CARE’s end-of-year address from Professor Mohan J Dutta, Dean’s Chair and Director of CARE via YouTube and Facebook.

Link to Facebook : https://www.facebook.com/CAREMassey/videos/891000409006859

Center for Culture-Centered Approach to Research and Evaluation

CARE’s end-of-year address from Professor Mohan J Dutta, Dean’s Chair and Director of CARE via YouTube and Facebook.

Link to Facebook : https://www.facebook.com/CAREMassey/videos/891000409006859

Check out CARE’s Māra Kai Project – Potatoe planting work continuing in Feilding

Presented by Selina Metuamate.

Facebook : https://www.facebook.com/CAREMassey/videos/6832398133475425

Join us for Professor Cherian George’s Public Talk at the Business Studies (Central) Building, Massey University, BSC B1.08 COMMS Lab. Or join us virtually via the Livestream on our social media platforms.

Facebook Page: https://www.facebook.com/CAREMassey/videos/310113508573077

CARE YouTube Channel: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rXwelom8Ac4

The norms and institutions of democracy and human rights are on the back foot around the world. They clearly need to be strengthened. This work has been disrupted and delayed not only by democracy’s opponents but also from within. There are recurring, divisive debates within liberal democracies concerning how much society should tolerate discriminatory speech. This talk searches for guideposts to navigate the contested terrain between free speech and social justice.

Cherian George is a professor of media studies at Hong Kong Baptist University’s School of Communication, and the director of its Centre for Media and Communication Research. His books include Hate Spin: The Manufacture of Religious Offence and its Threat to Democracy (2016); and Red Lines: Political Cartoons and the Struggle against Censorship (2021).

In Dr. Usman Afzali’s talk, “Long-term Effects of Far-Right Terrorism on Muslims in New Zealand,” the enduring consequences of far-right terrorism on the Muslim community in New Zealand are explored. Drawing upon a comprehensive array of scholarly papers and research from the New Zealand Attitudes and Values Study, the presentation investigates the complex dynamics between far-right violence, public attitudes, and the psychological well-being of Muslim minorities. It reveals how far-right terrorism can lead to national distress, affecting community cohesion and overall well-being. Public attitudes toward Muslims in New Zealand, especially following a terrorist attack, are examined, alongside the role of national identity, media influence, and the potential mitigating role of religion. Usman Afzali’s talk offers a comprehensive understanding of the multifaceted impact of far-right terrorism on Muslims in New Zealand, with implications for future research and policy considerations.

Dr. Usman Afzali is the principal investigator of the Muslim Diversity Study, currently working as a postdoctoral research fellow and lecturer at the University of Canterbury in Christchurch, New Zealand. The Muslim Diversity Study examines social attitudes and values of Muslims in New Zealand. Usman’s research interests encompass human flourishing, diversity in religious groups, cognitive psychology (specifically memory suppression), and contemplative neuroscience.

In the Muslim Diversity Study, he leads a team of 24 research assistants and actively collaborates with numerous partners within New Zealand. Additionally, he conducts research in cognitive psychology and neuroscience, and supervises graduate students at various levels (PhD, Masters, and Honours) since 2021. His teaching portfolio includes courses in statistics, research methods, cognitive psychology, and neuroscience.

Website: https://www.usmanafzali.com

Twitter: @UsmanAfzali

Join us online and celebrate the many accomplishments featured in the CARE documentary.

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/CAREMassey/videos/3699987516946842

https://www.massey.ac.nz/about/news/care-to-celebrate-10-year-anniversary-with-conference/

By Professor Mohan Dutta

Wednesday 30 August 2023

This opinion piece is the fourth of a five-part series on the intertwined webs of the far-right mobilised to attack communication and media studies pedagogy. This piece is written in solidarity with other communication and media studies academics, researchers, and practitioners who have been targeted by the far-right.

The far-right’s reactionary culture war, cooked up by the Trump-Bannon-Infowars-Fox infrastructure, materialised by extremist groups such as Proud Boys, and legitimised by the right-wing political machinery, has been and will continue to be vigorously resisted by academia.

The Cambridge Analytica whistleblower Christopher Wylie testified to the role of Bannon who, “saw cultural warfare as a means to create enduring change in American politics,” in shaping the strategy of gathering and leveraging information about 87 million Facebook users to drive Trump’s hate-based political campaign. Critical to the campaign was the targeting of African-American communities promoting voter disengagement, and collaborating with Russian intelligence services.

In three earlier essays crafted for this series, I have discussed exactly how the United States-far-right’s culture war is mimicked here in Aotearoa by the right-wing ecosystem working incessantly to pump out fear as an organising tool, as a photocopy of Bannon’s political strategy of deploying hate as a marketing tool. The manufacturing of a culture war as a strategic issue generates leverage, and more specifically votes, for right-wing political parties while simultaneously working to disenfranchise communities at the margins.

I have also outlined how these attacks are directed at silencing academic voices, particularly those working on issues of social justice, disinformation, and hate. Although academics are often the direct targets, the ultimate goal of the far-right is to silence the voices of the marginalised communities we partner with. The force of the attacks is particularly violent when directed at those of us in academia who engage in public scholarship.

In this piece, I will turn to strategies for countering the far-right and outline some of the powerful ways in which academics are resisting these targeted hate campaigns across the globe. Because the far-right’s cancel culture originates from the hate ecosystem linked with Donald Trump in the US, I will also draw upon US-based examples of academic resistance as instructive lessons.

