaction of states to thousands of affected people, dead and people in quarantine lay bare the model that has steered public policies over the last decades: the neoliberal model. COVID-19 has shown us a mirror to our society that the neo-liberal strategies have failed humanity. The divide in life chances between rich and poor is apparent, as poor populations lacking access to health services in standard settings are left most vulnerable during times of the COVID-19 debacle (Ahmed et al., 2020). The cracks in developed nations like the US and the UK are evident as the countries are bracing an unexpected peak in COVID-19 fatalities. Years of austerity and cutbacks in public health care have ruined the healthcare system of many such countries (Malliori et al., 2013; Stuckler et al., 2017). As a by-product of neoliberal procedures across public sector establishments, health care system encounters severe limitations at regular times like understaffing, over workload, low salaries, inadequate working conditions (Selberg, 2013) and hence are not likely to provide the desirable care in a crisis like COVID-19. The pursuit of wealth under the neo-liberal agendas has worsened the COVID-19 crisis and nations ability to tackle it. However, the small state of Kerala in India has shown to the world how putting human lives ahead of profit is critical.

Kerala had dealt with setbacks back to back, from severe floods in 2018 and 2019 to Nipah outbreak, a disease known to have no vaccine developed so far. In India, the first case of COVID-19 was reported in Kerala on January 30th, 2020, when a student who came to Kerala from Wuhan, China contracted the virus (Raghunath, 2020). Kerala with 35.1 million population is a much-touted tourist destination for international travelers and it has a massive number of expatriates who travels back and forth. These posed a risk for transmission among its population. Kerala’s COVID-19 cases escalated in March first week when people started coming back from middle-eastern countries and Europe. At one stage, the state had the maximum number of contagions in India. As of May 9th, 2020, 503 cases were reported in Kerala, and four people died, amounting to <1% of the total reported cases. Whereas, India, in total, has 59,662 cases with 1,981 deaths (PTI, 2020). Kerala was able to flatten the curve because of its stable grass-root democracy and robust healthcare system (Biswas, 2020). The Guardian cites Kerala as an exemplar of COVID-19 response (Kurian, 2020). A Washington Post story states that aggressive testing and contact tracing is key to communist-run Kerala’s triumph in tackling COVID-19 (Masih, 2020).

Socialist Organizing

In this section, we argue that Kerala’s COVID-19 success is an offshoot of years of investment in healthcare and its people-centered development strategy. Kerala tops the human development index, compared to other states in India, and in sharp contrast to the state of Gujarat that is sold as the model of neoliberal growth and development (Singh, 2020). The state has high literacy rates and better health outcomes than other Indian states, with strong state support for education (Tripathi, 2019). Over the years, the Communist Party of India -Marxist [hereafter cited as CPI(M)]-led government has tremendously invested in education and in the healthcare system (Namboodiripad, 1984, 1994; Thomas and Jayesh, 2019; Raj, 2020) to assist the underprivileged sections of the society (Chasin and Franke, 1991). Kerala is one of the few states in India where left parties play an active role in the socio-political environment [other than the state of West Bengal where the CPI(M) has been on a decline because of problems with organizational structure as well as the targeted attacks organized by right-wing reactionary forces]. From the very outset of the first communist ministry in 1957, the left has played an inevitable role in shaping the public discourse and consciousness in Kerala (Singh, 2011). In 1979, a coalition called the Left Democratic Front was created, of which the CPI(M) is the largest political party (Bhatt, 2005). CPI(M) paved a new road to socialist democracy, where the party gave precedence to democratic institutions, practices, and policies in Kerala (Williams, 2017). Despite Kerala’s precarious financial position, state governments of Kerala have never reversed any public service schemes, thus reiterating the commitment of state governments to the social sector (Heller and Isaac, 2005). The rhetoric of the Communist Party is instilled with strong overtones of well-being and CPI (M)’s election manifesto commits to the right to free health care. Under the current communist-led government, an initiative called “Aardram” was launched in Kerala to make public health care system more people-centric and to improve the amenities of public health facilities (Chetterje, 2020), thus slashing the dependence of public on private health facilities. The people centered policy by the left front and the grassroot participation carved a remarkable public health infrastructure for Kerala.

The communist state in Kerala, embedded within a larger democratic electoral politics, is embossed by substantial social expenditures and schemes targeted at the margins of society. Contrary to India’s tryst with neoliberalism, the communist government in Kerala battled the neo-liberal policies encouraged by the Central government (Nair, 2007). Socio-political organizations in Kerala regularly submitted requests to officials for better health and educational facilities (Nag, 1983). Failure to meet public demands caused agitations, in some instance officers were gheraoed or encircled by agitators who did not permit them to leave the office premises until their demands were met (Franke and Chasin, 1992). In the 1970s, CPI(M) employed one of the most radical set of land reforms in the world to safeguard the rights of the tenants on land (Franke and Chasin, 1992). The communist government in 1996 took the agenda of decentralization as the priority and introduced the “People’s Campaign for Decentralized Planning” as a commitment to democratic politics and to amplify the participation of community in planning process (Heller et al., 2007). The solidarity of communist government for class-based movements in Kerala (Heller, 2000) augmented social trust and paved way for many programmes with community participation. Under the communist regime an ascendance of neoliberalism is evident in Kerala, with high rates of unionization (Dreze and Sen, 2002; Thanickan, 2006). Participatory institutions and grass roots democracy under CPI(M) developed a unique state-civil society synergy, synergized in a socialist register to deliver the fundamental resources of health and well-being to the economically dispossessed (Heller, 2000). The aftermath of 2008 financial crisis saw a reduction of investment in public health in many countries including across India; however the investment in state public health infrastructure has been a consistent policy tool of the successive communist governments in Kerala. The “Kerala model of health” is often seen as “good health based on social justice and equity,” rooted in the CPI(M)’s conceptualization of health as a universal human right (Ekbal, 2017).

