2025 Oceania Hub ICA Conference 13-16 June 2025

Check out the 2025 Oceania Hub ICA Conference Programme

Massey to host Oceania hub of the International Communication Association conference

CARE is hosting our next dialogue

“Breaking the Silences: India Pakistan Conflict.”

Dr. Fatima Junaid, Massey Business School, will bring her research on violent extremism and trauma in conversation with CARE Director Professor Mohan Dutta.

Friday, May 16, 2025

8 p.m.

On CARE YouTube Channel: CARE Massey – YouTube

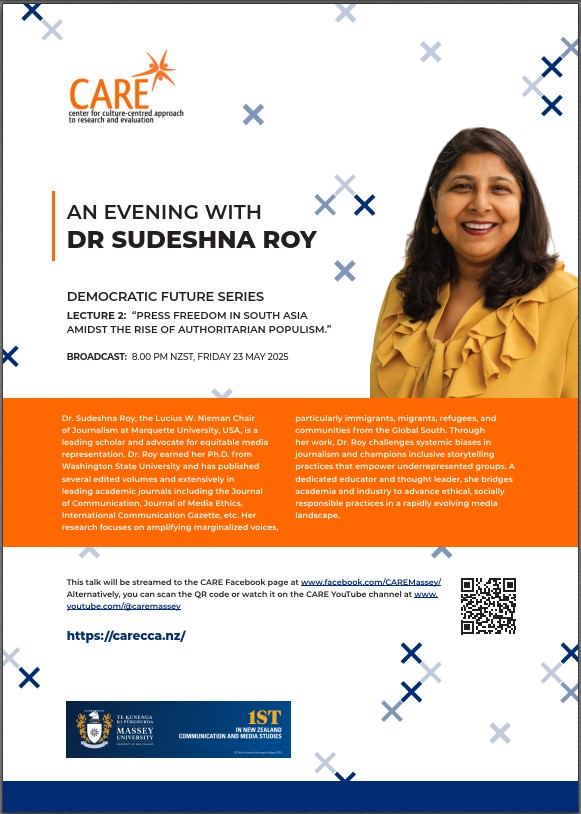

Democratic Future Series – Lecture 2

“Press Freedom in South Asia amidst the rise of Authoritarian Populism”

Note change of time to – Friday 23 May 2025 8pmm NZST, Dr Sudeshna Roy

Lecture 2 hosted by Dr Sudeshna Roy followed by a Q & A with Professor Mohan Dutta next Friday 23 May 2025 8pm NZST. Live streamed on Facebook or alternatively you will be able to view it on CARE’s YouTube channel.

https://www.facebook.com/CAREMassey

https://www.youtube.com/@caremassey

#CAREMassey #CARECCA #MasseyUni #MasseyUniNZ #democracy #Populism #PressFreedom #SouthAsia