Holding institutional processes accountable

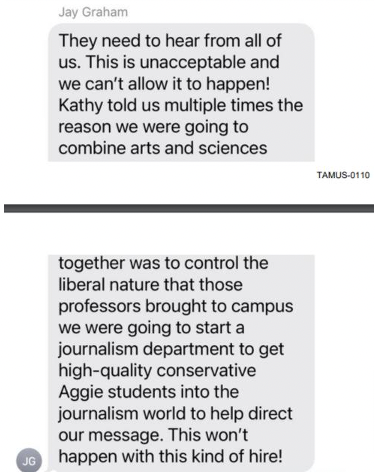

When brilliant Black journalism educator and former editor of the New York Times, Professor Kathleen McElroy, was appointed to lead the new journalism programme at Texas A&M University, the fringe far-right organised a campaign targeting her because of her history of promoting diversity. A conservative website seeded the campaign, building the “DEI (diversity, equity, and inclusion) hysteria” around the hiring of Professor McElroy.

The various pressures from these outside forces, mediated through the interference from the Regents, tampered with the university’s hiring process, resulting in Professor McElroy’s offer being altered, with multiple iterations walking back the tenured position initially offered.

The attacks were organised amidst the Republican Governor of Texas, Greg Abbott, signing a bill attacking DEI offices at public colleges, one among similar such concerted policies introduced by Republican lawmakers across the US. Note here that these fringe policies are built around the “Woke culture” and “Critical Race Theory (CRT)” frenzy that has been concocted by the far-right as political fodder, as a direct offshoot of Bannon’s political strategy of mobilising culture war as a campaign tool. As I have noted earlier, this hysteria around CRT is networked, traveling from the Trumpian ecosystem to the far-right ecosystem in Europe to Australia to Aotearoa.

The targeted campaign, materialised through the interference by the Regents and a timid administration lacking leadership, led to several institutional processes being violated.

A story published in the Texas Tribune first revealed these process violations and the change in the job offer to Professor McElroy. The story was picked up nationally, covered by major news media.

Responding to the events, the A&M Faculty Senate Executive Committee called for the Chancellor to meet with the full Faculty Senate to discuss political influence in faculty matters. The Faculty Senate met with then-President Katherine Banks, asked questions about the botched hiring, and initiated an investigation. An internal report examining the hiring process outlined several violations that took place during the appointment process.

Leaders of the Black Former Student Network wrote to the University System Chancellor John Sharp, saying:

“How this University treated this respected, honored, qualified, experienced, successful, and tenured fellow Aggie is unacceptable and would have been unthinkable yet for her race and gender… The fact that this University outwardly promotes very laudable principles in the Aggie Core Values, yet you don’t have the character nor the courage to follow these Core Values as the leader of this University reveals the deep chasm between your words and your actions.”

The fiasco led to the president’s resignation. The university separately settled with Professor McElroy for US$1 million and she stayed in her position at the University of Texas, Austin. The Texas A&M leadership released a statement, apologising “for the way her employment application was handled.”

In the backdrop of the organised campaigns of the far-right, coupled with the large-scale neoliberal transformations of universities that have foisted an overarching professional-managerial-consultant ideology, it is vital that academics across institutions globally work to strengthen faculty governance and oversight over decision-making processes, attending closely to the threats to academic freedom externally and internally, anticipating them, and responding to them pro-actively. In the US, elected bodies such as faculty senates carry out this powerful role of holding university managers accountable.

It is also critical that academics work alongside university leadership in developing institutional pedagogies around the threats posed by the far-right, mapping the pathways and sites of attacks, and developing and institutionalising strategies for responding.

For instance, one of the core strategies of the far-right is to pose as aggrieved students and concerned community members to carry out attacks targeting academics, often operating through fake social media accounts, anonymous email addresses, fake websites, sock puppet accounts, automated bots, troll farms, and instant messaging apps such as Telegram and WhatsApp. Email campaigns and university complaint portals are co-opted as tools for carrying out such swarm attacks, with influencers manufacturing grievance to mobilise such campaigns and directing followers to lodge complaints, working alongside automated bots and troll farms.

Educating staff in front-facing roles in sifting through and identifying spurious complaints, in detecting far-right disinformation-based narratives in the complaints, in raising the appropriate security alarms, and adequately responding to these narratives, is critical. Similarly, given the deployment of Official Information Act (OIA) requests to feed far-right propaganda, responding proactively to the propaganda and debunking it is critical. Also crucial is building the capacity of university managers in detecting potential instances of foreign interference and raising these through appropriate channels within the university. Such pedagogy needs to be built preventively across institutions, given the message swarms that far-right campaigns build, often funded by powerful political and economic interests, including right-wing think tanks, lobbies, astroturfs, and foundations.

Moreover, relevant state structures and institutional processes ought to be able to support universities with addressing the concerns raised, given the threats to institutional processes and democracy, and critically in the context of foreign interference into academic freedom through organised campaigns.

Building legal infrastructures

In the case presented above, Texas A&M reached a $1 million settlement with Professor Kathleen McElroy. The report released by the University General Counsel demonstrated egregious process violations. During the hiring process, university officials initially pushed for a delay until after the state legislative session adjourned, anticipating potential backlash from conservative lawmakers. Following complaints about her hiring raised by university regents, officials changed the terms of her contract.

