October 07, 2019 by Mohan J. Dutta

“No Singaporean Left Behind” (NSLB) campaign in Singapore

Between 2012 and 2018, the Center for Culture-Centered Approach to Research and Evaluation (CARE) was housed at the National University of Singapore. Based on the theoretical framework of the culture-centered approach (CCA) (Dutta, 2008), that conceptualizes communicative inequalities, inequalities in distribution of communicative opportunities, as intrinsically tied to structural inequalities, inequalities in the distribution of material resources, the Center co-created an array of communication interventions in partnership with communities at the margins in Singapore, India, Bangladesh, China, Philippines, Malaysia, and Indonesia. Culture-centered interventions build voice infrastructures for the margins based on the theoretical argument that the erasure of voice infrastructures forms the basis of marginalization.

The impact of these interventions are evident in the creation of material resources that serve the margins, from creating food distribution programs run by the poor, to building locally-anchored sustainable agricultural systems, to developing health interventions, to designing community-based health resources, to co-creating democratic frameworks for building infrastructures for clean drinking water, to co-creating cultural infrastructures for health and wellbeing.

Video Exhibit 1: The Piyalgeria Community project, building community cultural resources for wellbeing.

In Singapore, interventions resulted in foregrounding a wide range of issues based on community-anchored research, including the challenges experienced by foreign domestic workers with securing access to decent working conditions, food insecurity experienced by migrant construction workers, and the everyday stigmas experienced by low-income households in Singapore.

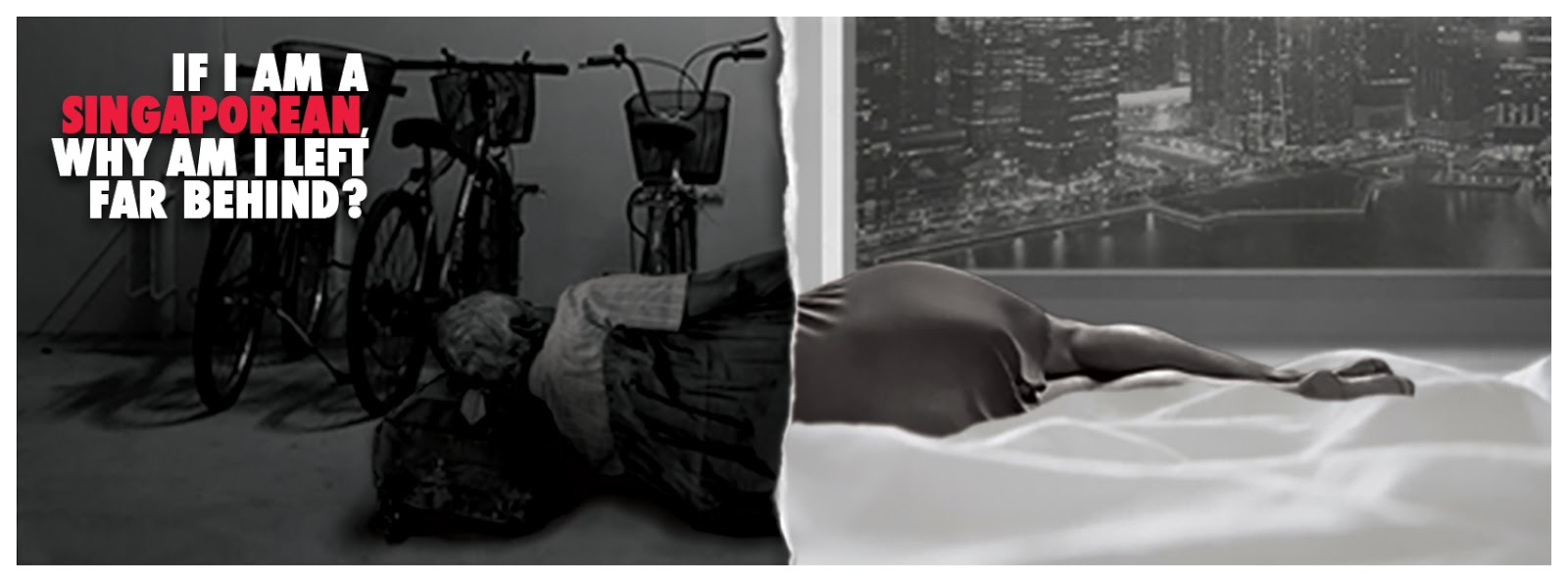

Advocacy campaigns, such as the “Respect our Rights” campaign and the “No Singaporeans Left Behind” campaign, were created by advisory groups of community members, who shaped and anchored the research undertaken by the CARE team. The voices of the margins in Singapore, emerging into our co-constructive knowledge production offer theoretical insights for instance into the communicative inequalities experienced amidst negotiations of hunger by low income households, the stigmatization experienced by domestic workers, and the ideologies that reify inequalities.