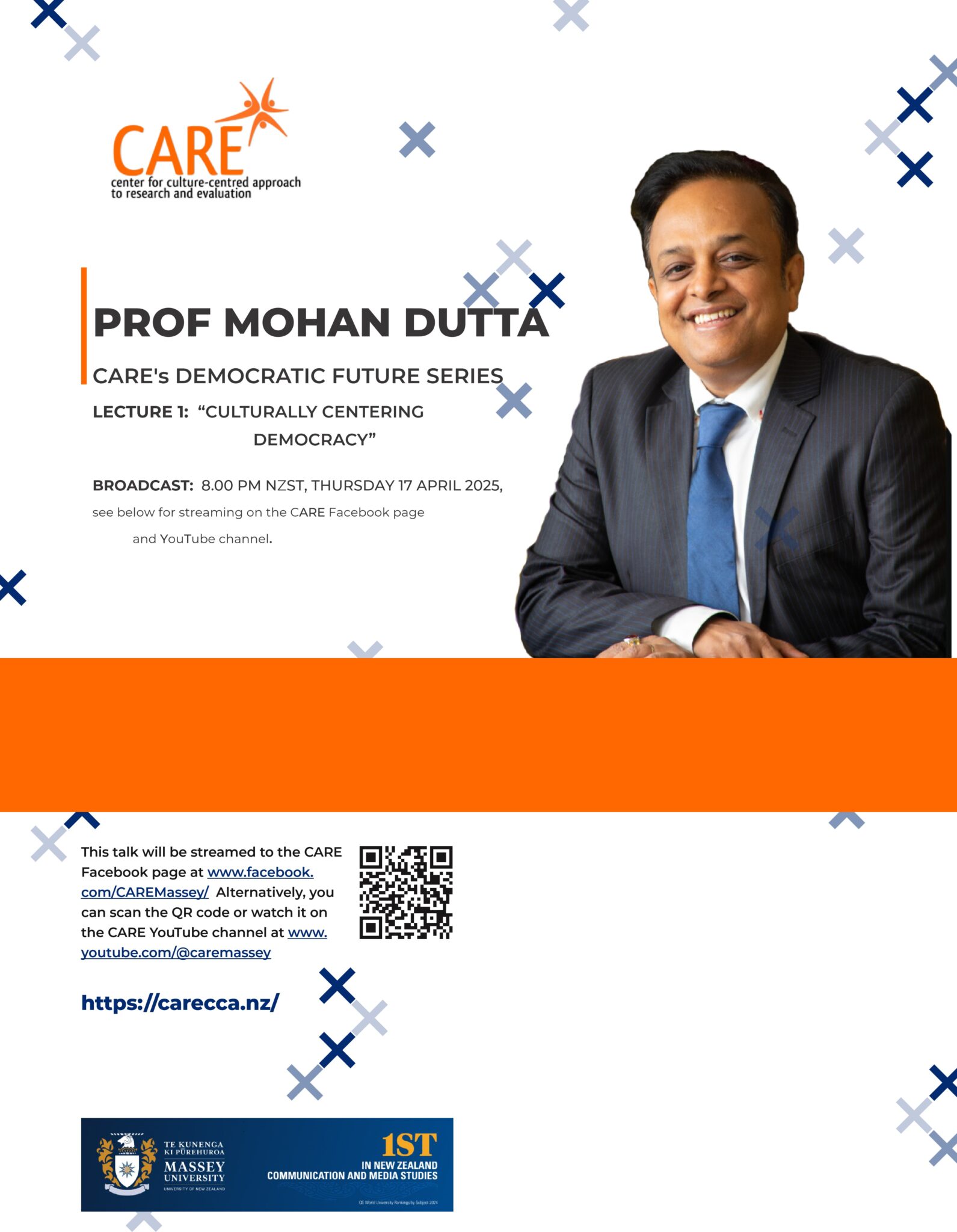

Democratic Future Series – Lecture 1

“Culturally Centering Democracy”

Thursday 17 April 2025 8pm NZST, Professor Mohan Dutta

Coming soon CARE’s Democratic Future Series – Lecture 1 hosted by Professor Mohan Dutta “Culturally Centering Democracy” this Thursday 17 April 2025 8pm NZST. Live streamed on Facebook or alternatively you will be able to view it on CARE’s YouTube channel.

https://www.facebook.com/CAREMassey

https://www.youtube.com/@caremassey

The Free Speech Union’s targeting of Universities: Why we must resist the distortions

Monday 17 March 2025, By Professor Mohan Dutta

Universities have increasingly found themselves as targets of Far-Right campaigns seeking to destabilize them. In Aotearoa as in connected settler colonial spaces, this Far-Right campaign is the face of white supremacy, seeking to platform extremists, and concocting a discourse of panic around the Western University in danger because of the struggles put forth by Indigenous, Black, ethnic migrant and diverse intersectional communities against the prevailing ideology of white supremacy.

At the core of the moral panic propagated by the Far-Right is the construction of the University as a hallowed institution of Western civilization (as if Universities and knowledge generating spaces didn’t exist outside of the West). Projecting Indigenous, Black, and migrant communities as threats to Western values, the racist campaign of the Far Right seeks to return the modern University to its good old days. Consider the following post by McGimpsey, a Case, Research and Drafting Advisor at the FSU until March, 2024.

