CARE’s end-of-year address from Professor Mohan J Dutta, Dean’s Chair and Director of CARE via YouTube and Facebook.

Link to Facebook : https://www.facebook.com/CAREMassey/videos/891000409006859

Center for Culture-Centered Approach to Research and Evaluation

CARE’s end-of-year address from Professor Mohan J Dutta, Dean’s Chair and Director of CARE via YouTube and Facebook.

Link to Facebook : https://www.facebook.com/CAREMassey/videos/891000409006859

Check out CARE’s Māra Kai Project – Potatoe planting work continuing in Feilding

Presented by Selina Metuamate.

Facebook : https://www.facebook.com/CAREMassey/videos/6832398133475425

Join us for Professor Cherian George’s Public Talk at the Business Studies (Central) Building, Massey University, BSC B1.08 COMMS Lab. Or join us virtually via the Livestream on our social media platforms.

Facebook Page: https://www.facebook.com/CAREMassey/videos/310113508573077

CARE YouTube Channel: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rXwelom8Ac4

The norms and institutions of democracy and human rights are on the back foot around the world. They clearly need to be strengthened. This work has been disrupted and delayed not only by democracy’s opponents but also from within. There are recurring, divisive debates within liberal democracies concerning how much society should tolerate discriminatory speech. This talk searches for guideposts to navigate the contested terrain between free speech and social justice.

Cherian George is a professor of media studies at Hong Kong Baptist University’s School of Communication, and the director of its Centre for Media and Communication Research. His books include Hate Spin: The Manufacture of Religious Offence and its Threat to Democracy (2016); and Red Lines: Political Cartoons and the Struggle against Censorship (2021).

In Dr. Usman Afzali’s talk, “Long-term Effects of Far-Right Terrorism on Muslims in New Zealand,” the enduring consequences of far-right terrorism on the Muslim community in New Zealand are explored. Drawing upon a comprehensive array of scholarly papers and research from the New Zealand Attitudes and Values Study, the presentation investigates the complex dynamics between far-right violence, public attitudes, and the psychological well-being of Muslim minorities. It reveals how far-right terrorism can lead to national distress, affecting community cohesion and overall well-being. Public attitudes toward Muslims in New Zealand, especially following a terrorist attack, are examined, alongside the role of national identity, media influence, and the potential mitigating role of religion. Usman Afzali’s talk offers a comprehensive understanding of the multifaceted impact of far-right terrorism on Muslims in New Zealand, with implications for future research and policy considerations.

Dr. Usman Afzali is the principal investigator of the Muslim Diversity Study, currently working as a postdoctoral research fellow and lecturer at the University of Canterbury in Christchurch, New Zealand. The Muslim Diversity Study examines social attitudes and values of Muslims in New Zealand. Usman’s research interests encompass human flourishing, diversity in religious groups, cognitive psychology (specifically memory suppression), and contemplative neuroscience.

In the Muslim Diversity Study, he leads a team of 24 research assistants and actively collaborates with numerous partners within New Zealand. Additionally, he conducts research in cognitive psychology and neuroscience, and supervises graduate students at various levels (PhD, Masters, and Honours) since 2021. His teaching portfolio includes courses in statistics, research methods, cognitive psychology, and neuroscience.

Website: https://www.usmanafzali.com

Twitter: @UsmanAfzali

All attendees are invited to NCA Scholars’ Office Hours on Friday, Nov. 17, from 2 to 3:15 p.m. at the Gaylord National Harbor Convention Center.

This annual session provides seasoned scholars, junior scholars, and graduate students the opportunity to network and connect with each other in an informal and interactive atmosphere focused on mentorship. Participants can also meet the current NCA journal editors at the session.

Keeping with the convention’s theme – “Freedom” – this year’s Scholars’ Office Hours expands what it means to be a “senior” scholar in the field of Communication. Participants can expect to meet and speak with scholars who are well-published and advanced in their careers.