As the process unfolded, with the terms of her contract changing significantly, Professor McElroy responded to the university, asking it to communicate through her lawyers.

In a similar high-profile case, Black journalist, Pulitzer-prize-winning author for the New York Times, and founder of the New York Time’s 1619 Project, a long-form journalism endeavour that documents the intertwined histories of slavery and the founding of the United States and was earlier labelled by Trump as “ideological poison,” Nikole Hannah-Jones, was initially offered a tenure track position by the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, that was then changed to a five-year contract.

Documenting the far-right backlash against her Pulitzer Prize-winning 1619 Project and targeting of critical race theory education, Hannah-Jones noted:

“Journalism schools reflect the same reality we see in the rest of the country…Why it’s especially troubling in journalism is that journalism is the firewall of our democracy. Journalism is what’s supposed to be exposing the way power is wielded. If that story is being filtered through an almost exclusively White lens, it’s not accurate. It’s not capable of helping us… understand the country we live in.”

She was supported by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) Legal Defense and Educational Fund in seeking justice through the legal framework. The university reportedly reached a settlement on the tenure dispute for less than $75,000.

The Hannah-Jones settlement is instructive because it includes several structural changes, proving the “correctness of critical race theory.” It outlines an inclusive search process for new employees in conjunction with the Office of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion; mental health counselling placed within the Multicultural Health Programme, complemented by the hiring of an additional trauma-informed therapist; and a $5,000 annual funding to the Provost’s Office to coordinate meetings and events sponsored by the Carolina Black Caucus working alongside UNC-Chapel Hill Vice Provost.

The far-right often directs its attacks on academics identifying with diverse marginalised positions. For instance, as with the examples of the organised campaigns targeting Professor McElroy and Hannah-Jones, the far-right interferences into university processes are racist, violating the fundamental human rights of academics having a protected characteristic. Building legal infrastructures such as the NAACP is critical to resisting the interference of the far-right into university processes.

Seeing and materialising connections

The organising structure of far-right hate produces its effect through the creation and amplification of fear. The mobilisation of fear results in swarms that target and attack academics and universities. These swarm-based campaigns have chilling effects, threatening the livelihoods and lives of academics.

The effects of these campaigns are amplified by the individualising processes that often place the onus of securing safety on individual actions to be taken by those being targeted. Consider the targeting of the University of Auckland academics, Associate Professor Siouxsie Wiles and Professor Shaun Hendy. The pair became the targets of attacks directed at their work explaining the science behind COVID-19. In a complaint to the Employment Relations Authority (ERA), they noted the university had failed its duty of care to them.

Attacks such as these call for the allocation of institutional resources to support academic freedom for public scholarship.

However, amidst the ongoing cuts to university funding globally including here in Aotearoa, finding the resources and allocating them to security (including digital security), legal support, mental health support, and media support is a challenge for leaders. Making provisions for security on funding applications and allocating funding resources for security to universities are two policy responses that can offer meaningful safeguards. The inclusion of community and social impact in the Performance-Based Research Fund (PBRF) ought to be combined with funding allocated to building safeguards around public-facing impactful scholarship. To advocate for such policy-based support, it is important that academics, unions, students, university leaders and policymakers work together.

Academic solidarities globally have been crucial to challenging the attacks by far-right campaigns. Letter writing campaigns and petitions have been vital in both responding to and developing preventive infrastructures for addressing the threats posed by far-right campaigns targeting individual academics, programmes of research, and academic departments.

Academic organising across institutions is a critical resource in mapping and responding to the interplays between institutional racism and far-right attacks. Disciplinary associations here can play central roles in responding to the organised attacks, developing both preventive measures as well as effective responses. Responding to the far-right attacks on communication education and scholarship, my disciplinary association, the National Communication Association (NCA), issued the following statement:

“As the preeminent scholarly society devoted to the study and teaching of Communication, NCA recognizes that professional educators, including Communication scholars and teachers, are best equipped to determine what is appropriate for their classrooms and curricula. Among other theories that plainly acknowledge the histories and impacts of race, Critical race theory (CRT) is foundational to effective communication teaching, learning, and practice. Simply stated: Educators cannot effectively teach communication without teaching about systemic racism and its impact on our institutions and policies, including teaching about CRT and its principles. Students cannot adequately learn about effective communication without exploring systemic racism in the history of the United States. To restrict freedoms to engage in the teaching of, and communication about, CRT and other theories which examine the historical and current impact of their principles is inconsistent with the principles of democracy. NCA opposes legislation that would censor content within the curriculum or classroom based on political disagreement or contrived controversy, particularly when such legislation curtails or prohibits teaching about the role of racism, sexism, and other forms of discrimination in the United States historically and today.”

The American Association of University Professors (AAUP) is an example of an organisational structure that is critical to safeguarding academic freedom in the US. Tracking the far-right campaign attacking Critical Race Theory in the form of bills passed across various states to Trump and the Make America Great Again (MAGA) campaign, noted the AAUP in its report:

“Language in these bills draws from Trump’s 2020 executive order on Combating Race and Sex Stereotypes and can be found in model legislation being pushed by MAGA lobbying arm Citizens for Renewing America. Both the executive order and model legislation are influenced by Russ Vought, Trump’s former budget director, who founded CRA. CRA is funded by the Conservative Partnership Institute, which is an effort by Trump allies to formalize extremist, far-right politics in the think tank sphere. Other organizations included under the CPI umbrella are the American Accountability Foundation, which attacks President Joe Biden’s Cabinet and judicial appointees, and America First Legal, which is run by former Trump speechwriter Stephen Miller and focuses on litigation that “oppose[s] the radical left’s anti-jobs, anti-freedom, anti-faith, anti-borders, anti-police, and anti-American crusade.” According to 2021 tax filings, CPI had an annual budget of $17.1 million, and revenues of $45.7 million.”