These good old days reflect the times before critical race theory; diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI); and decolonization. In Aotearoa, these good old days are concocted fabrications of a past pre Te Tiriti.

These good old days are days of yore before the colored multitude took over the Universities and turned them into woke bastions!

Positioning itself as the advocate of free speech in Aotearoa and uncritically deployed by the media as a credible source on free speech issues (in spite of multiple analyses that have debunked the methods deployed by the FSU), the Free Speech Union draws on this narrative of decolonization and DEI as threats to the Western ideals of academic freedom.

It glorifies a false narrative of the Anglosphere as the strongest anchor for peace and prosperity, actively erasing the empirically documented history of colonial violence. Consider the following post from the FSU’s X handle, which the handle later apologized for after being publicly called out for the racism.

The FSU is very much a part of the broader global infrastructure of propaganda seeking to impose a narrow definition of free speech and academic freedom on Universities, strategically conflating the two, driven by the agenda of upholding and reproducing the hegemonic status quo.

This broader context offers explanatory ground for understanding the systemic attack launched by FSU on Massey University. The University and its progressive vision that aspires to build a future shaped by Te Tiriti offers a decolonising register that fundamentally threatens the ideology of white supremacy. An earlier decision by the University to not host an event with Don Brash because of the leadership’s worry around being seen as endorsing racism placed it as a target of the FSU.

It is no surprise then that the PULSE survey on organizational climate at Massey University secured through an OIA request becomes the lightning rod for FSU to amplify its campaign targeting the University. The FSU framing of the survey is constructed around ideas of academic freedom. An FSU letter and an RNZ story quoting the FSU state, “Universities rely on voices being free. How do academics progress knowledge in an environment that doesn’t welcome debate and dissenting ideas?”

The FSU hyperbole would lead the reader to believe academic freedom is under threat at Massey. Yet, critical interrogation of the claim lays visible its vacuous form. The hyperbole from FSU is in response to a qualitative comment on the section on Two-way communication, which stated, “Staff also fear that they are not safe to express their honest opinions for fear of reprisal of being seen as not towing the party line.” That cherry picked sentence (We know from my past analyses that the FSU has a penchant for cherry picking responses to fit its ideological agenda) is part of a broader excerpt in a section on staff responses to the prompt, “At Massey University there is open and honest two-way communication.” The prompt had nothing to do with progressing knowledge within one’s own expertise area and the freedom to do so.

The broader paragraph that showcased the example read:

“Staff feel there is a lack of open and honest two-way communication at Massey University. They perceive that senior leadership is not transparent and that important decisions are made without sufficient consultation or input from staff and students. Staff also feel that they are not safe to express their honest opinions for fear of reprisal or being seen as not towing the party line.” The paragraph in its entirety seems to be speaking to the decision-making and consultation processes in the management and administration of the University. It is clear that the staff perceptions of two-way communication are around the University’s day-to-day management functions, not around academic freedom in topic areas of expertise.

The same section also has positive and neutral examples of staff response. The positive response for instance states:

“Staff feel confident that their PVC and HoS are receptive to feedback and make changes when needed. Staff also appreciate the collegial and friendly atmosphere at Massey and feel fortunate to have supportive supervisors who they can communicate with freely. The official and legally correct communication style of the university is also seen as a positive.”

The neutral response states, “There is open and honest two-way communication among staff within schools and between colleagues. However, there is a lack of transparency in leadership decision-making and communication from senior leadership to staff. Some staff feel that their concerns are not listened to and that there is a level of distrust among staff about messages coming from senior leadership.”

Again, both of these responses are reflective of what the overarching prompt was about, perceptions about two-way communication in the organizational practices of the University. Unlike what the FSU makes the responses to look like, the qualitative comments across the spectrum reflect the objective of the prompt, to gauge staff perceptions about two-way communication in the management of the University.