At the same time, the session will center scholars who advance community-engaged scholarship, activism, and other non-traditional communication work. We are thinking specifically of scholars who “free up” or open the discipline to new ways of thinking and doing communication work, thereby pushing the discipline forward in transformative ways.

We have assembled an eclectic and diverse group of scholars who cut across multiple areas of the field. To see the full list of participating senior scholars, visit NCA Convention Central.

If you are a graduate student, new tenure track faculty member or adjunct faculty member, you are especially encouraged to attend! We are particularly excited to welcome Black, Indigenous, and early career scholars of color, LGBTQI scholars, and scholars negotiating different abilities working at diverse intersections.

If you have any questions about the program, please feel free to reach out to co-planners Mohan Dutta and Rebecca de Souza. We are excited for you to join us and start networking!

Mohan Dutta, Scholars’ Office Hours Co-planner, Massey University, New Zealand

Rebecca de Souza, Scholars’ Office Hours Co-planner, San Diego State University

CARE: Center for Culture-Centered Approach to Research and Evaluation congratulates its Director, Professor Mohan J. Dutta, Massey University for being named in the latest World’s Top 2% Scientists List (Stanford University). The excellence in the research impact at CARE is reflective of the contributions of our collective of community advisory groups, community researchers, activists-in-residence, and academic research teams working tirelessly to build strong communities as participants in organizing for social change.

We are proud of this recognition of excellence that speaks to the impact our collective scholarship makes to the theorizing of justice-based health communication processes, demonstrating the power of culture-centered community-based communication organizing for social change in transforming colonial, capitalist, patriarchal, racist and casteist structures.

Check out the Dataset- https://elsevier.digitalcommonsdata.com/data…/btchxktzyw/4

Photo by Vivien Beduya.

#ElsevierBV #CAREMassey #WorldsTopScientistsList #CultureCenteredApproach #CommunityBasedCommunication #SocialChange #HealthCommunication #StanfordUniversity #CARECCA #MasseyUni

Join us online and celebrate the many accomplishments featured in the CARE documentary.

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/CAREMassey/videos/3699987516946842

https://www.massey.ac.nz/about/news/care-to-celebrate-10-year-anniversary-with-conference/

On this Gandhi Jayanti, reflecting on the ways in which Gandhi’s experiments with truth resist and challenge the communicative infrastructure of deception that forms the discursive basis of the fascist politics of Hindutva.

“As a fascist ideology, Hindutva thrives on the production and circulation of lies, continually at work to vilify India’s Muslim minorities.

This deception, communicating contradictory and conflicting messages internally and externally, actively producing misinformation, and mobilizing violence on the basis of the misinformation, lies at the crux of the organizing of hate as a technique for rule.

Deception forms the everyday habits of Hindutva, drawing from the Brahminical hierarchy that gives it its conceptual formation. Brahminism as the underlying feature of Hindutva mobilizes the practices of deception.

From the active production of disinformation in the form of conspiracy theories to practices based on lies in everyday life, the communicative infrastructure of Hindutva thrives on deception.”

This article first appeared on the culture-centered blog.

Professor Mohan Dutta, Dean’s Chair Professor of Communication and the Director of the Center for Culture-centered Approach to Research and Evaluation (CARE) will deliver the 2023 G. Jack Gravlee endowed lecture in the Department of Communication Studies at Colorado State University on September 19, 2023.

Professor Dutta’s lecture, titled “Decolonization as organizing radical democracies: Centering health, resisting climate colonialism, securing food systems, and resisting hate” will be delivered in conversation with the University’s theme this coming year (2023-2024), Democracy and Civic Engagement.

The lecture will draw upon two decades of ethnographic fieldwork carried out by Mohan Dutta in struggles for Indigenous rights, migrant rights, transgender rights, anti-racism, and working-class politics, exploring the everyday habits of democracy that are sustained through community action.