With adequate capacity built into the state-led health care system, COVID-19 treatment in Kerala focused on delivering care in government hospitals rather than assigning it to private players. For every coronavirus case, a comprehensive route map was created. This was then widely circulated in neighborhoods and social media to find whether other people have been exposed to the virus (Rakesh, 2020). When the virus spread to hundreds, healthcare workers and volunteers with flowcharts conducted rigid contact tracing and thus helped to flatten the curve of community spreading. The community participation was evident when students also chipped in forming walk-in kiosks for taking samples (Varma, 2020). The counter-hegemonic use of spaces and decentralization of power was reflected when village councils enabled community outreach programmes to combat COVID-19 (Sweeney, 2020). This strong community participation was equipped with a strong public education system that had invested in literacy, and especially science literacy. The CPI(M)-associated civil society-led science communication program has invested into building an open science infrastructure across communities in Kerala, anchored in the concept of creating democratic spaces for universal access to scientific literacy.

Regular press meets by the Kerala government kept people well-informed about the situation. The campaign, “Break the Chain” was initiated by the Kerala government to keep people informed about the benefits of washing hands to stop the spread of the virus and thus breaking the chain of community spreading (Bhattacharya, 2020; Flattening the curve: Lessons from Kerala, 2020). A veritable group of volunteers, local government institutions, Kudumbashree, another community initiative, engaged in the production of masks and sanitizers and distribution of foods. Activities ranged from production of over 1,45,000 masks and 2,000 l of hand sanitizers, distribution of food, medicine and so on (Mohan, 2020). These are exemplary examples of workers power, to tackle the crisis of neo-liberalism.

Community Care

The mortalities resulting from COVID-19 has taken a back seat as the state of Kerala was hell-bent in sheltering its population from the catastrophe. On March 19, 2020, a 2.6 billion package was announced by the Kerala government to tackle the pandemic (Agarwal, 2020). Community kitchens, reflecting community care and ownership, were set up to feed the needy. Free treatments were provided to the infected and quarantined people. Regardless of category free rice and other essential items were distributed through ration shops. The government ensured that midday meals will be delivered for school children at their homes and social security pensions for 2 months were given to the elderly (Nowrojee, 2020). Helplines were developed for people struggling to cope with COVID-19 stress and anxiety. The state also was equipped to bring its international migrants who were stranded in different pockets of the world and to provide them medical assistance as needed (Mathew, 2020).

COVID-19 deprived the migrant laborers of their livelihood, who came from rural areas to find work in cities. The neoliberal forces extracted the most from these migrant laborers in the form of cheap labor and during the COVID-19 pandemic they were left on the streets, exposed and vulnerable. Across Indian cities, several incidents were reported where precarious migrant workers were discriminated, marginalized, mistreated and attacked (Dutta, 2020d). The plight of migrant workers in other states were deplorable as they underwent starvation, police violence and they had to walk hundreds of kilometers to their villages from the big cities. Kerala has outshined the rest of India, in handling the plight of migrant workers. Whereas, Kerala has acknowledged that the foundation of Kerala’s infrastructure constitutes the labor of precarious migrant workers from other states. The migrant workers in Kerala, from other states, were given the title of “guest workers,” given proper shelters and provided with food (Why Kerala is a home to ‘outsiders’ – Times of India., 2020). In Kerala, several programmes were launched to help low-wage migrant workers in contrast to other states. The communist led government intervened to lessen the hardships of migrant workers in Kerala, by cash transfer, supplying free rations and food. Out of the 23,567 camps set up for the migrant workers in India, Kerala attributed for 65% (Sadanandan, 2020). The government recognized that the sudden lockdown must have caught the migrant laborers off guard and hence, took the responsibility of them in the time of uncertainty. When the stories of neglected marginalized migrant workers in countries like Singapore are surfacing (Ratcliffe, 2020), the Kerala model, shows how health is intertwined in participation, transparency and voice.

Community-centric approach by Kerala demonstrates that it has disruptive potential to break from the chains of a system embedded in individualism and create a response based on solidarity and compassion. In a world, where humans are devalued, and happiness is measure by wealth and economic growth; such models are pertinent to overcome the neoliberal dogmas. We all need a voice so that we can denounce the callous neglect for human life in the neoliberal regimes. As the so called “global leaders” like the USA, the UK, stands still, there is a clarion call to relook policymaking and regulatory processes and to adopt a people-centric method, which is the most prudent alternative we have amid the COVID-19 crisis.