When one picks qualitative comments for analyses, there are going to be a wide range of responses that capture diverse opinions. Considering the sentiment analysis of the generated narratives in response to the prompt, it is worth noting that 5% of staff offer positive responses, 29% offer neutral responses, and 66% offer negative responses. What this does point to is the opportunity to grow two-way communication across the layers of decision-making in the University. The sharing of the PULSE survey report itself, including the range of responses is an exemplar of transparency, a critical step toward building two-way communication. Moreover, the survey itself is part of a process that can work toward building and growing organizational culture.

One might ask, how would I personally respond to the item? I have access to this survey and to diverse platforms to communicate my views on this issue of organizational communication and will certainly not be turning to the FSU to communicate my perception.

What the prompt and the responses to it however don’t capture is academic freedom. There is no evidence to support FSU’s mischievous framing “How do academics progress knowledge in an environment that doesn’t welcome debate and dissenting ideas?” The prompt that generated the responses had nothing to do with academic freedom. Broadly, the PULSE survey actually is not designed to evaluate the space for dissenting (academic) ideas. It is not an academic freedom survey. In fact, when you look at the entirety of the PULSE survey, you recognize that the survey is not designed to evaluate the climate of the University around academic freedom, the freedom to teach and research ideas in one’s area of expertise. That would be an important survey to have on hand, but this isn’t it.

Why then does the FSU construct this slippage between organizational climate and academic freedom? It is my sense that this slippage from staff response to questions of organizational communication and processes to academic freedom is part of a broader ideological agenda of the FSU around creating a moral panic around academic freedom, decolonization and Te Tiriti.

As I have noted in the past, when it comes to academic freedom, when my academic freedom has been targeted, initially by Hindutva extremists, the FSU was absent. Not only did it not have any public statements to make around the organized campaign targeting my academic freedom, it also went ahead to platform one of the Hindutva propagandists who also appeared on Counterspin, and had organized a campaign targeting my job at the University. I will also note here that when I had publicly noted this strategic absence of the FSU, one of its propagandists had suggested I was lying although they couldn’t offer any evidence of FSU offering support for my academic freedom.

More recently, in the context of my critiques of Zionist settler colonialism and the ongoing genocide being perpetrated by Israel in Gaza, far-right Zionist infrastructures in Aotearoa have targeted my academic freedom based on planted misinformation. This campaign is part of a broader campaign in Aotearoa launched by Far-Right Zionists targeting academic voices critical of Israel. Two of these Zionist creators and disseminators of disinformation sit on or have sat on the Board of the FSU (The exhibit below shows one of the posts by David Cumin, based on misinformation about the claim I made and that I have deleted a blog post, which I never did. See here). One of these Zionist propagandists targeted my job at Massey University, tagging the University and sought to get me fired.

In the face of public criticism that noted the hypocrisy of the FSU, the propagandist then peddled the same misinformation in an email sent out from the FSU email address to the FSU listserv. This resulted in increased hate and trolling that I received, including hate messages left on my official email and phone threatening to send me back to ‘wherever I came from.” Now these are actual examples of threats to academic freedom, and they originate from within the infrastructures of the FSU.

I will wrap up by making a critical observation, that in the face of the threats to my academic freedom, including in instances of foreign interference, my employer, Massey University Te Kunenga ki Purehuroha, has stood firm and stood tall by me. This public support by the University and its senior leaders has meant that the University has become a source of further aggravated attacks from the Far-Right on its institutional structure and processes. It has offered the necessary critical support, the support with security, and the support with care, including Senior Leadership calling up on me to check how I am doing. In the face of the threats to my academic freedom that came directly from the networks of the FSU, the fear that this campaign induced in me around my safety and public scholarship, my employer has stood by me. I would any day take the commitments and negotiations of the University I work in around questions of academic freedom seriously than I would an astroturf organization seeking to insert a wedge around academic freedom to serve its ideological agenda of dismantling the critical decolonization work much needed in our Universities in Aotearoa and globally.

The work of decolonization must go on.