The talk will outline the key tenets of the culture-centered approach as an organising framework for decolonizing democracies, attending to Indigenous, Black, and various Global South traditions for organising democracies. It will attend to the ways in which white supremacy shapes the infrastructures of settler colonial/postcolonial/neocolonial democracies, with hegemonic notions of democracy scripted into practices of extraction, expulsion, and displacement through the mobilisation of violence.

Professor Dutta will wrap up the talk by offering insights into the organising work of building transformative democracies through the co-creation of community voice infrastructures that work toward achieving the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, addressing the challenges of climate colonialism, food insecurity, poverty, and digital colonialism.

Professor Mohan Dutta delivers Gravlee Lecture at Colorado State University

By Professor Mohan Dutta

Wednesday 30 August 2023

This opinion piece is the fourth of a five-part series on the intertwined webs of the far-right mobilised to attack communication and media studies pedagogy. This piece is written in solidarity with other communication and media studies academics, researchers, and practitioners who have been targeted by the far-right.

The far-right’s reactionary culture war, cooked up by the Trump-Bannon-Infowars-Fox infrastructure, materialised by extremist groups such as Proud Boys, and legitimised by the right-wing political machinery, has been and will continue to be vigorously resisted by academia.

The Cambridge Analytica whistleblower Christopher Wylie testified to the role of Bannon who, “saw cultural warfare as a means to create enduring change in American politics,” in shaping the strategy of gathering and leveraging information about 87 million Facebook users to drive Trump’s hate-based political campaign. Critical to the campaign was the targeting of African-American communities promoting voter disengagement, and collaborating with Russian intelligence services.

In three earlier essays crafted for this series, I have discussed exactly how the United States-far-right’s culture war is mimicked here in Aotearoa by the right-wing ecosystem working incessantly to pump out fear as an organising tool, as a photocopy of Bannon’s political strategy of deploying hate as a marketing tool. The manufacturing of a culture war as a strategic issue generates leverage, and more specifically votes, for right-wing political parties while simultaneously working to disenfranchise communities at the margins.

I have also outlined how these attacks are directed at silencing academic voices, particularly those working on issues of social justice, disinformation, and hate. Although academics are often the direct targets, the ultimate goal of the far-right is to silence the voices of the marginalised communities we partner with. The force of the attacks is particularly violent when directed at those of us in academia who engage in public scholarship.

In this piece, I will turn to strategies for countering the far-right and outline some of the powerful ways in which academics are resisting these targeted hate campaigns across the globe. Because the far-right’s cancel culture originates from the hate ecosystem linked with Donald Trump in the US, I will also draw upon US-based examples of academic resistance as instructive lessons.

Holding institutional processes accountable

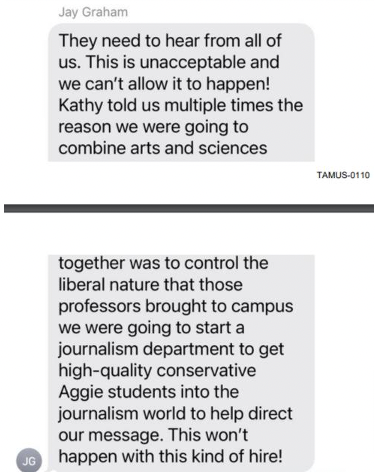

When brilliant Black journalism educator and former editor of the New York Times, Professor Kathleen McElroy, was appointed to lead the new journalism programme at Texas A&M University, the fringe far-right organised a campaign targeting her because of her history of promoting diversity. A conservative website seeded the campaign, building the “DEI (diversity, equity, and inclusion) hysteria” around the hiring of Professor McElroy.

The various pressures from these outside forces, mediated through the interference from the Regents, tampered with the university’s hiring process, resulting in Professor McElroy’s offer being altered, with multiple iterations walking back the tenured position initially offered.