Maori Organizing in Aotearoa, Power, and Politics

This paper explores Iwi-led checkpoints as a humanitarian, cultural and community response to COVID-19 against the backdrop of the colonial settler state and amidst the politics, police and power structures in Aotearoa, New Zealand. Given the historical accounts of past pandemics in Aotearoa, Māori, particularly in geographically isolated areas, have lived memories of harrowing pandemics that have been passed down through the generations. Māori collectivization to prevent virulent death once again sweeping through their communities was a necessary response. Ngata (2020) contextualizes the Iwi-led checkpoints on the borders of tribal boundaries amidst public criticism, backed by a petition against the checkpoints, created by a far right racist group called Hobson’s Pledge (Dalder, 2019). Ngata (2020) explains the importance of the checkpoints to safeguard isolated communities because “nobody will come to do this for us, and nor could they do it as effectively as us, for nobody knows and loves our people and place as we do (para 8).”

Iwi-Led Checkpoints

Te Whānau a Apanui, located in a geographically isolated area in the Eastern Bay of Plenty, took prompt action to close their borders with Karakia (Prayer) to all who did not reside in the area on 25 March 2020. Waititi (2020), Iwi (Tribal) representative announced the establishment of an Iwi checkpoint citing around 200 Kaumātua (Elders) residing in their Tribal area, sparce medical services and the over 100 km journey to the nearest hospital as compelling factors to exert their sovereignty to look after their own community. There were no COVID-19 cases in the area and the Iwi was committed to keeping the virus locked out. To reduce the travel to supermarket services, also located over 100 km away, Te Whānau a Apanui started an online shopping system providing the community with supermarket food 2 days a week (Paranihi, 2020). Whilst their major food sources are derived from the forest, the ocean and rivers, the government uniformly banned all hunting and fishing. Notwithstanding the ban, Waititi encouraged other Māori communities not to “rely on the government and their supplies to save us” (Waititi, 2020 as cited in Paranihi, 2020, para 11) and continue with their tribal food gathering practices.

The remote community of Te Araroa is a 3 h drive to the nearest hospital in Gisborne. The Iwi also created plans to establish their checkpoint prior to lockdown. Iwi in the Far North, Taranaki, Maketu, and Murupura followed suit (Graham-McClay, 2020; Jones, 2020; New Zealand Herald, 2020; Wright, 2020a). It was the Iwi-led checkpoint in Murupara that attracted the most attention. Two gang members from different gangs joined the frontline Iwi-led checkpoint drawing negative and racist criticism (Judd, 2020 as cited in Hurihanganui, 2020; Ngarewa-Packer, 2020). In response to the racism and cited in Video: Gangs unite with Iwi against COVID-19 (Peters K. N., 2020), Iwi checkpoint organizer, Leila Rewi created a Tiktok video of the checkpoint volunteers—Iwi, Māori from other areas and gang members, united and dancing on checkpoint duty to a song called Tutahi – Stay (Coddington et al., 2020), by a collection of New Zealand artists, innovatively recorded during lockdown level four. The Tiktok video went viral, shared by supporters and critics. Noteably the negative volume on Iwi-led checkpoints increased as Hobson’s Pledge initiated a petition to stop the checkpoints. Conversely an outpouring of support for the checkpoints not just by Iwi members but by general community members gathered momentum (One Double, 2020; Scoop, 2020). The Iwi-led checkpoint at Murupura continued unabated, with frontliners smiling and, or dancing as they exercised their Iwi and community sovereignty. Mongrel Mob member, Deets Edwards explains that:

we weren’t breaking the law, we were out there greeting people with hello. We didn’t physically stand there to force someone to stop. They stopped on their own free will…The people that didn’t know me, like everyone else, they’ll judge a book by its cover (Edwards, 2020 as cited in Wright, 2020b, paras 7–8).

The Iwi-led checkpoints continued to be emphatically discussed in the Epidemic Response Committee’s live online daily meetings, led by the leader of the National Party, Simon Bridges. This committee was set up by the government to scrutinize its national COVID-19 pandemic response. Recounting reports from concerned citizens annoyed that their freedom of movement was being challenged at Iwi-led checkpoints, the committee demanded answers from the Police Commissioner, Andrew Coster about the legality of these checkpoints. Under lockdown level four regulations, everyone was banned from traveling inter-regionally (Small, 2020); but that didn’t stop some people, who attempted travel under the cover of darkness (Canning, 2020; Neilson, 2020).