Disrupting and Consolidating Communication Research: Applying Communication Theory to Practice

June 12-June 16, 2025

Massey University, Palmerston North, Aotearoa New Zealand

Oceania Hub: Aotearoa New Zealand

Hosted by:

Center for Culture-Centered Approach to Research and Evaluation (CARE)

Communication and Media Studies at Massey University

Organizers: Debalina Dutta, Sy Taffel, Sean Phelan, & Mohan Dutta

Call for Submissions Due Date: March 7, 2025, 11:59 pm NZST

The Oceania Hub of the International Communication Association (ICA) 2025 conference, hosted at Te Kunenga ki Pūrehuroa Massey University in Aotearoa New Zealand, explores questions surrounding disrupting Communication Research through the lens of Te Tiriti and Social Justice. Drawing on communication scholarship organized around the various registers of social justice, the Hub examines the intersections of communication theorizing and practice, mobilized toward disruptions and consolidation. The hub will be held in hybrid form, with both in-person and virtual sessions. Selected panels, papers, and interventions will be considered for waiver of conference registration fees.

We invite disciplinary and interdisciplinary submissions and multimedia communication interventions (video stories, film, performances, art forms, photographic images, sound productions) from the broader Asia-Pacific, focusing on the representation of the scholarship of communication practice from the Islands of the Pacific. The salience of Pacific participation is constituted around the global sustainability challenges of climate change, rising water levels, extreme inequality etc. We see the hub as offering an opening for disrupting what counts as communication scholarship through the engagement with practices of communication for social change.

The ICA Regional Hub at CARE will comprise a one-day hybrid workshop on “Connecting theory and practice as disruptions.” The workshop will bring in scholars from across the Asia-Pacific in both virtual and face-to-face sessions, focusing on key questions exploring the intersections of theory and practice in the context of addressing complex global challenges at a time when reactionary forces are on the rise. Aligned with the ICA 2025 conference theme of “Disrupting and Consolidating Communication Research,” the workshop will center the questions of disruptions from the context of the Pacific, anchoring the conversations in the struggles for justice and/or sustainability among others in communities across the Pacific. Sessions will connect with local organizers and activists in generating conversations on key questions on decolonizing knowledge. Centering the principles of Kaupapa Māori and indigenous methods across Asia and the Pacific, the workshop will explore the role of community as an organizing space for building knowledge.

The Hub will operate in a hybrid model, with face-to-face participation complementing virtual participation. We welcome paper or panel submissions on the following topics and beyond:

- The futures of struggles around diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI)

- Theorizing communication applications

- Decolonizing communication scholarship

- Sustainable communicative futures

- Science communication futures

- ‘Disruptive innovation’ and social justice

- AI and/as disruption

- Disruptive alternatives to corporate platforms and infrastructures

- Indigenous data sovereignty

- Internationalization of the culture wars

- Communication theory and mutant neoliberalism

- The normalization of reactionary politics

- Cultures of political resistance

- Health communication and social determinants

- Climate justice

- Communication theory, transdisciplinarity and interdisciplinarity

- Media cultures and ecologies

- Imperialism, geopolitics and multipolarity

- Critical development communication

We extend a special invitation to postgraduate students, activists and scholars from the Global South, Indigenous, LGBTQIA+ and those living with disabilities.

We invite submissions from the region addressing the theme “Disrupting and consolidating Communication Research.” The submissions can take the form of academic papers as well as multimedia forms beyond the text such as photos, audio, video stories, film, performance etc.

Please submit a title and an abstract no longer than 250 words. If you are submitting a multimedia intervention, please describe the interventions in the abstract. Please email your submission to Debalina Dutta at D.Dutta@massey.ac.nz by March 7, 2025, 11:59 pm NZST.

Professor Mohan Dutta receives 2024 Global Communication Award

Professor Dutta has been recognised for his pioneering work in de-westernising communication research and promoting social justice through community-led initiatives.

Professor Mohan Dutta, Dean’s Chair Professor of Communication and Director of the Center for Culture-Centered Approach to Research and Evaluation (CARE) at Te Kunenga ki Pūrehuroa Massey University has been named as the winner of the 2024 Global Communication Award from the National Communication Association (NCA).