Video Exhibit 2: The campaign video of the “No Singaporeans Left Behind” intervention. This intervention played a key role in opening the conversation on poverty and inequality in Singapore, anchored in the voices of the poor.

The right to voice of the margins, when exercised through culture-centered interventions, transforms the discursive domain. For instance, the voices of the poor in Singapore foreground hunger as an everyday experience, disrupting discursive erasures of experiences of poverty.

The rigour of culture-centered research was/is deeply embedded in the ownership of the research process by those at the margins, thus shaping the research design, data gathering, and data analysis through the active participation of community members. Voices of communities at the margins come to own the spaces of knowledge production through the foregrounding of their everyday lived experiences as the anchors to the research journey. Based on the idea that marginalization is constituted in the erasure of voice, culture-centered interventions explore the sites that silence the voices of the margins and address the power inequalities that are built into the processes of silencing at these sites. The communicative right to voice transforms the production of knowledge through the ownership of knowledge production in the hands of those at the margins, contributing to the democratization of knowledge.

A culture-centered intervention that results typically from over three years of community-immersed scholarship calls for extensive labour, resulting in empirical insights that are richly embedded in the rhythms of community life. Typically, the research team collaboratively puts in more than 500 hours of fieldwork, “learning to learn from below” through solidarity-based partnerships (Spivak, 2013).

These communication interventions thus developed are anchored in theoretical questions about the nature of power and control in constituting erasure of the margins, and the role of communicative resources in creating infrastructures for listening to the voices of the margins. Theoretical insights about the role of communication infrastructures emerge from the practical work of “building” culturally-situated spaces of community voice and empowerment. In other words, the everyday work of participating in practical community partnerships for voice infrastructures is central to the generation of theoretical insights on social change communication.

The various culture-centered projects carried out in Singapore invited different forms of responses from the range of organizations and structures we interfaced with. For instance, the work of the “Respect our Rights” campaign, created by foreign domestic workers, offered discursive registers for dialoguing and collaborating with the Ministry of Manpower (MOM). The dialogic process resulted in the presence of the Ministry in conversations which were anchored in the voices of domestic workers. This also contributed to an overall sense of self and collective efficacy among the domestic workers who participated in our advisory groups.

CARE’s project with low-income families generated a different set of responses from the system, with arms of the the structure asking questions such as, “Why is CARE running social change projects?” and “Why did the Center host a conference on social change communication?” In response to these questions, I referred to the intertwined nature of theory and practice in social change communication, articulating the ways in which “the doing of social change work” is a part of the methodology of generating theoretical insights about social change communication.

Moreover, in Singapore, CARE engaged with activists such as Jolovan Wham, Braema Mathi, Vanessa Ho, and Sherry Sherqueshaa to generate dialogic anchors to theory building (in multiple instances, I was interrogated regarding my relationship with the activists and regarding the nature of the work the activists were doing). The contribution to the scholarship of social change communication made by these activists is immense, with their practical knowledge forming the basis for shaping how we come to understand the different elements of social change communication. Consider that exactly a year before the voice of Monica Baey drew attention to sexual harassment at NUS, Ms. Braema Mathi worked as a research partner at CARE, producing a white paper on strategies for addressing sexual violence specifically on University campuses. The many practical recommendations made in the white paper later came to be adopted by higher learning institutions in the aftermath of the saga.

Engaging activists in conversations on social change communication generates tremendous impact in terms of creating anchors for positive social change. The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) identify reduced inequality, gender equality, zero hunger, and no poverty as some of the key areas of impact. Activists, as citizens working directly with the marginalized, bring a wealth of knowledge that directly contributes to the generation of social impact. Universities can play vital roles in generating such social impact, by not turning away from activists, but instead by seeking communicative spaces for dialogic conversations, by collaboratively developing strategies for addressing the SDGs. In the context of Singapore, each of the activists we collaborated with shaped our theoretical insights about communicative processes for listening to the voices of the margins.

Video Exhibit 3: The panel on academic-activist collaborations hosted by CARE under the “Communicating Social Change” conference.

The activist-in-residence program run by CARE has had the delight of hosting activists from various parts of the globe, including the Singaporean activists Braema Mathi, James Gomez, and Sangeetha Thanapal. Each of these activists have participated in series of dialogues with me, as well as co-written a white paper. The white paper reflects one such avenue of dialogic knowledge generation through academic-activist partnerships.