During the first few weeks of lockdown level four, at the local level, Police supported the checkpoints both conceptually and visibly (Peters K. N., 2020; Peters M., 2020; RNZ, 2020). This was backed by the Deputy Police Commissioner, Wally Haumaha who was keen to model community partnerships with Iwi, particularly in isolated areas (Haumaha, cited in Peters K. N., 2020). Initially, when the Media asked the PM about whether she approved of the checkpoints, described by the Media as “medical checkpoints,” the PM sidestepped the issue and responded generally about self-isolation as evidenced in both the live-update video recordings and the transcriptions of those video recordings uploaded on the official New Zealand government website (New Zealand Government, 2020a). The next time the Iwi-led checkpoints were raised by Media during the PM’s live updates was on day four of lockdown on 29 March 2020. Again, the PM’s response carefully sidestepped referencing “Iwi-led checkpoints,” referring instead to her communication with local MPs from the Iwi area regarding the local establishment of roadblocks (New Zealand Government, 2020b). As criticism mounted in some sectors regarding the legality of the Iwi-led checkpoints, the PM was further questioned about her stance on the checkpoints almost 1 month later on 22 April 2020. The PM indicated that the Police have been working with communities to ensure that the checkpoints are conducted within the law, strategically keeping the focus on the intent and response of communities to safeguard each other. An acknowledgment from the PM that the checkpoint initiatives from these communities were Iwi-led was still not forthcoming (New Zealand Government, 2020c). The next day on 23 April 2020, the verbatim was not that different, except the PM highlighted that the powers to stop people lay only with the Police and the Civil Defense (New Zealand Government, 2020d).

New Police Commissioner, Coster (2020) followed suit by carefully avoiding the phrase “Iwi-led checkpoints,” in his article, referring to them instead as “COVID-19 community checkpoints,” or “community-led checkpoints” devaluing the stoic, around the clock labor actioned by Iwi in placing their bodies on the line to prevent the spread of COVID-19 amongst their Whānau, Hapu, Iwi and communities. Moreover, Coster added that “a strong enforcement-led response to the [Iwi] checkpoints could lead to protests at various sites around the country…” (Coster, 2020, para 9). Iwi members gathering and protesting at various sites around the country during lockdown level four would disrupt the lockdown plan and not align with the government’s messaging that “we are all in this together.” Coster added that the model of policing underscored by the principle of discretion directed Police action by deploying Police to Iwi-led checkpoints in a monitoring capacity to both ensure that public movement is lawful and within the lockdown restrictions. Notably, the discretion principle that underpins the policing model referred to by Coster was not utilized during the latter half of 2019 when the Police presented in considerable numbers at Ihumātao to restrict the movement of the land protectors occupying the land (Webb-Liddall, 2019). The communication strategy adopted by the PM and the Police Commissioner rendered taboo the mere mention of “Iwi-led checkpoints” in their media statements, preferring instead the referencing of “community checkpoints.” Whilst there were reports of community volunteers assisting at the Iwi-led checkpoints, these care initiatives were, as the name clearly describes, led by Iwi. Yet an examination of the transcriptions reveal that the government had no qualms about referencing Iwi when Iwi were assisting Civil Defense teams to distribute food among vulnerable communities and collaborate with agencies to secure housing assistance (New Zealand Government, 2020d). When the pulse of racism quickens to sideline Iwi sovereignty, exacerbated by negative public opinion, the government’s mantra that “we are all in this together” during the COVID-19 pandemic reveals the entrenched logics of acceptable participation determined by this nation’s hegemonic, colonial power structures.

Ironically, while some of New Zealand’s concerned citizens together with National and Act Party members on the Epidemic Response Committee were challenging the legality of the Iwi-led checkpoints, a judicial review application challenging the legality of some of the lockdown orders was before the High Court. In Christiansen v. The Director-General of Health (2020), the applicant, Oliver Christiansen returned to New Zealand to visit his dying father in April 2020. Christiansen was confined to managed isolation but when his father’s illness suddenly declined, Christiansen sought an exemption to the order issued under the Health Act 1956, as a matter of urgency, to enable him to visit his father. Ministry of Health officials acting under delegated authority by the Director-General, Dr. Ashley Bloomfield declined Christiansen’s application. The High Court upheld Christiansen’s application and overruled the government’s COVID-19 lockdown orders (Hurley and Bayer, 2020). The High Court ruled that according to the Order provisions, the Ministry of Health was wrong in denying Christiansen an early exemption out of mandatory lockdown to visit his father. Christiansen was able to visit his father 1 day before he passed away. Subsequently Jacinda Ardern, prime minister ordered a review into all the Ministry of Health decisions on this matter.

Former Parliamentary Counsel, Andrew Borrowdale is also seeking a judicial review by the High court to determine whether the government was sufficiently empowered by legislation to enact lockdown levels four and three. Chair of the Epidemic Response Committee, Simon Bridges has tagged onto the legal debacle and is planning to tackle parliamentary privilege to summon government officials and parliamentary privilege to obtain all legal advice received by the government to enact lockdown to determine if the government acted within its powers (Geddis, 2020; Geiringer, 2020; RNZ, 2020). Obtained via public official information requests, thousands of official COVID-19 government papers were released on 8 May 2020 revealing the basis for the government’s COVID-19 decisions (Walls and Cheng, 2020), except for the legal advice documents.