The Global Communication Award recognises distinguished communication scholarship that de-westernises ways of knowing and doing, focuses on regions, communities, or spaces outside of the United States (US) and Europe, integrates and cites international and global scholars, theories, approaches and/or methodologies in their scholarship and amplifies the global ecologies of knowledges.

Through his scholarship spanning three decades, Professor Dutta has created new openings for communication research and theory of/from the Global South, decentring the North Atlantic dominance of communication studies. He developed the culture-centred approach as a communication theory for conceptualising the ways in which communities of the Global South have been historically marginalised by the intertwined processes of colonialism, racial capitalism and imperialism.

His research programme, created in partnership with communities struggling against these marginalising forces, seeks to build voice infrastructures for community participation and decision-making in struggles for just futures. The academic-community partnerships he has created and sustained across the globe foster spaces for mobilising for social change.

From partnering with Adivasi (Indigenous) communities in Eastern India to build Indigenous-led community education programmes and cultural resources, to partnering with youth in the US Midwest to co-design an anti-tobacco advertising campaign and partnering with communities in Highbury and Feilding in Aotearoa New Zealand in co-creating community-owned food systems, violence prevention programmes and communication advocacy campaigns, the impulse of Professor Dutta’s work is rooted in securing justice.

The award citation states, “Dr Dutta evinces a deep commitment to social justice as a transnational project and has assiduously worked to forge ethical ties across different geopolitical terrains. Thus, Dr Dutta’s work continues to inspire scholars from marginalised communities, exemplifying the qualities of this award.”

Spanning 17 countries and four continents, the scope of Professor Dutta’s research and leadership, evidenced in his directorship of CARE, fosters the communication capacities of communities experiencing systemic disenfranchisement. Across local, national, regional and global spaces, the work of CARE builds sustainable linkages and connections among struggles for justice. The impact of Professor Dutta’s scholarship is evident in the power of community-led advocacy in influencing policies addressing social injustices. The community-led research collaborations he has built have shaped a wide array of community development projects, including community-owned food systems, hospitals, Indigenous cultural resources, educational infrastructures, systems for clean drinking water and community- and worker-owned advocacy and activist campaigns.

Professor Dutta says the award is a recognition of the global impact of the world-class research being carried out at CARE.

“It’s a collective of researchers, community organisers, advocates, activists and civil society organisations that actually carry out the work in community. The steadfast support of Massey University fuels our research programme.”

Since its relocation to New Zealand in 2018, CARE has carried out over 50 community-led social change projects addressing the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) around no poverty, good health and wellbeing, reduced inequalities, climate action, zero hunger, clean water and sanitation, sustainable cities and communities, peace, justice and strong institutions and partnerships for the goals.

The most recent scholarship of CARE, on challenging Islamophobia, builds partnerships with communities and civil society organisations in mapping online and offline Islamophobia, developing community-led culture-centred digital literacy programmes challenging Islamophobia and strengthening community capacities in securing peace. White papers and policy briefs derived from the research have played critical roles in shaping public policies around social cohesion and anti-racism.

The activist-in-residence programme, white papers and community and public dialogues offer templates for community-engaged scholarship with global reach. In addition, CARE regularly hosts international researchers, community organisers, civil society organisations and students from across the globe who are interested in learning about the culture-centred approach to social change. So far, it has trained over 100 researchers, community organisers and peer leaders on the principles and methods of the culture-centred approach. A documentary featuring the work of CARE is available here.

The international reach of Professor Dutta’s mentorship has been recognised with the Aubrey Fisher Mentorship Award and the NCA Health Communication Division’s award for outstanding contributions to promoting equity and inclusion. He also received the NCA Presidential citation for his contributions to de-centring the whiteness of the discipline through his public scholarship and activism.

Professor Dutta’s scholarship has also been recognised with the prestigious Charles H. Woolbert Research Award, the NCA’s Golden Anniversary Monograph Award, Applied Communication Award, the Bridge Award for Excellence in Connecting Crisis and Risk Communication Research and the International Communication Association’s Applied Public Policy Communication Researcher Award.