In the instance of the process lapses and racist institutional biases in the hiring of Hannah-Jones, the AAUP noted in the report titled, Governance, Academic Freedom, and Institutional Racism in the University of North Carolina System:

“In the case of retention of faculty members and administrative officers of color, while the individual motivations for their departures may be unclear, what is clear is that in one way or another a culture of exclusion, a lack of transparency and inclusion in decision-making, the chilling of academic freedom, discounting certain kinds of scholarship and teaching, and the constant threat of political interference have combined to fuel what some have called an “exodus” from the UNC system.”

Across global registers, it is critical to consider the possibilities for building academic associations committed to safeguarding scholarship. In Aotearoa for instance, such an organisation would among addressing other elements critical to academic freedom, track the funding flows of far-right hate and map potential foreign interference both discursively and materially, assess the risks to academia posed by disinformation campaigns, and respond robustly. Building partnerships with university leadership and relevant ministries are equally important in delineating the foreign interference at work (such as in the example of the “culture war” hysteria) and in developing preventive strategies to respond to it. Mobilising unions to address the threats to academic freedom is another potential avenue.

In addition, building solidarities with communities, civil society, and social movements is vital to resisting the forces of the far-right. The recognition that the attacks on universities are part of a broader pattern of attacks mobilised by the far-right ought to serve as the basis for crafting solidarities that witness and challenge the pernicious narratives and hate campaigns at societal levels. Connecting with activists and lending solidarity to those who are targeted by the far-right are critical to creating the broader infrastructure for resistance.

In the attacks I have experienced recently mobilised by the racist disinformation campaign launched by far-right networks here in Aotearoa, I have been humbled to be supported by collectives of activists, anchored in Māori leadership. When I discussed these targeted attacks with activists Tina Ngata and Sina Brown-Davis, they wrapped me up in a collective network of care. Within a few hours of our conversation, I had an email from The Manaaki Collective, offering a blanket of support, from security to legal assistance.

Te Tiriti and global leadership

The principles of Te Tiriti, foregrounding the values of participation, protection, and partnership offer powerful registers for resistance to white supremacy.

In Aotearoa, Māori have historically challenged racism and white supremacy in transformative ways, dismantling the hate politics of settler colonialism with the values of manaakitanga (caring about each other’s wellbeing, nurturing relationships, and engaging with one another) and whanaungatanga (forming, maintaining, and nurturing relationships and strengthening ties between kin and communities). Māori struggles for Te Tiriti justice have historically offered inspiration and hope to diverse struggles for social justice in Aotearoa and globally.

The Māori activists who have participated in the Activist-in-Residence programme at the Centre for Culture-Centered Approach to Research and Evaluation (CARE), Tame Iti, Teanau Tuiono, Dr Ihirangi Heke, Marise Lant, and Tina Ngata each outline the transformative power of connection as the organising basis for approaching relationships among human beings, in and between communities, and with land and the ecosystem. This meta-theory of “connection as organising” lies at the frontiers for pushing back against white supremacist hate.

The sustained resistance to white supremacy offered by Māori activists and communities position Aotearoa as a leader for global progressive struggles against white supremacy, and for interconnected struggles for climate justice, racial justice, Indigenous rights and migrant rights. Amidst the disenfranchising effects of white supremacy that seek to silence activist and academic voices, the inspiring work of The Manaaki Collective offers a global model for Indigenous leadership in securing safe spaces for organising “for racial, social, environmental, and Te Tiriti justice.”

As a university aspiring to be Te Tiriti-led, Te Kunenga ki Pūrehuroa Massey University has articulated the commitment to sustaining “a reputation for caring, inclusion and equity, and commitment to our people, our environment, and our places,” a commitment that speaks directly to the principles of Te Tiriti. I am proud of our university which puts forth a justice-based framework for academic freedom, in dialogue with the commitments of Te Tiriti, leading globally with a model that can sustain universities in safeguarding against disinformation campaigns by the far-right.

In conclusion

I wrap up this opinion piece by directly addressing the propaganda infrastructures of the far-right. Our message to the far-right reactionaries, in politics, in the media, on digital platforms, and in various hate formations, is loud and clear.

Backed by powerful economic forces, often hiding behind astroturfs, sock puppets, instant messaging apps, automated bots and fake websites, the far-right have launched propaganda campaigns that deliberately distort scholarship to suit the white supremacist agenda, confident that the targeted attacks can ban the teaching of critical concepts of social justice, and thus erase the powerful waves of voices emergent from the margins mobilising for transformational change.

And in spite of the economic power and political influence, replete with a digital infrastructure fuelling the dissemination of disinformation and hate, exponentially magnified by the globally linked hate networks, the far-right will continue to fail in securing hegemony.

The hate and divisive narratives that seed and propagate fear will fail because, as articulated forcefully by Martin Luther King, Jr, “the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice.”