The attacks were organised amidst the Republican Governor of Texas, Greg Abbott, signing a bill attacking DEI offices at public colleges, one among similar such concerted policies introduced by Republican lawmakers across the US. Note here that these fringe policies are built around the “Woke culture” and “Critical Race Theory (CRT)” frenzy that has been concocted by the far-right as political fodder, as a direct offshoot of Bannon’s political strategy of mobilising culture war as a campaign tool. As I have noted earlier, this hysteria around CRT is networked, traveling from the Trumpian ecosystem to the far-right ecosystem in Europe to Australia to Aotearoa.

The targeted campaign, materialised through the interference by the Regents and a timid administration lacking leadership, led to several institutional processes being violated.

A story published in the Texas Tribune first revealed these process violations and the change in the job offer to Professor McElroy. The story was picked up nationally, covered by major news media.

Responding to the events, the A&M Faculty Senate Executive Committee called for the Chancellor to meet with the full Faculty Senate to discuss political influence in faculty matters. The Faculty Senate met with then-President Katherine Banks, asked questions about the botched hiring, and initiated an investigation. An internal report examining the hiring process outlined several violations that took place during the appointment process.

Leaders of the Black Former Student Network wrote to the University System Chancellor John Sharp, saying:

“How this University treated this respected, honored, qualified, experienced, successful, and tenured fellow Aggie is unacceptable and would have been unthinkable yet for her race and gender… The fact that this University outwardly promotes very laudable principles in the Aggie Core Values, yet you don’t have the character nor the courage to follow these Core Values as the leader of this University reveals the deep chasm between your words and your actions.”

The fiasco led to the president’s resignation. The university separately settled with Professor McElroy for US$1 million and she stayed in her position at the University of Texas, Austin. The Texas A&M leadership released a statement, apologising “for the way her employment application was handled.”

In the backdrop of the organised campaigns of the far-right, coupled with the large-scale neoliberal transformations of universities that have foisted an overarching professional-managerial-consultant ideology, it is vital that academics across institutions globally work to strengthen faculty governance and oversight over decision-making processes, attending closely to the threats to academic freedom externally and internally, anticipating them, and responding to them pro-actively. In the US, elected bodies such as faculty senates carry out this powerful role of holding university managers accountable.

It is also critical that academics work alongside university leadership in developing institutional pedagogies around the threats posed by the far-right, mapping the pathways and sites of attacks, and developing and institutionalising strategies for responding.

For instance, one of the core strategies of the far-right is to pose as aggrieved students and concerned community members to carry out attacks targeting academics, often operating through fake social media accounts, anonymous email addresses, fake websites, sock puppet accounts, automated bots, troll farms, and instant messaging apps such as Telegram and WhatsApp. Email campaigns and university complaint portals are co-opted as tools for carrying out such swarm attacks, with influencers manufacturing grievance to mobilise such campaigns and directing followers to lodge complaints, working alongside automated bots and troll farms.

Educating staff in front-facing roles in sifting through and identifying spurious complaints, in detecting far-right disinformation-based narratives in the complaints, in raising the appropriate security alarms, and adequately responding to these narratives, is critical. Similarly, given the deployment of Official Information Act (OIA) requests to feed far-right propaganda, responding proactively to the propaganda and debunking it is critical. Also crucial is building the capacity of university managers in detecting potential instances of foreign interference and raising these through appropriate channels within the university. Such pedagogy needs to be built preventively across institutions, given the message swarms that far-right campaigns build, often funded by powerful political and economic interests, including right-wing think tanks, lobbies, astroturfs, and foundations.

Moreover, relevant state structures and institutional processes ought to be able to support universities with addressing the concerns raised, given the threats to institutional processes and democracy, and critically in the context of foreign interference into academic freedom through organised campaigns.

Building legal infrastructures

In the case presented above, Texas A&M reached a $1 million settlement with Professor Kathleen McElroy. The report released by the University General Counsel demonstrated egregious process violations. During the hiring process, university officials initially pushed for a delay until after the state legislative session adjourned, anticipating potential backlash from conservative lawmakers. Following complaints about her hiring raised by university regents, officials changed the terms of her contract.