The nature of practical knowledge thus generated is also theoretically rich, attentive to nuances and the sociocultural context of change. For instance, the white paper written with the veteran New Zealand activist and former Green Member of Parliament, Dr. Sue Bradford, explores the strategies for academic-activist partnerships in servings the needs of those at the margins. Similarly, the white paper generated by the collaboration with the refugee rights activist Dr. Murdoch Stephens generated vital conversations on the voice infrastructures for refugees in New Zealand. Sadly, I have witnessed instances of activists being used for data gathering purposes by academics, without being given due credit and without being acknowledged for their roles in the generation of knowledge. In one such instance, a Singapore activist had designed the questionnaire, conducted the translations, recorded the data, only to be then erased from the emerging publications. The activist-in-residence program at CARE is transformative precisely because it recognizes and centers the labour and contributions to knowledge made by activists.

The Lewinian maxim, “there is nothing as practical as a good theory” forms the basis of the theory-practice linkage in the study of social change communication, and more broadly, in a larger part of the communication discipline. As an Applied Communication scholar, I have come to recognize that the rigour of theorizing is intrinsically connected to practice. Sitting at a distance in the ivory tower largely limits what I am able to see and how I see a phenomenon. The many hours of my everyday work I spend in the field, collaborating with community members, having conversations, and producing change materials, shape my theoretical understandings of the social change communication process.

To theorize a social change communication phenomenon well, one has to know intimately what it means to participate in that phenomenon. The flagship National Communication Association Journal of Applied Communication Research explicitly calls for a section on application that engages directly with the question of impact. The bodies of scholarship on “Public Communication Campaigns” and “Policy Communication” are built on theorizing immersed in practical work. As one of the largest areas of Health Communication, Communication Campaigns draw on lessons learned from the design, implementation, and evaluation of Communication Campaigns. Singapore’s Ministry of Health for instance has funded many such campaigns that have drawn in academics in carrying out formative research, developing campaign design, and carrying out evaluation. Similarly, Singapore academics consistently collaborate with various state agencies in designing and evaluating programs. Such work should be recognized as it offers incredible value to generating social impact through scholarship, in turn impacting the very nature of scholarship through empirically-informed theorizing. I am sure the Yale President, Professor Peter Salovey, a close ally of Health Communication, is all too familiar with this strand of scholarship.

The recent saga of the cancellation of a course on “Dialogue and Dissent” at Yale-NUS College (YNC) unfortunately sets up a theory-practice divide that is spurious. It does so to limit the academic space, keeping out voices of difference from the academe. In the ensuing conversations about the cancelled course, the different accounts offered by the renowned playwright-poet Alfian Saat, who had been invited to teach the course, and the YNC leadership points to the game of communicative inversions. References to lack of rigour and unresponsiveness to feedback are deployed by the YNC leadership, and later by a Yale report crafted by the former YNC President, Pericles Lewis, are contested by Mr. Alfian Saat. Challenging the report and the claims made by YNC, Mr. Saat points out that he had indeed responded to the call for changes and the issue of rigour was never pointed out to him. The news of the event has triggered what appears to be a targeted campaign attacking the legitimacy and patriotism of the playwright-poet. Ironically, an elite North American institution that vociferously lays claims to liberal principles, is mired up in the vilification campaign, having carried out an investigation that itself appears biased (with the former YNC President charged to carry the investigation).

In the latest round of attacks on Mr. Saat (including selectively reading his poetry to project him as unpatriotic), the Minister of Education in Singapore puts in official state script the state’s reading of academic freedom. In his speech to the Parliament, the Minister of Education, Mr. Ong Ye Kung, states the following:

“Our educational institutions should not be misused as platforms for partisan politics. Professor Rajeev S. Patke, director of YNC’s humanities division, put it very well. In an e-mail to the College leadership, he wrote: “To study is distinct from to practise: to study ‘contemporary resistance’ or ‘contemporary violence’ or ‘contemporary prejudice’ is not the same as to practise resistance or violence or prejudice. We have to ensure that in our educational institutions, academic study does not get confused or compromised by courses of action and intervention which belong to the realm of individual choice.” In Singapore’s democracy, there are many avenues for political parties and activists to champion their causes, and for people to make their choices and exercise their political rights. Educational institutions, and especially the formal curriculum, are not the platforms to do this.”

That engagement with activists, particularly activists that are seen as challenging Singapore’s authoritarian status quo, is partisan politics serves as the basis for the exclusion. The framing of the activists Jolovan Wham, Seelan Palay, Kirsten Han, and P J Thum (note here that Dr. Thum had nothing to do with the Yale-NUS offering) as participating in political resistance serves as the basis for their exclusion from educational institutions. Worth noting here is the Minister’s selective use of the term partisan, erasing the very partisan worldview that shapes his reading of resistance to authoritarianism as partisan. Moreover, the depiction of Wham and Palay as “convicted of public order-related offences” obfuscates the underlying principles of freedom of expression and assembly that guide their performances, which led to the convictions. Note here, and Minister Ong is clear, some activists, not all activists, are excluded. Which of these activists, the so-called “personalities” that are going to be excluded are going to be determined by Mr. Ong, the state, and by extension, the ruling party.