The far-right threats to stalk us, get us fired, get us and our families deported, incarcerate us, rape us, dox our families on social hate platforms, and kill us will not silence the conviction of our scholarship, and the public impact this scholarship creates. We will continue to, along with the communities we partner with, carry out our research, generate empirical evidence that empowers communities in their struggles for justice, and transform the status quo.

Our public scholarship will continue to build registers for hope. Communities at the margins will continue to rise up, raise their voices and challenge the marginalising processes that seek to silence them.

In not cowering to the fear-based campaigns of the far-right, we will continue to be inspired by the words of Indigenous activists. In the words of activist Sina Brown-Davis, “Be unafraid, be powerful, we have everything to fight for and nothing to lose.”

Link to Massey News page: https://www.massey.ac.nz/about/news/opinion-this-is-how-we-fight-back-the-academes-resistance-to-the-far-rights-culture-war/

Professor Mohan Dutta is Dean’s Chair Professor of Communication. He is the Director of the Center for Culture-Centered Approach to Research and Evaluation (CARE), developing culturally-centered, community-based projects of social change, advocacy, and activism that articulate health as a human right. He is a member of the board of the International Communication Association.

Tuesday 25 July 2023 | By Professor Mohan Dutta

This opinion piece is part of a five-part series on the organised attack of the far right on communication and media studies pedagogy. This ecosystem has picked me as a sample case for all that is wrong with the discipline as a propaganda instrument of what it terms the “Left Woke Agenda.”

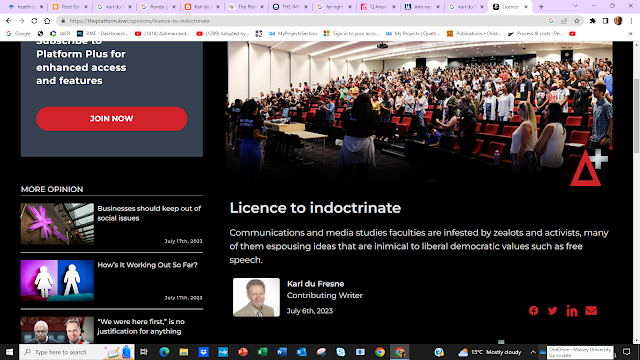

I had not heard the name Karl du Fresne. Apparently he’s a New Zealand journalist and blogger writing opinion pieces for The Platform – an outlet that has in the past circulated misinformation, hosted conspiracy theories, and participated in practices that might be considered unethical by journalistic standards.

Earlier this month, a journalist reached out to me on Twitter, sharing that du Fresne had written a hit piece for The Platform targeting me. They commiserated with me, sharing how they were also the target of an attack carried out by du Fresne earlier, directed at their employer and attacking their livelihood.

Fairly certain what the attack might look like, given the organised campaign by the far-right infrastructure targeting the academic freedom of scholars writing on issues of social justice (particularly racial and gender justice) and challenges around the Sustainable Development Goals (specifically gender equality, reduced inequality and climate change) across the globe (largely imported from the US-Infowars-Bannon-Trump-DeSantis-Tucker-Carlson hate machinery), I was curious to explore what a New Zealand take on this ecosystem would look like.

Unfortunately, what I found when I dug up the article was a shabby hit piece, replete with its uninspiring tediousness, parroting the far-right conspiracy themes from the Infowars-Trump-Bannon universe, and demonstrative of the organised attack on critical literacy directed at silencing the questioning of entrenched forms of power in society.

The article begins with the title “A blank canvas for stokers of the culture wars.” The framing of the title, portraying Aotearoa as a blank canvas, juxtaposed against the “stokers of culture wars” phrase gives away the racist ideology that drives the article.

To frame Aotearoa as a blank canvas for supposedly imported conspiracists like me (more on this later), du Fresne has to erase tangata whenua and the history of Māori activism against colonisation, racism, and white supremacy. The suggestion that stokers of culture wars are bringing in our “outsider” and therefore, impure ideologies of social justice in Aotearoa is racist, both in erasing long-held Māori leadership in struggles for justice here and globally, and in marking me, an ethnic migrant, as the wrong kind of migrant bringing in dangerous ideas that are corrupting Aotearoa by “stoking culture wars.”

Du Fresne also strategically obfuscates his own familial history as Tangata Tiriti, as manuhiri (visitor or guest) to this land.

As the article rolls on with its rhetorical fallacies, it seems obvious that what du Fresne seems to have an issue with is the fact that I teach and research at a University in Aotearoa. As a way to set up his attack, he targets the language that describes my programme of research on the Massey University website, suggesting the language used on the website is part of a radical conspiracy. He copies and pastes extensively from the website, stating that the description is “written in a dialect that most people would find almost incomprehensible.”

In democracies, it is the work of journalists to do the critical work of translating scholarship for the public. Of course, for bloggers such as du Fresne speaking to a right-wing conspiracy web while posing as a journalist, that would be too much work. Such work would entail doing research and learning, calling on critical pedagogy that is cultivated through rigorous journalism education, grounded in communication and media theory, participating in critical analyses of power (especially when reporting on social science and humanities scholarship), and drawing on critical engagement with questions of ethics in reporting.