He is a Distinguished Scholar of the NCA and Fellow of the ICA.

About the National Communication Association (NCA)

The NCA advances communication as the discipline that studies all forms, modes, media and consequences of communication through humanistic, social scientific and aesthetic inquiry. The NCA serves the scholars, teachers and practitioners who are its members by enabling and supporting their professional interests in research and teaching.

Dedicated to fostering and promoting free and ethical communication, the NCA promotes the widespread appreciation of the importance of communication in public and private life, the application of competent communication to improve the quality of human life and relationships and the use of knowledge about communication to solve human problems. The NCA supports inclusiveness and diversity among their faculties, within their membership, in the workplace and in the classroom, and supports and promotes policies that fairly encourage this diversity and inclusion.

NCA’s annual awards will be bestowed on several distinguished members at the NCA 110th Annual Convention in New Orleans, Louisiana. Below is the list of those who will be honored at the awards presentation.

#ProfessorMohanDutta #GlobalCommunicationAward #NCA #CAREMassey #MasseyUniversity #CARECCA #CommunicationScholarship #DeWesternization #GlobalSouth #SocialJustice #CommunityEngagement #CARE #MasseyUniversity #CulturalCenteredApproach #VoiceInfrastructures #CommunityPartnerships #SocialChange #UNSDGs #Islamophobia #PublicScholarship #EquityAndInclusion #AcademicFreedom #CommunicationResearch #GlobalImpact

Source: Massey News- Professor Mohan Dutta receives 2024 Global Communication Award – Massey University & NCA