Discussion

One of the key threads that emerges from the community organizing in response to COVID-19 is the nature of organizing work as political. Interrogating and disrupting the depoliticization of communities to be incorporated into community-based participatory projects serving the agendas of capital, community organizing at the margins in the Global South/South in the North foreground the concept of community sovereignty. Community sovereignty, moves beyond the concept of community mutual aid in support of each other, to organizing communities to resist local-global structures of individualization and privatization under the hegemonic neoliberal project (Dutta, 2016). Organizing processes and structures of pandemic response, owned by those at the “margins of the margins” in communities challenge the hegemonic theorizing of pandemic response that construct the prevention of the pandemic in terms of behavior change (constructing individuals in the dichotomous category of adherence/non-adherence).

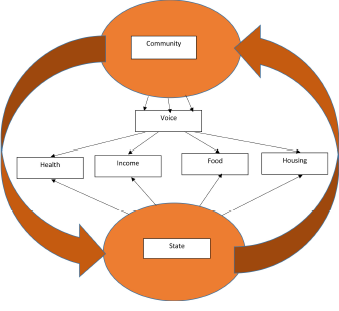

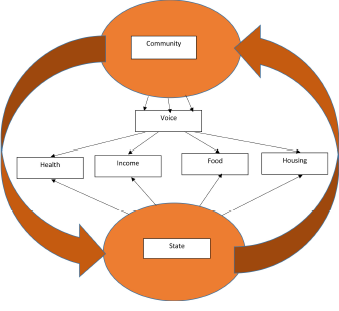

In resistance to a top-down definitional framework that sees behavior change as individual response produced through persuasive messages (Dutta, 2005), community sovereignty foregrounds and renders visible the structures of inequality that are exacerbated and worked upon by the pandemic, constituting the contexts within which behaviors are enacted. Health behavior, in this case COVID-19-related behaviors, Therefore, in the two cases offered in this article, when the very structural formations that constitute behaviors are targeted, health communication works toward structural transformation that enables collective preventive behaviors at the community level. In addition, community organizing is directed specifically at addressing the overarching structures, thus directly addressing the health needs at the margins and seeking to transform overarching pandemic inequalities. Based on these two cases, we attend to the interplays of community and state structures in constituting pandemic response, mediated through voice (see Figure 1). Voices of the margins laying claims to infrastructures of health, education, income, and food interact with the state, both constituted by the state and in turn, constitutive of it. Drawing on the key conceptual tenets of the CCA, we thus propose a strong state for pandemic response that is simultaneously centralized and de-centralized. As opposed to the extreme neoliberal state that is “rolled out” to serve capital while simultaneously being “rolled back” from the delivery of essential health and well-being infrastructures, the culture-centered state is strengthened in its capacity to deliver substantive health and well-being infrastructures through the participation of the “margins of the margins.”FIGURE 1

Figure 1. Community-state interaction in constituting COVID-19 response.

In India, the community response in Kerala is situated within a socialist structure of organizing politics and economics, with the strong presence of worker organizing and the transformative role of the CPI(M). The specific forms of welfare and workplace protections secured in the state through the ongoing organizing of unions and collective movements serve as the basis of developing a COVID-19 response that is directed at addressing the entrenched structural inequalities. The recognition of structural violence as the conduit through which the pandemic spreads, the community organizing work complements the structurally-directed intervention designed by the CPI(M). Drawing on the deep roots of grassroots organizing, land reforms and resource distribution that form the architectures of the CPI(M), community organizing works alongside Left party politics to materialize a socialist framework of pandemic response. The community response in Kerala is constituted by the state policy directed at decentralization and community-led governance. Contrast the Kerala model with the pandemic response across India formulated within a neoliberal framework, without protection for the poor and the working classes, expelling migrant workers into conditions of vulnerability, and without the provision of fundamental resources of health and well-being (Roy, 2020). Moreover, contrast the Kerala model of a strong education infrastructure with robust science literacy in the backdrop of a weak education and science infrastructure across large cross-sections of neoliberal idea, with the ruling Hindutva forces being key players in the dissemination of misinformation. The strong scientific temperament in community networks in Kerala stands in contrast to the communicative structures of disinformation and superstition disseminated by Hindutva forces across India.

In Aotearoa, iwi-led checkpoints, grounded in the voices and actions of grassroots Whānau, Hapu, and Iwi, foreground the concept of community sovereignty (tino rangatiratanga) in the backdrop of a settler colonial state. Through sovereignty, communities take collective ownership of households, families, and larger collectives, anticipating and addressing the deep inequalities that are likely to impact disproportionately communities at the margins. The larger racist responses to iwi-led checkpoints, particularly from the right (National Party, center right), using the language of law and order, depict the ways in which transformative community participation challenges the hegemonic formations of colonial-capitalist state structures. Through their participation in organizing responses to the pandemic that assert materialities of boundary-making to protect community health and well-being, iwi-led checkpoints write new possibilities for organizing global health and well-being. The organizing of community voice is constituted amidst the Te Tiriti O Waitangi (Treaty of Waitangi) that offers a framework for making Māori claims into the colonial state. The Treaty itself emerges in the discursive-material arena as a register for challenging the catalytic expansion of neoliberalism. Moreover, the check-point response is constituted amidst a center-Left Labor-led government that has offered a strong centralized response to the pandemic, driven by science and addressing the economic needs of those hit by the lock-down. Particularly salient in Labour’s response to the pandemic are clear communication and the overarching narrative of kindness that shaped the response to the pandemic. Māori community sovereignty is negotiated in dialogue with a state that is currently turning toward a rights-based response in contrast to the earlier capital-friendly leadership of the National Party (Note here that the neoliberal reforms were initiated into New Zealand by Labor and pursued aggressively subsequently by National Party as well as Labor). Foregrounding the logics of community sovereignty in global responses to COVID-19 recognizes community agency as the basis of pandemic response. Community participation in this instance, rather than being directed and scripted by the colonial state to fit pre-existing colonial agendas, emerges as a site of owning community health and well-being. Voices reflecting Māori agency exist in ongoing negotiations of power with the colonial state, foregrounding the vitality of Māori party formations in shaping state responses. Simultaneously, given the large scale health disparities experienced by Māori in New Zealand, these party formations ought to be fundamentally anchored in commitments to securing universal rights to basic income, housing, food, education, and health.