Suggesting that making the language incomprehensible is purposeful and part of a larger conspiracy, du Fresne then goes on to write:

“Elite groups have always used their own coded jargon to project (and protect) their power, to enhance their aura of exclusivity and to impress the impressionable. The object is not to explain, as most language strives to do, but to obscure, presumably in the hope that no one will detect its phony portentousness. No one does this stuff better than neo-Marxist academics.”

Note here the slippery slope du Fresne embarks on, placing me as part of an elite group and implying that this group is part of a global conspiracy web to uphold and perpetuate power. This elite group does so through propaganda. In the conspiracy web that du Fresne cooks up, this elite group seeks to establish a Marxist global order, and it does so through the use of “coded jargon.”

His conspiracy draws directly from the misinformation-based discursive frames weaved by the Alt-Right. In this conspiracy web woven together by white supremacists, a global Communist conspiracy is being ushered in by Marxists, working alongside and/or being funded by the Chinese Communist Party, and intertwined with the agendas of the World Economic Forum, United Nations etcetera to secretly rule the world.

Critical to the propaganda woven by the far-right is mobilisation against knowledge and the university, and by extension, academics. Also worth noting is the specific targeting of social justice scholarship within the academe as an exemplar of the Neo-Marxist conspiracy.

For the far right, the framing of the teaching of theories of social justice in the academe as Marxist conspiracy works as a strategy for silencing the voices of Indigenous, Black, and migrants of colour communities. The white supremacist hegemony of the far-right sees the organising for justice from the margins as threatening to the status quo. Its conspiracy web therefore communicatively inverts materiality, inverting historic processes of racist marginalisation on their head to portray voices advocating for social justice as the elites occupying power.

Another communicative inversion performed here by du Fresne is the framing of social justice scholarship as an imported idea, all along inverting the direct replication of American far-right talking points in the article. The actual “culture wars” that are imported into Aotearoa are the far-right mobilisation of white supremacist cultural nationalism to attack academic freedom, in direct violation of the Education Act 1989, section 268 of the Education and Training Act 2020, and in continuity with the racist settler colonial infrastructure of Aotearoa.

Du Fresne then goes on – “The university system is awash with this gibberish – a fact that would be comical if we weren’t paying for it.”

Accountability to the taxpayer is one of the key resources in the mobilisation of the far-right. Designating themselves as gatekeepers, as representatives and advocates of the voices of the tax payer, far-right individuals and organisations launch their attacks on academic freedom by claiming that the research and teaching on questions of social justice are a waste of taxpayer money.

In portraying an entire body of scholarship (in this case, my research programme exploring the structural determinants of health inequalities and the communicative strategies for addressing these inequities) as gibberish, du Fresne demonstrates his lack of credibility as a journalist. He doesn’t really understand the scholarly process, much like other demagogues in this category who seek to find relevance through organised attacks based on heuristics.

The process of academic peer review, albeit with its multiple limitations, based on the participation in a rigorous peer review process by a community of scholars, establishes the credibility of knowledge. Within the academic community of experts, knowledge is contested, theories are offered and tested, and concepts subjected to empirical examination in an ongoing process of scholarly engagement. Any journalist writing about academic research programmes is expected to do the homework to understand how scholarly knowledge is produced, be ready to study the research programme, and equip oneself then to report on it. This process of engagement calls for deep reading, based on rigour. Of course, for bloggers such as du Fresne, this sort of painstaking and rigorous work is not conducive to generating superficial memes that speak to the conspiracy web.

Du Fresne cherry picks some examples from my research programme:

“The second conclusion we can reach on the basis of his profile is that Dutta is adept, like many of his ilk, at tapping into public funds – in this case from the AHRQ, which is part of the US Department of Health, and the National University of Singapore (NUS). The poor working schmucks whose taxes fund these institutions have no knowledge of, and even less control over, the radical agendas they enable.”

Once again, to comment upon specific research projects would call for actually educating oneself on the nuts and bolts of the research (not just google a webpage!). The US$1.5 million grant, funded by the Agency for HealthCare Research and Quality that he refers to, built on my research programme on the culture-centered approach, a framework I have developed over two decades of community engaged-health communication research that is recognised as a significant programme of research that has shaped the discipline, was designed to co-create a framework for disseminating the evidence-based comparative effectiveness research on heart health medications among the underserved African American communities in Lake and Marion Counties of the US. African American communities in the US experience disproportionate burdens of heart disease.

In this backdrop, the community-led culture-centered intervention, co-created through partnership with a range of African American organisations, and evaluated through a quasi-experimental community-based design, was effective in building community knowledge of heart health prevention and treatment. This intervention is an example of the sort of social impact generated by theory-driven scholarship. It is therefore both ironic and absolutely reflective of the disenfranchising agenda of white supremacy that du Fresne would target the AHRQ funded programme, framing it as being driven by a radical agenda (more on this in a follow-up piece).

You might ask, ‘Why does du Fresne pick on the AHRQ-funded intervention?’ For propagandists in the Alt-Right ecosystem, community health initiatives led by racially marginalised and historically oppressed communities is radical agenda. For these propagandists, reducing inequities in health outcomes is radical agenda. For the propaganda infrastructure of hate, historically marginalised communities having a voice in decision-making is radical agenda. Because the social order they so miss and would like to continue perpetuating is one where white supremacy rules, uncontested and unchallenged.

As I noted earlier, such propaganda in Aotearoa also has to erase the history of organising against health inequalities by Māori and the extensive body of Kaupapa Māori-based literature challenging these health inequalities to somehow make up the propaganda narrative that such ideas of health justice are imported ideas from the US, all the while parroting the US-based white supremacist agenda.