Mr. Ong then draws on an email written by the YNC’s director of the humanities program, Mr. Rajeev Patke. A literary scholar, Mr. Patke is quoted as stating that academic study should not be confused with action. Mr. Patke conveniently erases the long tradition of the engaged humanities and social sciences, and omits the robust bodies of scholarship emerging from action research, community-based participatory research, participatory action research, and engaged scholarship, which are all deeply embedded in the worlds of practice. His opinion captured in this excerpt is misinformed at best, and strategically misleading at worst.

That the humanities at YNC are headed by someone who, writing in 2019, espouses a worldview that is entirely unaware of entire bodies of scholarship of practice-based scholarship raises concerns about the so-called liberal commitments of the YNC, particularly within the broader context of academic freedom in Singapore. Mr. Patke’s statement then is served as the basis for the minister to academic freedom, noting that Singapore’s educational institution’s should not be used as platforms for championing causes.

Also absent from the Minister’s conversation is the interrogation of the very partisan nature of what constitutes the mainstream curriculum in autonomous institutions in Singapore. Is it partisan for instance to teach to hegemonic articulations of assembly and expression that put forth cultural context as the basis for authoritarian practices? Is it partisan to teach specific versions of authoritarianism as normative, under the umbrella of “Singapore Studies,” with uncritical references to context? Is it then partisan for Ministers and bureaucrats from the Ministry to represent views about hegemonic practices in university settings? What is the balance to these hegemonic formations in Singapore, where authoritarian norms limit the forms of participation in everyday life? What are the erasures that are actively cultivated when the voices of Jolovan Wham and Seelan Palay are actively tarnished and erased, under the naturalized language of conviction? More fundamentally, what does it even mean to house a liberal arts program in Singapore if the hegemonic voices of an authoritarian regime deploy techniques of othering to silence the voices that call for greater freedoms of assembly and speech?

As I have noted elsewhere, academic freedom is a universal principle, not dependent on context. You can’t have it both ways, claiming commitment to academic freedom and then using context as a strategic tool to attack academic freedom.

In Minister Ong Ye Kung’s version of academic freedom, the limits to freedom are shaped by context. The Minister of Education draws on the ordinary citizen to discuss who and what is going to be allowed/not allowed on University campuses in Singapore.

“I much prefer the test of an ordinary Singaporean exercising his common sense. He would readily conclude that taking into consideration all the elements and all the personalities involved, this is a programme that was filled with motives and objectives other than learning and education. And MOE’s stand is that we cannot allow such activities in our schools or IHLs. Political conscientisation is not the taxpayer’s idea of what education means.”

Note the fallacies in Mr. Ong’s ordinary common sense test. Political conscientisation earlier described accurately as “aimed at making people conscious of the oppression in their lives, so that they will take action against these oppressive elements,” is then inaccurately ascribed motives and objectives other than learning and education. By Mr. Ong’s own correct reading, the very purpose of conscientisation is to educate, to make one critically aware of their circumstances and the forces of power they are situated amidst. So what then is it about conscientisation that makes it unacceptable in Ong Ye Kung’s Singapore? What does the Minister worry would happen if the oppressed become aware of their oppression and of the forces underlying the oppression? The imagined taxpayer’s idea of what education means then is used to exclude particular forms of education such as “conscientisation” from Singapore’s educational settings.

Having explicitly made this move to exclude, Mr. Ong then goes back to stating “MOE values academic freedom, so do our AUs.” This is a classic example of communicative inversion. Elsewhere, Mr. Ong’s speech is rife with communicative inversions, equating activists advocating for freedom with Jihadists and Nazis. Communicative inversions referring to jihadists and Nazis are drawn upon to stigmatize activists advocating for freedom of expression, freedom of assembly, and democracy, and to legitimize their exclusion as normative.

Coming back to my introductory question, are culture-centered projects viable in Singapore, I am inclined to answer in the negative. Under the current conditions, with explicit references to misinformed divides drawn up between theory and practice to serve partisan purposes, I don’t see how culture-centered projects can be implemented in Singapore, especially within the structures of Singapore institutions. One might surmise that some Ministers in the ruling establishment might see the culture-centered process as “conscientization.”

By the same logic, any applied scholarship where the act of doing is deeply tied to theorizing, would come under scrutiny. Unless of course, the theory-application binary is strategically drawn upon to reproduce state control over what is taught and what is practiced in the Universities in Singapore.

References

Dutta, M. J. (2008). Communicating health: A culture-centered approach. Polity.

Spivak, G. (2013). The Spivak Reader: Selected Works of Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak. Routledge.