As the process unfolded, with the terms of her contract changing significantly, Professor McElroy responded to the university, asking it to communicate through her lawyers.

In a similar high-profile case, Black journalist, Pulitzer-prize-winning author for the New York Times, and founder of the New York Time’s 1619 Project, a long-form journalism endeavour that documents the intertwined histories of slavery and the founding of the United States and was earlier labelled by Trump as “ideological poison,” Nikole Hannah-Jones, was initially offered a tenure track position by the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, that was then changed to a five-year contract.

Documenting the far-right backlash against her Pulitzer Prize-winning 1619 Project and targeting of critical race theory education, Hannah-Jones noted:

“Journalism schools reflect the same reality we see in the rest of the country…Why it’s especially troubling in journalism is that journalism is the firewall of our democracy. Journalism is what’s supposed to be exposing the way power is wielded. If that story is being filtered through an almost exclusively White lens, it’s not accurate. It’s not capable of helping us… understand the country we live in.”

She was supported by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) Legal Defense and Educational Fund in seeking justice through the legal framework. The university reportedly reached a settlement on the tenure dispute for less than $75,000.

The Hannah-Jones settlement is instructive because it includes several structural changes, proving the “correctness of critical race theory.” It outlines an inclusive search process for new employees in conjunction with the Office of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion; mental health counselling placed within the Multicultural Health Programme, complemented by the hiring of an additional trauma-informed therapist; and a $5,000 annual funding to the Provost’s Office to coordinate meetings and events sponsored by the Carolina Black Caucus working alongside UNC-Chapel Hill Vice Provost.

The far-right often directs its attacks on academics identifying with diverse marginalised positions. For instance, as with the examples of the organised campaigns targeting Professor McElroy and Hannah-Jones, the far-right interferences into university processes are racist, violating the fundamental human rights of academics having a protected characteristic. Building legal infrastructures such as the NAACP is critical to resisting the interference of the far-right into university processes.

Seeing and materialising connections

The organising structure of far-right hate produces its effect through the creation and amplification of fear. The mobilisation of fear results in swarms that target and attack academics and universities. These swarm-based campaigns have chilling effects, threatening the livelihoods and lives of academics.

The effects of these campaigns are amplified by the individualising processes that often place the onus of securing safety on individual actions to be taken by those being targeted. Consider the targeting of the University of Auckland academics, Associate Professor Siouxsie Wiles and Professor Shaun Hendy. The pair became the targets of attacks directed at their work explaining the science behind COVID-19. In a complaint to the Employment Relations Authority (ERA), they noted the university had failed its duty of care to them.

Attacks such as these call for the allocation of institutional resources to support academic freedom for public scholarship.

However, amidst the ongoing cuts to university funding globally including here in Aotearoa, finding the resources and allocating them to security (including digital security), legal support, mental health support, and media support is a challenge for leaders. Making provisions for security on funding applications and allocating funding resources for security to universities are two policy responses that can offer meaningful safeguards. The inclusion of community and social impact in the Performance-Based Research Fund (PBRF) ought to be combined with funding allocated to building safeguards around public-facing impactful scholarship. To advocate for such policy-based support, it is important that academics, unions, students, university leaders and policymakers work together.

Academic solidarities globally have been crucial to challenging the attacks by far-right campaigns. Letter writing campaigns and petitions have been vital in both responding to and developing preventive infrastructures for addressing the threats posed by far-right campaigns targeting individual academics, programmes of research, and academic departments.