Professor Mohan Dutta is Dean’s Chair Professor of Communication. He is the Director of the Center for Culture-Centered Approach to Research and Evaluation (CARE), developing culturally-centered, community-based projects of social change, advocacy, and activism that articulate health as a human right. He is a member of the board of the International Communication Association.

Original article: source: http://culture-centered.blogspot.com/2023/07/the-far-rights-attack-on-communication.html by Prof. Mohan Dutta

Article source: https://www.massey.ac.nz/about/news/opinion-the-far-rights-attack-on-communication-and-media-studies/

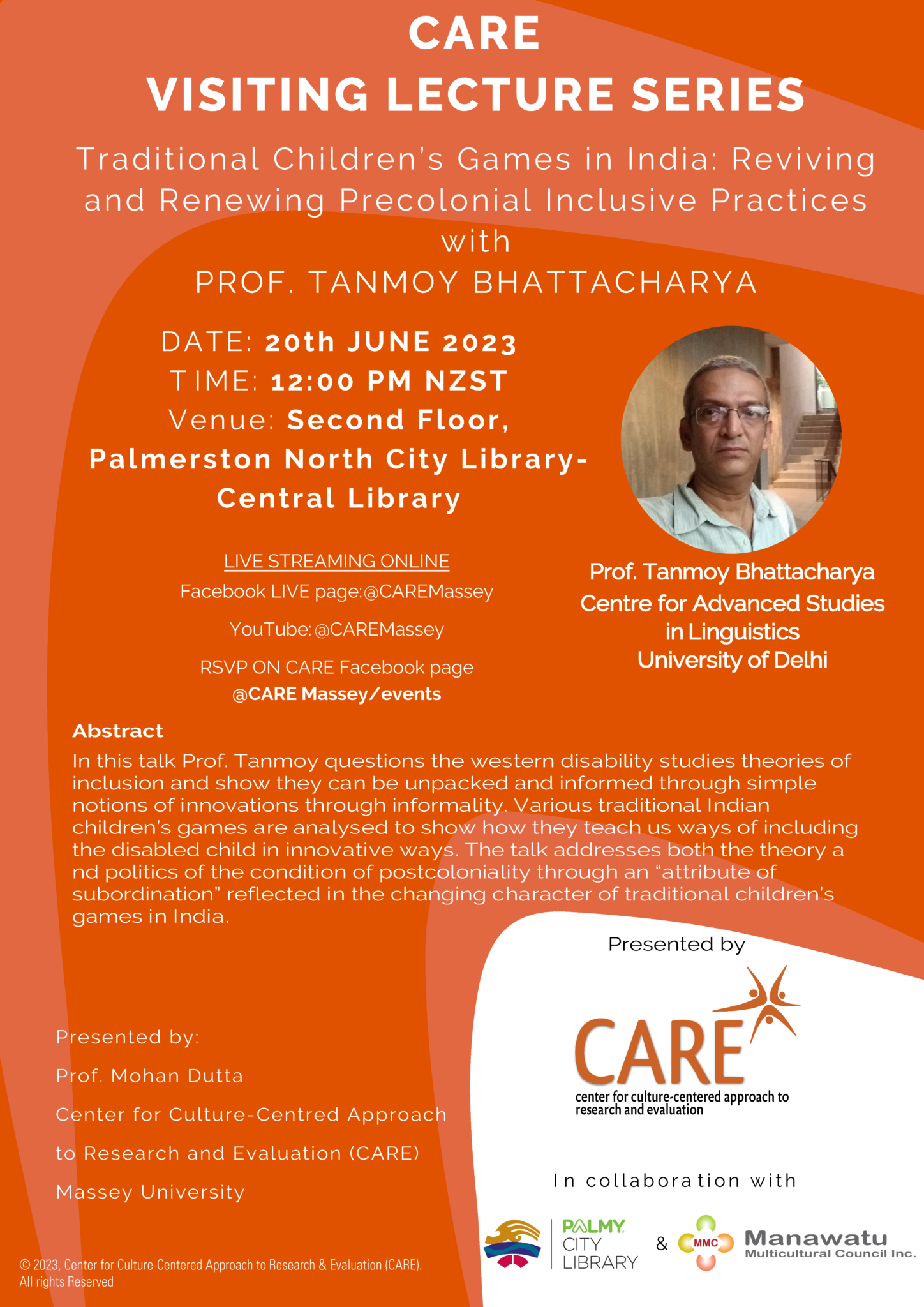

CARE proudly welcomes Prof. Tanmoy Bhattacharya, Head Department of Linguistics, University of Delhi, as CARE ‘s visiting academic for the month of June 2023.

CARE extends a warm invite to all to join Prof. Tanmoy Bhattacharya’s lecture on Traditional Children’s Games in India: Reviving and Renewing Precolonial Inclusive Practices scheduled on 20th June 2023 in Manawatu in collaboration with Palmerston North City Library & Manawatu Multicultural Council (MMC)

See event details below:

CARE VISITING LECTURE SERIES: Traditional Children’s Games in India: Reviving and Renewing Precolonial Inclusive Practices with Prof. Tanmoy Bhattacharya, University of Delhi

Talk Abstract

Traditional Children’s Games in India: Reviving and Renewing Precolonial Inclusive Practices

In this talk I question the western disability studies theories of inclusion and show they can be unpacked and informed through simple notions of innovations through informality. Various traditional Indian children’s games are analysed to show how they teach us ways of including the disabled child in innovative ways. The talk addresses both the theory and politics of the condition of postcoloniality through an “attribute of subordination” reflected in the changing character of traditional children’s games in India.