In summary, the culture-centered processes of community organizing drawn on the case studies of community organizing in Communist Kerala and in iwi-led Māori checkpoints in settler colonial Aotearoa New Zealand foreground the vital work of alternative4 practices of health response, serving as the basis for robust alternative imaginations amid the pandemic. Both of these contextually situated frameworks of pandemic response recognize and work with a radical conceptualizing of community organizing, owned by the “margins of the margins” as the basis of transforming the deep inequalities that threaten human health and well-being, and that have been rendered visible by the pandemic. Compared to the failed neoliberal responses elsewhere across the globe, we point to the exceptional success of the Kerala model and the Māori model. The exceptionalism of these models offers an imaginary anti-dote to exceptional neoliberalism that has worked over the last three decades by turning the structural and material violence of neoliberalism into the normative mode of global governance. The interplays of socialist organizing and community democracy materially evident in the cases discussed here dismantle the neoliberal ideology that constitutes the exceptional violence evident globally amidst the pandemic, both as a result of the pandemic as well as a result of the market-driven policy responses to pandemic. The very processes of community participation that co-opt community agency into serving the neoliberal status quo are organized in resistance in these two instances, thus challenging the various forms of erasure written into hegemonic processes of knowledge production and health response. Cultural centering is the turn toward communities as spaces for challenging structures and building communicative equality through grassroots democracy. Co-creating infrastructures for community voices centers grassroots democracy while simultaneously re-organizing the state in socialist principles to ensure fundamental access to education, income, housing, food, health and well-being. Although the two examples offered here provide openings for building democratic socialist pandemic responses, more broadly, they offer global registers for re-organizing health, education, housing, food, and income. Drawing on Roy’s (2020) invitation to work through the “pandemic as a portal,” our analysis of community organizing in Kerala and community-led Māori checkpoints in Aotearoa New Zealand puts forth a conceptual register for addressing COVID-19 transitions, as well as for organizing post-COVID political economies. Ultimately, communicative equality as the basis for health communication is constituted in ongoing dialogue between community agency and state response, seeking to building infrastructures for voices of the “margins of the margins” and simultaneously creating a socialist state.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

All authors have conducted literature review, participated in theorizing, and written part of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the Center for Culture-Centered Approach to Research and Evaluation (CARE).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

1. ^The culture-centered approach (CCA) constructs communities as contested, dynamic, and unequal terrains, constituted in relationships of power. Communities are sites of interrogating power as well as creating radical equality through struggles for power. Interrogating the hegemonic notion of the community as monolith, the CCA suggests that communities are strategically constructed, crafting specific identities directed toward achieving certain goals. In culture-centered co-constructions with the margins, communities are depicted as spaces at the margins, forged through communicative processes to articulate demands.

2. ^The concept of the “margins of the margins” reflects the processes of discursive erasure and material marginalization constituted in community organizing spaces in marginalized contexts. As a theoretical, methodological and practical anchor, the “margins of the margins” point toward the vitality of collective reflexivity as the basis for continually attending to erasure and the necessity for building communicative equality that is open-ended.

3. ^In constructing the cases, we will draw from published news reports, reports by civil society organizations, as well as academic reports.

4. ^The very notion of “alternative” is constituted in relationship to the neoliberal model. In this article, we hope that these alternatives emerge as pathways to the mainstream in post-COVID organizing.

References

Agarwal, S. (2020, May 2). This state in India shows us why fighting COVID-19 requires working-class power. Truthout. Available online at: https://truthout.org/articles/this-state-in-india-shows-us-why-fighting-covid-19-requires-working-class-power/

Ahmed, F., Ahmed, N., Pissarides, C., and Stiglitz, J. (2020). Why inequality could spread COVID-19. Lancet Public Health 5:e240. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30085-2

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Basu, A., and Dutta, M. J. (2009). Sex workers and HIV/AIDS: analyzing participatory culture-centered health communication strategies. Hum. Commun. Res. 35, 86–114. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2958.2008.01339.x

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Bhatt, S. C., and Bhargava, G. K. (2005). Land and People of Indian States and Union Territories: (in 36 volumes). New Delhi: Gyan Publishing House.