Academic organising across institutions is a critical resource in mapping and responding to the interplays between institutional racism and far-right attacks. Disciplinary associations here can play central roles in responding to the organised attacks, developing both preventive measures as well as effective responses. Responding to the far-right attacks on communication education and scholarship, my disciplinary association, the National Communication Association (NCA), issued the following statement:

“As the preeminent scholarly society devoted to the study and teaching of Communication, NCA recognizes that professional educators, including Communication scholars and teachers, are best equipped to determine what is appropriate for their classrooms and curricula. Among other theories that plainly acknowledge the histories and impacts of race, Critical race theory (CRT) is foundational to effective communication teaching, learning, and practice. Simply stated: Educators cannot effectively teach communication without teaching about systemic racism and its impact on our institutions and policies, including teaching about CRT and its principles. Students cannot adequately learn about effective communication without exploring systemic racism in the history of the United States. To restrict freedoms to engage in the teaching of, and communication about, CRT and other theories which examine the historical and current impact of their principles is inconsistent with the principles of democracy. NCA opposes legislation that would censor content within the curriculum or classroom based on political disagreement or contrived controversy, particularly when such legislation curtails or prohibits teaching about the role of racism, sexism, and other forms of discrimination in the United States historically and today.”

The American Association of University Professors (AAUP) is an example of an organisational structure that is critical to safeguarding academic freedom in the US. Tracking the far-right campaign attacking Critical Race Theory in the form of bills passed across various states to Trump and the Make America Great Again (MAGA) campaign, noted the AAUP in its report:

“Language in these bills draws from Trump’s 2020 executive order on Combating Race and Sex Stereotypes and can be found in model legislation being pushed by MAGA lobbying arm Citizens for Renewing America. Both the executive order and model legislation are influenced by Russ Vought, Trump’s former budget director, who founded CRA. CRA is funded by the Conservative Partnership Institute, which is an effort by Trump allies to formalize extremist, far-right politics in the think tank sphere. Other organizations included under the CPI umbrella are the American Accountability Foundation, which attacks President Joe Biden’s Cabinet and judicial appointees, and America First Legal, which is run by former Trump speechwriter Stephen Miller and focuses on litigation that “oppose[s] the radical left’s anti-jobs, anti-freedom, anti-faith, anti-borders, anti-police, and anti-American crusade.” According to 2021 tax filings, CPI had an annual budget of $17.1 million, and revenues of $45.7 million.”

In the instance of the process lapses and racist institutional biases in the hiring of Hannah-Jones, the AAUP noted in the report titled, Governance, Academic Freedom, and Institutional Racism in the University of North Carolina System:

“In the case of retention of faculty members and administrative officers of color, while the individual motivations for their departures may be unclear, what is clear is that in one way or another a culture of exclusion, a lack of transparency and inclusion in decision-making, the chilling of academic freedom, discounting certain kinds of scholarship and teaching, and the constant threat of political interference have combined to fuel what some have called an “exodus” from the UNC system.”

Across global registers, it is critical to consider the possibilities for building academic associations committed to safeguarding scholarship. In Aotearoa for instance, such an organisation would among addressing other elements critical to academic freedom, track the funding flows of far-right hate and map potential foreign interference both discursively and materially, assess the risks to academia posed by disinformation campaigns, and respond robustly. Building partnerships with university leadership and relevant ministries are equally important in delineating the foreign interference at work (such as in the example of the “culture war” hysteria) and in developing preventive strategies to respond to it. Mobilising unions to address the threats to academic freedom is another potential avenue.

In addition, building solidarities with communities, civil society, and social movements is vital to resisting the forces of the far-right. The recognition that the attacks on universities are part of a broader pattern of attacks mobilised by the far-right ought to serve as the basis for crafting solidarities that witness and challenge the pernicious narratives and hate campaigns at societal levels. Connecting with activists and lending solidarity to those who are targeted by the far-right are critical to creating the broader infrastructure for resistance.

In the attacks I have experienced recently mobilised by the racist disinformation campaign launched by far-right networks here in Aotearoa, I have been humbled to be supported by collectives of activists, anchored in Māori leadership. When I discussed these targeted attacks with activists Tina Ngata and Sina Brown-Davis, they wrapped me up in a collective network of care. Within a few hours of our conversation, I had an email from The Manaaki Collective, offering a blanket of support, from security to legal assistance.

Te Tiriti and global leadership

The principles of Te Tiriti, foregrounding the values of participation, protection, and partnership offer powerful registers for resistance to white supremacy.