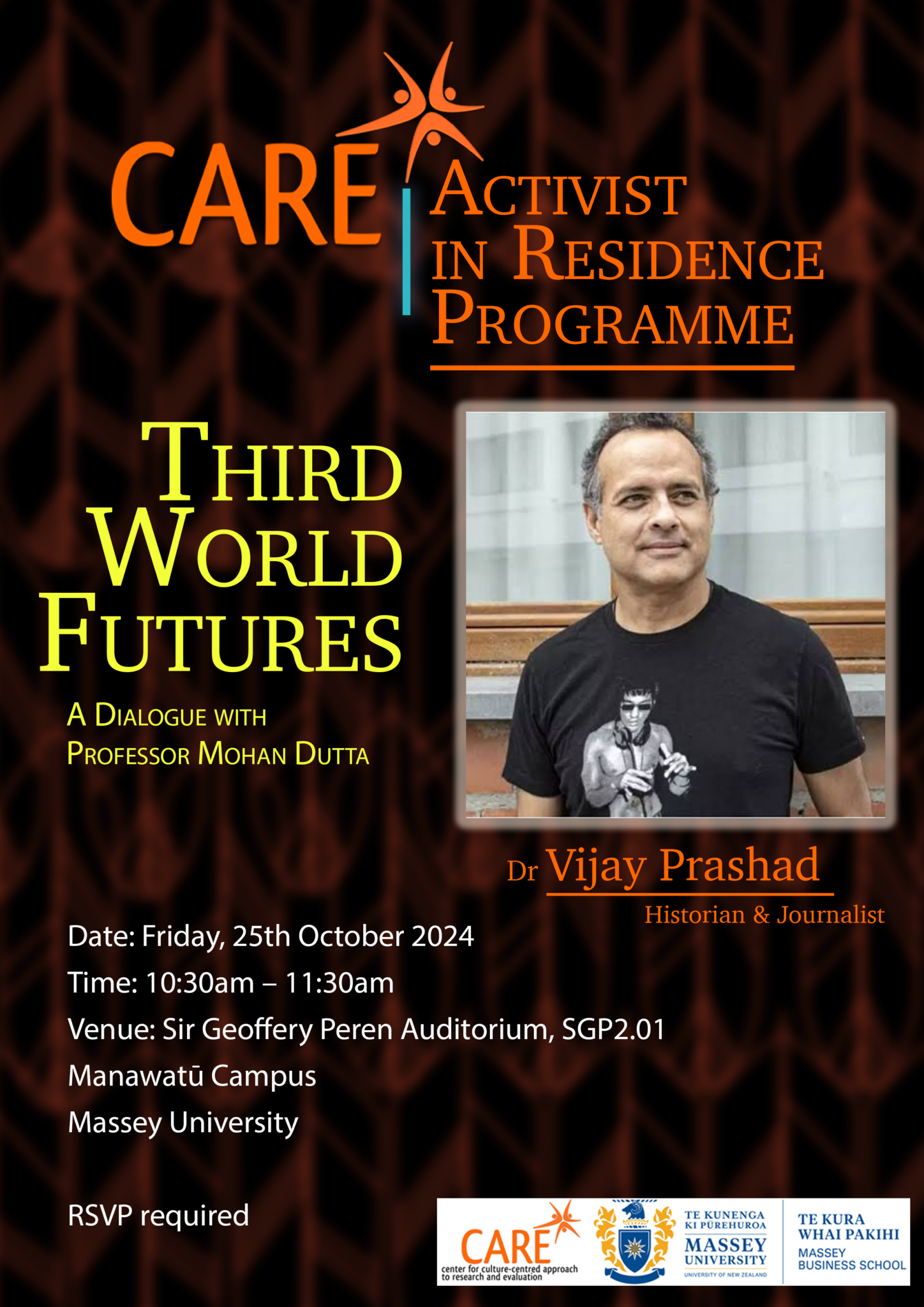

CARE Activist in Residence Programme Dr. Vijay Prashad | 25 October 2024

Center for Culture-Centered Approach to Research & Evaluation (CARE), Massey University is excited to announce the Activist in Residence Programme featuring a world-renowned historian and journalist Dr. Vijay Prashad.

This highly anticipated CARE event called Third World Futures – A Dialogue with Vijay Prashad and Professor Mohan Dutta will take place on 25th October 2024 at the Sir Geoffrey Peren Auditorium (SGP2.01) on the Manawatū Campus, Massey University at 10.30 am NZDT.

About Dr. Vijay Prashad

Dr. Vijay Prashad is a distinguished Indian historian, journalist, and author, widely recognized for his influential work on global history and politics. He has authored forty books, including prominent titles such as Washington Bullets, Red Star Over the Third World, The Darker Nations: A People’s History of the Third World, and The Withdrawal: Iraq, Libya, Afghanistan, and the Fragility of U.S. Power, co-written with Noam Chomsky.

In addition to his literary contributions, Dr. Prashad serves as the executive director of Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research, the chief correspondent for Globetrotter, and the chief editor of LeftWord Books in New Delhi. He has also appeared in the films Shadow World (2016) and Two Meetings (2017), which further amplify his critique of global power dynamics.

The CARE Activist in Residence Programme offers a unique opportunity to engage with Dr. Prashad’s extensive research and activism, spanning topics from the history of the Global South to the fragility of U.S. power in the 21st century. Attendees will gain insights into current global political challenges and the transformative role of activism and scholarship.

This event is free to attend and open to all. We look forward to welcoming you to what promises to be an enlightening and inspiring discussion.

Watch the full event recorded on the CARE YouTube and CARE Facebook channels:

YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1sLGQtHdFF8

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/events/1399316128140020

Facebook events page: https://www.facebook.com/events/1237882210738575

RSVP here: https://forms.office.com/r/GVXSdq2Sh1

Event Details:

– Date: Friday, 25th October 2024

– Time: 10:30 AM – 11:30 AM NZDT

– Venue: Sir Geoffrey Peren Auditorium (SGP2.01), Manawatū Campus, Massey University (Google Maps: https://maps.app.goo.gl/uiPcVek6LbFRCxB2A)

Read more: https://www.massey.ac.nz/about/news/care-to-host-renowned-intellectual-for-activist-in-residence-programme/

#CAREConversations#MasseyUniversity #CAREMassey #Aotearoa #NewZealand #ThirdWorldFutures #GlobalSouthVoices#Anticolonialism #SustainableFutures #MasseyEvents #CAREActivistInResidence #TransformingTheSouth