Bhattacharya, S. (2020, March 16). Kerala launches break the chain handwashing campaign in light of coronavirus pandemic. Republic World. Available online at: https://www.republicworld.com/india-news/general-news/kerala-launches-break-the-chain-handwashing-campaign-against-covid-19.html

Biswas, S. (2020, April 16). How India’s Kerala state ‘flattened the curve’. BBC News. Available online at: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-52283748

Brenner, N., Peck, J., and Theodore, N. (2010). Variegated neoliberalization: geographies, modalities, pathways. Glob. Netw. 10, 182–222. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0374.2009.00277.x

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Cammaerts, B. (2020). The neo-fascist discourse and its normalisation through mediation. J. Multicult. Discourses 15, 1–16. doi: 10.1080/17447143.2020.1743296

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Canning, R. (2020, April 7). Turangi population swells, bach owners arrive in dead of night. NZ Herald. Available online at: https://www.nzherald.co.nz/rdp-taupo-turangi/news/article.cfm?c_id=1503734&objectid=12323243

Chapple, S. (2016). New Zealand’s first recorded post-contact epidemic: untangling the tale of Rongotute and Te Upoko o Rewarewa. Archaeol. N. Zeal. 21–32.

Chapple, S. (2018). Death and Disease at the Dawn of New Zealand’s History. ResearchGate. Available online at: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Simon_Chapple5/publication/327427166_Death_and_disease_at_the_dawn_of_New_Zealand’s_history/links/5b8ee7e7299bf114b7f60bfd/Death-and-disease-at-the-dawn-of-New-Zealands-history.pdf

Chasin, B. H., and Franke, R. W. (1991). Kerala state, India: Radical reform as development. Month. Rev. 42:1. doi: 10.14452/MR-042-08-1991-01_1

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Checkpoint (2020, March 26). Covid-19: Does NZ have enough ICU beds, ventilators? RNZ. Available online at: https://www.rnz.co.nz/national/programmes/checkpoint/audio/2018740328/covid-19-does-nz-have-enough-icu-beds-ventilators

Chetterje, P. (2020). Gaps in India’s preparedness for COVID-19 control. Lancet Infect. Dis. 20:544. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30300-5

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Christiansen, v. The Director-General of Health (2020). NZHC. 887. Available online at: https://courtsofnz.govt.nz/assets/cases/Christiansen-v-The-Director-General-of-Health-Reasons-NZHC-887.pdf

Coddington, A., Wiley, B., Smith, H., Hall, R., Theia Kora, F., et al. (2020, April 14). Tutahi – Stay [Official Music Video]. Available online at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rVhd21jpjGQ

Coster, A. (2020, May 4). Coronavirus: Iwi checkpoints were about safety and discretion. Stuff. Available online at: https://www.stuff.co.nz/national/health/coronavirus/121400826/coronavirus-iwi-checkpoints-were-about-safety-and-discretion

Dalder, M. (2019, February, 2). The furious world of New Zealand’s far right nationalists. Spinoff. Available online at: https://thespinoff.co.nz/politics/31-12-2019/summer-reissue-the-furious-world-of-new-zealands-far-right-nationalists/

Day, A. (1999). ‘Chastising its people with scorpions:’ Māori and the 1913 smallpox epidemic. N. Zeal. J. Hist. 33, 180–199.

PubMed Abstract | Google Scholar

Dreze, J., and Sen, A. (2002). India: Development and Participation. Oxford University Press on Demand.

PubMed Abstract | Google Scholar

Dutta, M. J. (2004). The unheard voices of Santalis: communicating about health from the margins of India. Commun. Theor. 14, 237–263. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2885.2004.tb00313.x

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Dutta, M. J. (2005). Theory and practice in health communication campaigns: a critical interrogation. Health Commun. 18, 103–122. doi: 10.1207/s15327027hc1802_1

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Dutta, M. J. (2007). Communicating about culture and health: theorizing culture-centered and cultural sensitivity approaches. Commun. Theory 17, 304–328. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2885.2007.00297.x

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Dutta, M. J. (2008). Communicating Health: A Culture-Centered Approach. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Dutta, M. J. (2011). Communicating Social Change. Structure, Culture and Agency. New York, NY: Routledge.

PubMed Abstract | Google Scholar

Dutta, M. J. (2013). Public relations in a global world: culturally centering theory and praxis. Asia Pac. Public Relat. J. 14, 21–31.

Dutta, M. J. (2015). Decolonizing communication for social change: a culture-centered approach. Commun. Theor. 25, 123–143. doi: 10.1111/comt.12067

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Dutta, M. J. (2016). Neoliberal Health Organizing: Communication, Meaning, and Politics. New York, NY: Routledge.