In Aotearoa, Māori have historically challenged racism and white supremacy in transformative ways, dismantling the hate politics of settler colonialism with the values of manaakitanga (caring about each other’s wellbeing, nurturing relationships, and engaging with one another) and whanaungatanga (forming, maintaining, and nurturing relationships and strengthening ties between kin and communities). Māori struggles for Te Tiriti justice have historically offered inspiration and hope to diverse struggles for social justice in Aotearoa and globally.

The Māori activists who have participated in the Activist-in-Residence programme at the Centre for Culture-Centered Approach to Research and Evaluation (CARE), Tame Iti, Teanau Tuiono, Dr Ihirangi Heke, Marise Lant, and Tina Ngata each outline the transformative power of connection as the organising basis for approaching relationships among human beings, in and between communities, and with land and the ecosystem. This meta-theory of “connection as organising” lies at the frontiers for pushing back against white supremacist hate.

The sustained resistance to white supremacy offered by Māori activists and communities position Aotearoa as a leader for global progressive struggles against white supremacy, and for interconnected struggles for climate justice, racial justice, Indigenous rights and migrant rights. Amidst the disenfranchising effects of white supremacy that seek to silence activist and academic voices, the inspiring work of The Manaaki Collective offers a global model for Indigenous leadership in securing safe spaces for organising “for racial, social, environmental, and Te Tiriti justice.”

As a university aspiring to be Te Tiriti-led, Te Kunenga ki Pūrehuroa Massey University has articulated the commitment to sustaining “a reputation for caring, inclusion and equity, and commitment to our people, our environment, and our places,” a commitment that speaks directly to the principles of Te Tiriti. I am proud of our university which puts forth a justice-based framework for academic freedom, in dialogue with the commitments of Te Tiriti, leading globally with a model that can sustain universities in safeguarding against disinformation campaigns by the far-right.

In conclusion

I wrap up this opinion piece by directly addressing the propaganda infrastructures of the far-right. Our message to the far-right reactionaries, in politics, in the media, on digital platforms, and in various hate formations, is loud and clear.

Backed by powerful economic forces, often hiding behind astroturfs, sock puppets, instant messaging apps, automated bots and fake websites, the far-right have launched propaganda campaigns that deliberately distort scholarship to suit the white supremacist agenda, confident that the targeted attacks can ban the teaching of critical concepts of social justice, and thus erase the powerful waves of voices emergent from the margins mobilising for transformational change.

And in spite of the economic power and political influence, replete with a digital infrastructure fuelling the dissemination of disinformation and hate, exponentially magnified by the globally linked hate networks, the far-right will continue to fail in securing hegemony.

The hate and divisive narratives that seed and propagate fear will fail because, as articulated forcefully by Martin Luther King, Jr, “the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice.”

The far-right threats to stalk us, get us fired, get us and our families deported, incarcerate us, rape us, dox our families on social hate platforms, and kill us will not silence the conviction of our scholarship, and the public impact this scholarship creates. We will continue to, along with the communities we partner with, carry out our research, generate empirical evidence that empowers communities in their struggles for justice, and transform the status quo.

Our public scholarship will continue to build registers for hope. Communities at the margins will continue to rise up, raise their voices and challenge the marginalising processes that seek to silence them.

In not cowering to the fear-based campaigns of the far-right, we will continue to be inspired by the words of Indigenous activists. In the words of activist Sina Brown-Davis, “Be unafraid, be powerful, we have everything to fight for and nothing to lose.”

Link to Massey News page: https://www.massey.ac.nz/about/news/opinion-this-is-how-we-fight-back-the-academes-resistance-to-the-far-rights-culture-war/

Professor Mohan Dutta is Dean’s Chair Professor of Communication. He is the Director of the Center for Culture-Centered Approach to Research and Evaluation (CARE), developing culturally-centered, community-based projects of social change, advocacy, and activism that articulate health as a human right. He is a member of the board of the International Communication Association.