DATE: 20th JUNE 2023 | TIME: 12:00 PM NZST

Venue: Second Floor, Palmerston North City Library-Central Library

LIVE STREAMING ONLINE

Facebook LIVE page: @CAREMassey

Link: https://www.facebook.com/events/225044887004995

YouTube: @CAREMassey

Link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=i-U4ec_tpxw

RSVP ON CARE Facebook page : @CARE Massey/events

Link: https://www.facebook.com/events/225044887004995

#Aotearoa, #CareCCA, #CareMassey, #CareMasseyNZ, #CAREVisitingLectureSeries, #MasseyUni, #NewZealand

ICA 23 Toronto Preconference: Ethics of Critically Interrogating and Reconceptualizing Culture Ethics of Critically Interrogating and Reconceptualizing Culture

Organized by: Sudeshna Roy, Stephen F. Austin State University, US

Mohan Dutta, Massey University, New Zealand

We at CARE are delighted to support this keynote by Leena Manimekalai, Director of KAALI Filmmaker, poet, actor, and activist

The keynote “I make art to upwrite my cultural body” by Leena Manimekalai, Director of KAALI Filmmaker, poet, actor, and activist took place at the ICA pre conference on Thursday, 25 May 2023 after the screening of KAALI Film at Charbonnel Lounge in Elmsley Hall of University of St. Michael’s College, University of Toronto

This preconference is affiliated and sponsored by the following wonderful ICA Divisions and a fantastic research facility.

ICA: Intercultural Communication; Ethnicity and Race in Communication; Feminist Studies; Philosophy, Theory, and Critique

Research facilities: CARE: Center for Culture-Centered Approach to Research and Evaluation, Massey University, New Zealand

#ICA23 #ICAToronto #ICAPreConference #LeenaManimekalai #KAALI #CCA #CAREMassey #CARECCA #MasseyUni

CARE REPORT LAUNCH : EXPERIENCES WITH PLATFORM TECHNOLOGY FOR HOME SUPPORT WORKERS – THE NEED FOR A HUMAN CENTRED APPROACH

with panelists: JAN LOGIE, GREEN PARTY MP, and ANDREA FROMM, ADVISOR POLICY & STRATEGY | PSA

Presented by Dr. Leon Salter and Lia Vonk

Wednesday 10th May 2023 | 7.00 PM – 8.30 PM NZST

LIVE ON : Facebook @CAREMassey & on CARE YouTube channel

LIVE ON : Facebook @CAREMassey:https://www.facebook.com/events/936443157592800 & on CARE YouTube channel

YouTube URL: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_zbDe2s4YQE

Project Synopsis:

Platform technologies are being introduced by health providers in Aotearoa New Zealand to mediate relationships between care recipients and Home Support Workers (HSWs). They have been publicized by those providers as a potential solution to these challenges of health sector strain and ageing population. Much like in other sectors, platform technology is represented as offering autonomy for clients and empowerment for workers. This report critically investigates these claims and the broader impact of the introduction of platform technologies on the working lives of HSWs and their ability to provide dignified care for their clients. Drawing on 16 in-depth Zoom interviews and 1 focus group with Aotearoa-based support workers, we argue that technologies as currently used are exasperating pre-existing systemic failures, which have also been severely exposed by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Synopsis:

Platform technologies are being introduced by health providers in Aotearoa New Zealand to mediate relationships between care recipients and Home Support Workers (HSWs). They have been publicised by those providers as a potential solution to these challenges of health sector strain and ageing population. Much like in other sectors, platform technology is represented as offering autonomy for clients and empowerment for workers. This report critically investigates these claims and the broader impact of the introduction of platform technologies on the working lives of HSWs and their ability to provide dignified care for their clients. Drawing on 16 in-depth Zoom interviews and 1 focus group with Aotearoa-based support workers, we argue that technologies as currently used are exasperating pre-existing systemic failures, which have also been severely exposed by the COVID-19 pandemic.

About the Panelists:

Jan Logie is a Green Party MP based in the Mana Electorate. Jan worked for Women’s Refuge, the New Zealand University Students’ Association, the YWCA and numerous other social causes before entering Parliament in 2011. She served as the Parliamentary Under-Secretary to the Minister of Justice from 2017-2020 with a focus on sexual and domestic violence issues, and is Green Party spokesperson for Disability, ACC, Women, Te Tiriti o Waitangi, Public Services, Children, and Workplace Relations.

Dr. Andrea Fromm is a policy advisor with the NZ Public Service Association Te Pūkenga Here Tikanga Mahi (PSA). After receiving a PhD in political studies from the University of Otago, Andrea continued to focus on issues related to the decent work agenda. Her work has concentrated on labour markets and employment, working conditions and industrial relations and public and community services. Andrea worked with international organisations such as the ILO and Eurofound, as well as with Statistics NZ. Andrea started her career as a social worker.

Links:

Facebook @CAREMassey:https://www.facebook.com/events/936443157592800 & on CARE YouTube channel https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_zbDe2s4YQE