Dutta, M. J. (2017). Migration and health in the construction industry: culturally centering voices of Bangladeshi workers in Singapore. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 14:132. doi: 10.3390/ijerph14020132

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Dutta, M. J. (2018). Culture-centered approach in addressing health disparities: communication infrastructures for subaltern voices. Commun. Methods Meas. 12, 239–259. doi: 10.1080/19312458.2018.1453057

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Dutta, M. J. (2019). What is alternative modernity? decolonizing culture as hybridity in the Asian Turn. Asia Pac. Med. Educ. 29, 178–194. doi: 10.1177/1326365X19881256

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Dutta, M. J. (2020a). “Culture-centered community-led testing,” in CARE White Paper (Palmerston North: Center for Culture-Centered Approach to Research and Evaluation).

Dutta, M. J. (2020b). “A culture-centered approach to pandemic response: voice, universal infrastructure, and equality,” in CARE White Paper (Palmerston North: Center for Culture-Centered Approach to Research and Evaluation).

Dutta, M. J. (2020d). COVID-19: India’s underclasses and the depravity of our unequal societies. The Citizen. Available online at: https://www.thecitizen.in/index.php/en/NewsDetail/index/4/18516/COVID19—-Indias-Underclasses-and-the-Depravity-of-Our-Unequal-Societies

Dutta, M. J. (2020e). “Infrastructures of housing and food for low-wage migrant workers in Singapore,” in CARE White Paper (Palmerston North: Center for Culture-Centered Approach to Research and Evaluation).

Dutta, M. J., and Basu, A. (2008). Meanings of Health: Interrogating structure and culture. Health Commun. 23, 560–572. doi: 10.1080/10410230802465266

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Dutta, M. J., and de Souza, R. (2008). The past, present, and future of health development campaigns: Reflexivity and the critical-cultural approach. Health Commun. 23, 326–339. doi: 10.1080/10410230802229704

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Dutta, M. J., Pandi, A. R., Mahtani, R., Falnikar, A., Thaker, J., Pitaloka, D., et al. (2019). Critical health communication method as embodied practice of resistance: culturally centering structural transformation through struggle for voice. Front. Commun. 4:67. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2019.00067

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Dutta, M. J. (2020c). “Structural constraints, voice infrastructures, and mental health among low-wage migrant workers in Singapore: solutions for addressing COVID-19,” in CARE White Paper (Palmerston North: Center for Culture-Centered Approach to Research and Evaluation).

Ekbal, D. B. (2017). Kerala Model of Health: From Success to Crisis. The New Indian Express. Available online at: https://www.newindianexpress.com/states/kerala/2017/aug/14/kerala-model-of-health-from-success-to-crisis-1642904.html

Flattening the curve: Lessons from Kerala. (2020, May 6). Punch Newspapers. Available online at: https://punchng.com/flattening-the-curve-lessons-from-kerala/

Franke, R. W., and Chasin, B. H. (1992). Kerala state, India: radical reform as development. Int. J. Health Serv. 22, 139–156. doi: 10.2190/HMXD-PNQF-2X2L-C8TR

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Geddis, A. (2020, March 25). How politics, police and power work in lockdown New Zealand. The Spinoff. Available online at: https://thespinoff.co.nz/politics/25-03-2020/how-politics-police-and-power-work-in-lockdown-new-zealand/

Geiringer, C. (2020, May 6). Was covid-19 lockdown legal? Professor Claudia Geiringer explains. RNZ. Available online at: https://www.rnz.co.nz/national/programmes/checkpoint/audio/2018745408/was-covid-19-lockdown-legal-professor-claudia-geiringer-explains

Graham-McClay, C. (2020, March 23). New Zealand’s Māori tribes set up checkpoints to avoid ‘castrophic’ deaths. The Guardian. Available online at: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/mar/24/new-zealands-Maori-tribes-set-up-checkpoints-to-avoid-catastrophic-coronavirus-deaths/

Gustafsson, J. E. (2018). Bentham’s binary form of maximising utilitarianism. Br. J. History Philos. 26, 87–109. doi: 10.1080/09608788.2017.1347558

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Habersaat, K. B., Betsch, C., Danchin, M., et al. (2020). Ten considerations for effectively managing the COVID-19 transition. Nat. Hum. Behav. 4, 677–687. doi: 10.1038/s41562-020-0906-x

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Heller, P. (2000). Degrees of democracy: some comparative lessons from India. World Polit. 52, 484–519. doi: 10.1017/s0043887100020086

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Heller, P., Harilal, K. N., and Chaudhuri, S. (2007). Building local democracy: evaluating the impact of decentralization in Kerala, India. World Dev. 35, 626–648. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2006.07.001

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Heller, P., and Isaac, T.T. (2005). “The politics and institutional design of participatory democracy: lessons from Kerala, India,” in Democratizing Democracy: Beyond the Liberal Democratic Canon, eds B. D. Santos (London: Verso), 405–446.

Hickey, B. (2020, March 14). We must go hard and we must go early. Newsroom. Available online at: https://www.newsroom.co.nz/2020/03/14/1083045/we-must-go-hard-and-we-must-go-early

Hurihanganui, T. A. (2020, May 1). MPs’ questioning of legal iwi checkpoints ‘really is racism.’ RNZ. Available online at: https://www.rnz.co.nz/news/te-manu-korihi/415617/mps-questioning-of-legal-iwi-checkpoints-really-is-racism